The counterpane in Cowper’s bedroom is made of cotton, and was finished in about 1790. It was made for him by one of his female admirers, a Mrs King of Pertenhall, near Kimbolton, Bedfordshire. The backcloth is of ‘tabby weave’ (a simple ‘over and under’ weave) and is undyed. To it are applied various cut-out motifs and scrolling cartouches which are also woven from natural cotton but overprinted with blocks to create their colour. The motifs are organic – mostly scrolling flowers, petals and leaves – and, within the central large cartouche, three birds, a butterfly, two small budding flowers, a strange winged beast (probably another bird), another flying insect and a dog.

How was it made?

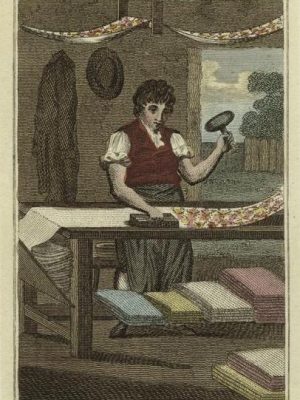

The counterpane is hand-sewn throughout. The motifs are applied as patches and, if you look closely, you may be able to see that these are attached with a knotted thread. The fringe that runs around each edge is also made from knotted thread. Knotting was considered a polite craft and was much practised by elegant society of the mid-eighteenth century: ladies would carry around their knotting in small pouches, taking it with them to the theatre or other smaller social gatherings where they could demonstrate their composure as well as their useful employment by knotting throughout the entertainment. So it was regarded as a refined occupation and Cowper refers in some of his letters to the fact that Mrs Unwin (his companion at Orchard Side) and the ‘ladies’ were busy knotting of an evening as he reads to them.

Knotting

Knotting takes some considerable skill. The knots themselves are straightforward overhand knots (here made of cotton yarn) but they need to be placed evenly, and only a millimetre or so apart. This regularity is really quite hard to achieve, but if you look closely at our example, you can see that Mrs King has managed it very well. A large shuttle is used to carry and manipulate the thread. It might be made of ivory or wood and is boat-shaped like tatting shuttles, but about double the size. Indeed, knotting is said to be the precursor to the double-knot involved in tatting. The hours, days, weeks that Mrs King must have spent producing enough knotted thread to attach the motifs AND to make the looped fringe running round the whole edge of the bedspread are impressive to say the least.

Although knotting and tatting work might look superficially similar – just a row of closely spaced knots – the knots are made and function differently. The single over-hand knot produced by the knotter will not move – and so must be very carefully positioned when tightened. The two half-stitches which form the full tatting knot, on the other hand, involve quite complex looping manoeuvres, after which the final ‘knot’ will slide into position.

The finished appliquéd front is attached to another plain, and naturally-coloured, cotton back-cloth; this material hides the sewing stitches involved in the appliqué work and provides a smooth surface suitable for a bedspread.

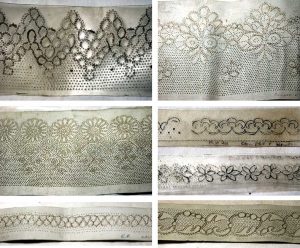

The printed motifs

If you look at the leaves you might agree it is quite hard to see two print patterns that are the same. Some of them have very simple designs – spots for example – others show rather more complex forms such as tiny flowers or sprigs. They have been cut into their leaf shapes from specially prepared cotton – cotton that could be over-printed with the natural dyes you see here. The other shapes have been cut out from similarly printed cloth so as to represent a dog, the flower, the butterfly and so on. Clearly Mrs King was eager to feature objects from the natural world, objects that Cowper was particularly fond of and wrote about so often, and so eloquently.

Because the fragments used to form the various appliquéd objects are so small and vary in printed design, it is tempting to suggest that they were taken from a pattern book of the later eighteenth century when printed calicos were really wowing the Western market and purchasers would be keen to know what was available and ‘the latest’. Earlier in the century, the popularity of Indian printed cottons had threatened the English and European wool and silk trades severely and their import was prohibited. But once the Lancashire cotton trade took off in the mid-eighteenth century, the balance of trade in such goods between the UK and India became more favourable, and by 1774 the import ban was lifted and there arose a huge demand for cotton prints. Also, the taste for an Exotic and Indian look could now be met by block-printed products, often more cheaply produced (usually in France) than the hand-painted specialities – the true calicos – from India itself.

