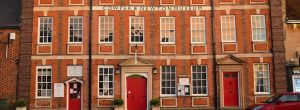

Lace Making at the Cowper & Newton Museum

This is not an exhaustive account of lace, of lace-making techniques, or of the industry in the Eastern Counties, but just an introduction. We hope you find it interesting and useful. Our extensive lace collection is on display at the Museum within The Lacemakers Room.

The Eastern Counties in this context are Buckinghamshire (Bucks: Olney is in Bucks), Bedfordshire (Beds) and Northamptonshire (Northants).

Lace is still being made in Olney today – but purely for pleasure. See The Olney Lace Circle to find out more or for Hanslope Lace visit the Hanslope Village website.

If you are interested in the history of lace and lace-making, you might like to look here at a local walk around Olney on the Olney and District Historical Society website

The Lace Industry

Lace was probably made in the Eastern Counties (Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire) prior to 1563. This was, and still is, a flax growing area. The first wave of lacemakers from the continent came in 1563 to 1568. They were Flemish Protestants who left the area around Mechelen (Mechlin / Malines) when Philip II introduced the Inquisition to the Low Countries:

Lace was probably made in the Eastern Counties (Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire) prior to 1563. This was, and still is, a flax growing area. The first wave of lacemakers from the continent came in 1563 to 1568. They were Flemish Protestants who left the area around Mechelen (Mechlin / Malines) when Philip II introduced the Inquisition to the Low Countries:

- 1563: Twenty-five recent widows, makers of bone lace, settled in Dover, Kent; 400 settled in Sandwich, Kent;

- 1567: It is estimated that 100,000 left Flanders when the Duke of Alva became head of the Spanish Catholic Army. Most of that number came to England.

The second wave of lacemakers, many from Lille, left in 1572 after The Massacre of the Feast of Saint Bartholomew. Exactly how many is not known but many hundreds came to Buckinghamshire and Northampton.

From this time Bucks point lace developed: it is a combination of Mechlin patterns on Lille ground.

In 1586 Lord William Russell, son of the Duke of Bedford, owned property near Cranfield, Bedfordshire. This is about 10 miles from Olney. He had fought for William the Silent in the Low Countries and he was married to Rachel, daughter of the Huguenot Marquis de Rivigny. He invited many refugees to settle under his protection.

Another English gentleman, who had fought for William of Orange, was George Gascoigne: he invited other Huguenots to settle near his manor at Cardington, Bedford.

Huguenot emigration continued until the Edict of Nantes in I598. However, when the Edict was rescinded in 1685 by Louis XIV, there was another wave of religious refugees. About 10,000 left Burgundy and Normandy. The lace makers found their way to the by now well-established lace villages in the counties of Buckingham, Bedford and Northampton. Flemish and Huguenot names still common in this area are listed below; naturally, most have been Anglicised over time.

| Olney | Minard (Mynard) Raban Cattell Rubythorn Mole (Mohl) |

| Buckingham | De Ath Rennels |

| Other places | Dudeny (Dieu donner) Nurseaw Milliner Hillyard |

| Non-specific | Perrin Waples Lathall Francy Simons Cayles Bitchiner Le Fevre Sawell Le Fevier Glass Conant Vaux |

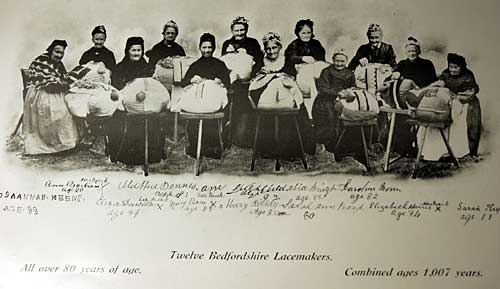

Families of agricultural workers and the more lowly artisans supplemented their income by working at the lace; men and boys as well as women and girls.

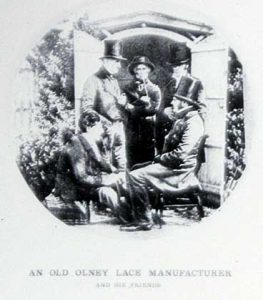

The 1798 Posse Comitatus for Olney, a military census, drawn up due to concerns of a French invasion arising from the Revolutionary Wars (1793-1802), included able-bodied men between the ages of 15 and 60 who were not Quakers, clergymen or already serving in a military unit. This list identifies male lace pattern makers, dealers, lace makers, collar makers and lace pillow makers and lace bobbin makers.