To find out more: Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 DATS (Dress and Textiles Specialists) in partnership with the V&A and 18th century printed cotton at Jane Austen’s World

Who was Mrs King?

Mrs Margaret King (1735-1793) was the daughter of a vicar from Saling, Essex. In 1752 she married the Reverend John King, who had been a fellow student of Cowper’s at Westminster School. So Mrs King had some familiarity with Cowper through her husband, who was also a friend of his brother John. Perhaps due to these links and because she knew and admired Cowper’s published work Mrs King seems to have felt it acceptable to introduce herself to Cowper in writing. In early 1787 we learn from a letter written to a friend by a rather surprised-sounding Cowper (who by then had moved from Olney and was living at Weston Underwood) that:

I have lately had a letter from a lady unknown to me tho’ she tells me she was intimate with my brother.

It’s worth reflecting that Cowper is a man of considerable public standing by now. He is a much-respected poet. Olney Hymns, John Gilpin and The Task are all published and have been widely acclaimed. But his fame does not seem to have daunted Mrs King, and it is interesting to see how their correspondence and friendship develops.

In his first letter back to her, he politely thanks her for saying she admires his work, then goes on, basically, to quiz her as to who on earth she is! He writes:

Since the receipt of your obliging letter, I have naturally had recourse to my recollection to try if it would furnish me with the name that I find at the bottom of it…Ascribe it Madam not to an impertinent curiosity, but to a desire of better acquaintance with you, if I take the liberty to ask (since Ladies’ names at least are changeable) whether yours was at that time the same as now.

In a later letter Cowper says he’d like, through their correspondence, for them

…to know as much of each other as we can, and that as soon as possible…

And so things progress, with Cowper telling Mrs King about such personal things as his early life, his bouts of melancholy and his religious faith. All this without a meeting.

Mrs King’s portrait

Then, in August of 1788, Cowper becomes more playful. He chooses to write up an imaginary pen portrait of Mrs. King – a lady he has yet to see – and send this to her in his letter. She must previously have confessed to living a rather sedentary life as Cowper has some polite fun with this information in his response. The picture he says he has formed of her in his own mind runs thus:

…Your height I conceive to be about 5 feet 5 inches, which though it would make a short man is yet height enough for a woman. If you insist on an inch or two more, I have no objection. You are not very fat, but somewhat inclined to be fat, and unless you allow yourself a little more air and exercise will incur some danger of exceeding in your dimensions before you die. Let me, therefore, once more recommend to you to walk a little more, at least in your garden, and to amuse yourself occasionally with pulling up here and there a weed; for it will be an inconvenience to you to be much fatter than you are at a time of life when your strength will be naturally on the decline. I have given you a fair complexion, a slight tinge of rose in your cheeks, dark brown hair, and if the fashion would have you leave to show it, an open and well-formed forehead. To all this I add a pair of eyes not quite black but nearly approaching to that hue, and very animated. I have not absolutely determined on the shape of your nose or the form of your mouth, but should you tell me that I have in other respects drawn a tolerable likeness, have no doubt but that I can describe them too.

Mrs King was evidently not at all put out by being thus imagined; indeed she seemed to redouble her attentions to Cowper. For in September he thanks her for the many presents she has just sent to Mrs Unwin and himself. These include a pocket case for needles, scissors and thread (‘a hussif’ as Cowper calls it), a fire-screen, and a toothpick case, as well as apples and cake. Quite a list!

It appears that Cowper was uncannily accurate in the mental picture he had formed of her. The following letter, from one who knew her at this time, bears out his intuition to a remarkable degree. How he would have loved, when a Westminster schoolboy himself, to receive ‘ghostly counsel’ from this attractive motherly figure!