The 1803 Militia Lists for three local villages include:

| Hanslope | George Hancock | lacemaker |

| North Crawley | James Cobb | lacemaker |

| Emberton | Chas. Cooper | lacemaker |

Indeed in good times, the trade paid 1/- to 1/3 (one shilling to one shilling and threepence ) a day; much better than the wages of agricultural labourers. Nor was this craft limited to Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire, but was carried on in Northamptonshire as well. The Northampton Militia lists of 1777 states that there were between nine and ten thousand young women and boys employed in lacemaking in and around Wellingborough and about nine thousand involved in the trade around Kettering. Nevertheless, it was the counties of Buckinghamshire and Bedfordshire which were principally involved. For example the town of Newport Pagnell…

‘…flourishes greatly, by means of the lace manufacture… There is scarcely a door to be seen, during Summer, in most towns, but what is occupied by some industrious pale-faced lass; their sedentary trade forbidding the rose to bloom in their sickly cheeks.’

Thomas Pennant – “The Journey From Chester to London 1779”

Olney in the Eighteenth Century had a population of around two thousand, and about five hundred houses. William Cowper wrote:

Olney is a Populous place, inhabited chiefly by the half-starved and the ragged of the Earth.’

Cowper wrote in a letter to Joseph Hill, dated 8th July 1780:

‘I am an Eye Witness of their poverty and do know that Hundreds of this little Town are upon the Point of Starving and that the most unremitting Industry is but barely sufficient to keep them from it… there are nearly 1200 lacemakers in this Beggarly Town.’

Cowper was very critical of the Bill before Parliament for the removal of the tariff on Irish goods which would destroy the market for English lace.

John Newton was equally forthright in his description of the town and surrounds:

The people here are mostly poor – the country low and dirty.’

He came to Olney in 1764 full of plans to help “the poor ignorant lacemakers”. Thanks to Newton’s patron, John Thornton, a rich merchant, he had £200 per annum to keep open house and to distribute to the poor and needy. Unfortunately when Newton left in the winter of 1779/1780 this bounty ceased.

The Decline of Bobbin Lace

Two Acts of Parliament influenced the decline of the bobbin lace industry:

- the Education Act (1870 in England & Wales, 1872 in Scotland and elsewhere) providing free, compulsory, elementary education for all children up to the age of 13;

- the Workshops Act setting out minimum requirements for hours worked and conditions of employment.

These Acts, together with the competition from machine lace and from imported lace, put the industry into terminal decline by the late 19th century. Designers ceased to work and there was a danger that old skills would die out. Patterns had become corrupted with time and the quality of the lace produced was poor.

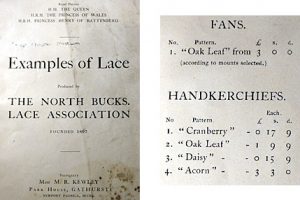

Philanthropic Movements such as the Society for Promoting Industrial Villages were formed to help co-ordinate the collection, sales and standard of the lace produced, and to enhance the happiness of its workers.

Such societies often romanticised the lace makers and the industry. They did, however, fulfil most of their aims; often through aristocratic and royal patronage. Countess Spencer was the President of the Midlands Lace Association. The Duchess of York (later Queen Mary), ordered 330 yards (301.62 metres) of Buckinghamshire Point. Queen Victoria in 1896 placed an order so large that an entire Winter’s work was guaranteed for many.

Locally, Harry Armstrong set up the Bucks Cottage Workers’ Agency in 1906.

Harry Armstrong was born in Stoke Goldington in 1886: his parents ran a grocery shop.

By the turn of the century, many local women had given up lacemaking because there was no regular market. Armstrong saw that lace making could continue if there was a means of collecting and marketing lace made by home-based workers.

To that end, he set up, in 1906, the Buckinghamshire Cottage Workers’ Agency in an outbuilding in the back garden of his family home.

One of his marketing ploys was to exploit lacemakers’ plight shamelessly by appealing to the public’s better nature in advertisements in various publications such as Needlecraft Monthly Magazine: another ploy was to trade as a woman!

For example:

‘Buy this lace direct off the Cottage Workers and encourage this industry. Mrs. Harmstrong [sic].’

‘It is the duty of every English lady to encourage a Home Industry. Mrs (Nellie) Armstrong.’

The following is a handwritten letter circa 1920:

‘Dear Madame,

Owing to the cold winds of adversity most of the Village Lace-makers are practically destitute and in dire need of immediate help.

Should you be able to buy but one piece of lace it would be a good deed and help to keep the fire burning in some poor Cottager’s home.

With apologies for troubling you in these trying times.

Yours truly,

(Mrs.) H. Armstrong’

By 1909 Armstrong moved his premises to Midland Road, Olney in order to be near to better rail and postage services. The premises consisted of offices, warehouse and a sewing room where lace-trimmed trousseaux were made.

In 1911 he won a gold medal at the Festival of Empire & Imperial Exhibition at Crystal Palace.

Between 1911 and 1914 Armstrong published a 144-page mail order catalogue, and adverts printed in 1916 state that the Agency gave regular employment to upwards of 600 cottage lace makers who worked in their own homes.

In 1919, he published Thomas Wright’s book “The Romance of the Lace Pillow”. This is still in print and on sale in the Museum shop as well as online:

The business flourished and in 1928 Armstrong had The Lace Factory built by George Knight in the High Street, Olney. The carving and lettering were by a Northamptonshire sculptor. A free-standing carving over the door was removed for safety reasons and eventually ended up in the courtyard of the museum.

This sculpture depicts a bobbin winder, flash stool, bobbin stand and firepot. The Museum has a photograph, below, taken in 1918 of a group of lace-makers with those items (except the bobbin stand), all of which are on display in Museum, and illustrated on this site.

The Agency continued throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Armstrong won numerous awards, including a gold medal at the Paris exhibition in 1925. He died unexpectedly in Scotland in 1943, following a short illness. He is buried in Stoke Goldington churchyard.

The Lace Factory was used by Polaroid during the remaining war years and was then taken over as a lampshade factory in the 1950s. 1988 saw its conversion to flats & apartments but it still remains a striking feature of the High Street

For more about Harry Armstrong and the Bucks Cottage Workers’ Agency see the Stoke Goldington Village website.

ELIZABETH KNIGHT’S TALK ON HARRY ARMSTRONG on the ODHS website

CIS ELDERTON INTERVIEW AT HARRY ARMSTRONG’S LACE FACTORY on the ODHS website

Working Conditions and Health

As women often worked at the pillows for ten to twelve hours a day, little time could be spared for domestic chores. A woman was employed in the Town of Olney to do ordinary mending. Servants were hard to get; women could earn more at lace-making and they had more independence.

William Cowper commented to John Newton, who was trying to find a nursemaid for his adopted daughter (his niece Betsy Catlett):

‘…the only thing a girl would dandle on her knee in these parts was a lace pillow.’

Poverty is relative: the lacemakers could earn higher wages than farmworkers but only by unremitting toil – and there were other disadvantages: if their children were not in lace schools, the boys especially, roamed the streets in gangs getting into all manner of mischief.

Also, their health suffered.

Also, their health suffered.

‘The women and girls (of Olney) have a bleached appearance.’

Mrs E. Wilson ‘Olney and the Lacemakers’, 1864:

Evidence of the poor health of lacemakers is to be found in The 6th Report of the Medical Officer of the Children’s Employment Commission:

Between the ages of 15 and 25:

‘More than double the number of females died of tuberculosis and other lung diseases than did males.’

This pattern of ill health was laid down in poorly ventilated overcrowded lace schools that girls were sent to from a young age. Silver End was reported as

Mrs Clara Webb told a story which indicates conditions in the lace-making industry. She remembers walking with her mother, shortly after World War One, from Paulerspury to the other side of Towcester (some 15 miles, 24km) to deliver and receive payment for some lace which had been privately ordered. On arriving Mrs Herbert and Clara were informed by servants that the mistress of the house had left word that “the lace was no longer wanted; fringes being all the rage now”.

The story illustrates several points:

- that the changes in fashion after the First World War hastened the demise of the bobbin lace industry;

- that only an order through the Lace Associations guaranteed payment;

- the treatment of the working classes by the more affluent!

The heyday of Lace Schools was the early to mid 19th century. Their purpose was to teach young children how to make lace and earn a little money for their parents. In addition, some reading and writing were taught. The quality of such teaching varied considerably from school to school.