Mrs King in her reply would not allow that the poet was correct in this conjectural portrait. It appears however that his sketch was not far from the truth…There is a portrait of her in oil at Pertenhall parsonage, which represents her as a pretty rosy-faced girl. When I knew her about the year 1788, she was certainly very much en bon point, – a comely dame to look at; with a full open countenance, of a benevolent cheerful expression, very fair, and retaining the traces of youthful beauty; nor had the rose entirely forsaken her face. Being then a Westminster schoolboy, I used to spend the summer holidays with Mr and Mrs King at Pertenhall parsonage. As she was my godmother, she was accustomed to hear me repeat the catechism, and give me ghostly counsel, which was sweetened and impressed by a liberal store of plum cake, and other good things with which her closet abounded.

Rev. John King Martyn to the Rev. G.C.Gorham, 13 November 1835,

included in Robert Southey’s 1836 edition of Cowper’s Life and Works.

I think we glimpse in Cowper’s pen portrait something of the charming way he had with ladies – and, through her gifts in response to it, how successful he was. Mrs King must have felt flattered to have this teasingly personal attention from The Great Cowper. And she was just one of many ladies who were devoted to him and sought his company.

Throughout 1789, we learn of more presents (including plum cake!) flowing to Cowper from his generous and hard-working admirer. For example, he received:

a basket addressed to me from my yet unseen friend Mrs. King; it contained two pairs of bottle stands, her own manufacture, a knitting-bag and a piece of plum cake. The time seems approaching when that good lady and we are to be better acquainted, and all these douceurs announce it.

Typically, she liked to send him home-made things:

a basket containing…good things…chiefly preserves and pastry.

The gift of the counterpane

This was sent to Cowper in 1790. It prompted the following poem by way of a ‘Thank You’.

TO MRS KING

ON HER KIND PRESENT TO THE AUTHOR:

A PATCH-WORK COUNTERPANE OF HER OWN MAKING

The bard if e’er he feel at all,

Must sure be quicken’d by a call

Both on his heart and head,

To pay with tuneful thanks the care,

And kindness of a Lady fair,

Who deigns to deck his bed.

A bed like this, in ancient time,

On Ida’s barren top sublime,

(As Homer’s Epic shows)

Composed of the sweetest vernal flow’rs,

Without the aid of sun or show’rs,

For Jove and Juno rose.

Less beautiful, however gay,

Is that, which in the scorching day,

Receives the weary swain:

Who, laying his long scythe aside,

Sleeps on some bank with daisies pied,

‘Till roused to toil again.

What labours of the loom I see!

Looms numberless have groaned for me!

Should ev’ry maiden come

To scramble for the patch, that bears

The impress of the robe she wears,

The bell would toll for some.

And O! what havoc would ensue!

This bright display of evr’y hue

All in a moment fled!

As if a storm should strip the bow’rs

Of all their tendrils, leaves and flow’rs,

Each pocketing a shred.

Thanks then to ev’ry gentle Fair

Who will not come to pick me bare

As bird of borrow’d feather,

And thanks to one, above them all

The gentle Fair of Pertenhall,

Who put THE WHOLE TOGETHER!.

At this time they had met but once and Mrs King died in 1793, perhaps without their meeting again.

Conclusions – what have we learned?

We learn a little of Cowper’s way with women. We also see, through Mrs King’s eyes, a man she knew to love nature – birds, plants, a dog (perhaps his own spaniel Beau) – as represented in the patched work. And, through her choice of a hand-crafted gift, a man she also knew to be at ease in a domesticated setting and to value what might be called ‘women’s work’. In The Task Cowper gives us a taste of an evening in Olney:

But here the needle plies its busy task,

The pattern grows, the well-depicted flow’r

Wrought patiently into the snowy lawn

Unfolds its bosom: buds, and leaves and sprigs,

And curling tendrils, gracefully disposed,

Follow the nimble finger of the fair;

A wreath that cannot fade, of flow’rs that blow

With most success when all besides decay.

The Task, IV:The Winter Evening,150-7

It is perhaps not too fanciful to think that Mrs King, in designing and working her counterpane, took this description from Cowper’s poem and set about realising it with her own needle and thread.

Update: conservation work on the counterpane

The bedspread has become damaged over time. There are some bad stains as well as fading. The museum began by ‘making good’ the loose appliqué and controlling the amount of light that falls on the fabric. Further conservation work is planned by an expert textile conservator but the museum has no dates for this work as yet.

Take a Peek Inside Cowper’s Bedroom