At the two Lace Schools in Hanslope:

- the children started on the narrowest edging working 6 to 7 hours a day;

- they were paid 6d (6 pence) a day;

- they were not allowed to talk;

- “Children who were slow to learn had their noses rubbed on the pins and those who were inattentive had their hands rubbed raw for “looking off the pillow”;

- they were allowed ten minutes to scramble;

- another break was given over to breaking straw for stuffing pillows.

“Tells”

Jack be nimble

Jack be quick

Jack jump over

The candlestick.

This is an example of a tell. Tells were rhymes chanted by children in lace schools. Their purpose was to instruct, to alleviate the boredom of repetitive tasks, and to keep up a constant work rate. Here is another tell:

Needlepin, needlepin, stitch upon stitch,

Work the old lady out of the ditch,

If she is not out as soon as I,

A rap on the knuckles will come by and by,

A Horse to carry my lady about,

Must not look off till twenty are out.

Interpretation:

- ‘Needlepin’: a tool to make ‘stitch upon stitch’ – sewing;

- ‘Work the old lady out of the ditch’: pull your sewing loop through;

- ‘If she is not out as soon as I’: if you’re not as deft as I am;

- The ‘Horse’ is a stool for my ‘lady’: the pillow;

- ‘Must not look up’ etc: do not away from your work until you have set twenty pins.

Adapted from “Lace Villages” by Liz Bartlett, published by Batsford, London 1991[/wpspoiler]

Equipment

The design of the lace was transferred either to parchment or strong card from master cards and was called the “pricking”. Pinholes were pricked through and the pattern markings were added using Indian ink. The finished pricking was attached to the pillow using strong pins ready for the work to commence.

Traditionally, the pins were made of brass and varied in length and thickness. The choice of pin size was dependent on the thickness of the thread.

Traditionally, the pins were made of brass and varied in length and thickness. The choice of pin size was dependent on the thickness of the thread.

Thread was always a heavy charge on the lacemaker, costing her about a tenth of the price of her lace. Until the 19th-century fine linen was imported from the continent and there was a heavy-duty imposed on it. Before the middle of the 18th-century linen thread was always spun by hand.

A lace dealer told the House of Commons in 1699 that £5 to £15 worth of lace thread made lace to the value of £100.

In 1780 an importer calculated that the value of thread imported for the Buckinghamshire lace industry was £30,000 to £40,000.

By 1803 the duty had risen to 5/- (shillings) in the £ (pound).

Early in the 19th-century fine cotton thread was introduced. This was sometimes called gassed thread because it had been passed through a gas flame to remove loose fibres. Linen, however, made the most durable and best lace. Linen was sold in skeins, its fineness being indicated by numbers.

Cotton was sold in packets containing “parcels”, each of which consisted of a specified number of “slips” according to the fineness; thus 14 slip was extremely fine and 3 slip the coarsest in use.

Gimp thread, a thicker, more lustrous yam, was used to outline the pattern in point ground lace and was also graded by number.

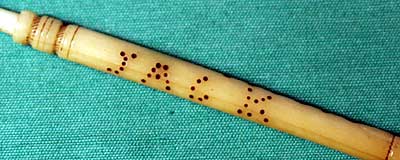

The Story of the “Jack Alive” Bobbin

At the end of the 19th century there lived in the nearby village of Lavendon an illiterate lacemaker, whose son, Jack, was a sailor.

Wherever he went in the world he had a bobbin made for his mother. On receiving these tokens she knew her son was still alive.

These bobbins can be useful in helping to establish the years in which a bobbin-maker was producing bobbins. There were six executions in the nineteenth century which were commemorated on inscribed bobbins.

- ‘Matthias and William Lilley 1829’

Bobbins with this inscription were made to commemorate the execution of two brothers hanged at Biddenham for the attempted murder of a game-keeper who had caught them poaching. There was some doubt about whether the gun they were carrying went off accidentally, or whether it was a serious attempt to kill the gamekeeper, but they were found guilty of attempted murder, which was a capital offence at the time. It is thought that – unlike the other five ‘hanging’ bobbins – these bobbins were made out of sympathy for the two unfortunate young men. - ‘Sarah Dazeley Hung 1843’

Sarah was hanged at Bedford at the age of 22, for the murder of her second husband whom she poisoned with arsenic. There is a strong possibility that she was also responsible for the premature death of her first husband. - ‘Joseph Castle Hung 1860’

Joseph Castle cut his wife’s throat and threw her body over a hedge. He met with his ‘just deserts’ on the scaffold of Bedford Gaol in 1860. It is said that his wife’s family gave a party on the evening of the execution, and each guest was given a bobbin with this inscription. Certainly, many such souvenirs were sold that day and it is one ‘hanging bobbin’ fairly commonly seen today. - ‘Franz Muller Hung 1864’

This is the only execution commemorated on a bobbin which did not take place in Bedford. It had created wide public interest as Muller was the first man to commit murder on a railway train, and was executed for his crime at Newgate Prison. - ‘William Worsley Hung 1868’

William Worsley and Levi Welch murdered a man at Luton, but Welch turned king’s evidence, accused Worsley of striking the critical blow, and thus escaped the gallows. Worsley was the last man to be publicly hanged at Bedford and inscribed bobbins were extremely popular souvenirs, making this one of the most common of the six ‘hanging bobbins’. - ‘William Bull Hung 1871’

William Bull murdered Sarah Marshall, a harmless old woman who was probably half-witted. He was very drunk at the time and killed the poor lady in a particularly brutal manner, so there was great public satisfaction when Bull was brought to justice, and even though the hanging was not public, many people bought inscribed bobbins to commemorate the event.

Examples of Lace Pillows

The lace was made on pillows which were firmly stuffed with straw. There were two traditional shapes – the square and the bolster,

The square pillow began life as a square of hessian folded and stitched into an envelope shape. This sat on a three-legged bowed “horse”.

The bolster pillow was made from a rectangle of hessian stitched into a tube with a drawstring at each end. When well stuffed it took on a cylindrical shape. This rested on a trestle ”

Adequate lighting was an important consideration in lace making. In warm weather, the cottagers could work outside, or at an open door or window; but at night and during the dark days of winter the work was done by the light of candles.

A tall flash-stool or candle-block concentrated the light from a single candle and focused it on the lace -pillow exactly where it was needed.

The top or hole-board was pierced in the centre to take a nozzle. This was a wooden candle socket adjustable for the height of the candle. Around the nozzle were three, four or five holes to take the cups, i.e. wooden sockets which held the glass refracting flasks.

The flask or flash, a glass globe with a long narrow neck, was filled with snow water or crushed ice – the purest water available. It was then corked and inserted into one of the cups. Here it acted as a condenser or lens concentrating and whitening the candlelight. Other flasks were prepared and mounted according to how many lace makers were working together.

By positioning the pillows around the flash-stool so that the candlelight fell in a concentrated beam on each, three to five lace-makers could work comfortably by the light of a single candle. This is the origin of the flashlight.

Most of the flasks were specially made for the purpose but round bottles, oil flasks and engravers’ flasks were all used.

Flash cushions, little open circles of plaited rush, were sometimes used as a rest for the flash. Hutches (baskets of plaited rush) packed with straw or rags, held and protected the flashes when not in use.

Flash-stools are mentioned in the Overseers’ Inventories at St Paul’s Church, Bedford dated 1772.

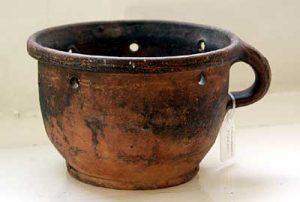

Thomas Wright records the use of “fire-pots” or “dick-pots” or “chad-pots” to keep the workers warm. These pots, which were pierced with holes could be made from earthenware, brass or iron and they were filled with hot wood ashes or glowing charcoal.

Thomas Wright records the use of “fire-pots” or “dick-pots” or “chad-pots” to keep the workers warm. These pots, which were pierced with holes could be made from earthenware, brass or iron and they were filled with hot wood ashes or glowing charcoal.

The women placed them near their feet, often tucking them beneath the voluminous skirts worn at this time. The women could not sit near fires, whether wood or coal, because the smoke would dirty the expensive lace thread.

In earlier times the lacemakers would work in the lofts above cattle byres in winter. The heat generated by the bodies and breath of the animals stabled below would arise and help keep the workers warm.

Despite rather primitive conditions, good workers would keep their hands scrupulously clean in order not to soil the lace and so lower its value.

Examples of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire Lace

Bedfordshire lace

Buckinghamshire lace