Slavery and Abolition

William Cowper & John Newton - Slavery and Abolition

To find out more and to download free education materials go to: ‘William Cowper and John Newton: Britain’s Role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade & Abolition‘

During the time William Cowper & John Newton lived in the town of Olney (Newton from 1764 – 1779 & Cowper from 1767 – 86), throughout the Country the slave trade was seen as a respectable profession and a way to make money. Slavery was accepted by the vast majority of people as custom and practice.

Some protests had been made in the late 17th century, principally by the Quakers. In England the Society of Friends raised a protest in 1727 and some prominent churchmen raised their voices, such as John Wesley in 1774. It was not until 1787 that the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the African Slave Trade was established. Nine of the twelve founding members were Quakers, including six who had presented a petition against the slave trade to Parliament in 1783. Also as members of the committee were Thomas Clarkson, Granville Sharp and Philip Sansom.

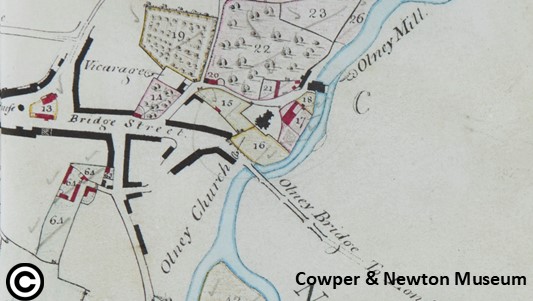

Late 18th Century Olney

In the 18th century, Olney was a rural town described by one person as ‘a populous place inhabited chiefly by the half-starved and ragged of the earth’ or as Newton put it ‘The people here are are mostly poor – the country low and dirty’. There was no resident great landowner, but a weekly market was held, shops, pubs and inns frequented and a cottage industry of near on 2,000 laceworkers helped to keep most local families from the need to call on Poor Relief.

The Legacies of British Slave Ownership database, which records all those individuals who were recompensed by the British state at the abolition of slavery in 1833, identifies one Olney resident in receipt of money. However, there is no doubt that even in rural Olney, many lives and livelihoods would have been associated with the material and economic benefits that were a result of the work of enslaved people across the other side of the World.

The Cowper & Newton Households

In 1768 Mary Unwin, her daughter Susanna and lodger William Cowper moved in to Orchard Side, now the Cowper & Newton Museum. Although not a large house compared to her previous home in Huntingdon, and small in comparison to the houses of Cowper’s relatives, letters and surviving objects tell of a comfortable life.

In 1764 the newly ordained Rev John Newton had moved into the Vicarage in Olney, which was soon enlarged for him by his patron the Earl of Dartmouth. He was on a curate’s pay, but John Thornton, a wealthy London businessman, made a large donations for Newton to use to help the ‘poor and needy’ in the parish.

‘We have daily new reason to thank your Lordship for our dwelling, as well as for the satisfaction you are pleased to express in our accomodation I shall say no more upon the head of expense, only that it is more than I deserve.’

Letter to the Earl of Dartmouth 18th November 1767

Newton’s life in Olney was in contrast to his previous life, working in the slave trade, both on land off the coast of Sierra Leone and at sea as a First Mate and then Captain of slaving ships. After leaving the sea in 1754, and a period of illness and unemployment, he became a Tide Surveyor at the Port of Liverpool. It was from Liverpool docks that so many slaving ships set sail for Africa.

Slavery & Abolition at the Cowper & Newton Museum

Just as the slave trade and abolition were part of 18th century life, when you visit the Museum to ‘Relive Georgian Life’ in the home of William Cowper, you will also find out more about the part that Cowper played in the campaign to abolish slavery and Newton played as an active participant in both the slave trade and the campaign against slavery.

William Cowper

William had condemned the slave trade in his poem ‘The Task’ written whilst he lived at Orchard Side. Later he was encouraged to write poems specifically for the campaign begun in 1787. One of these poems became an anti-slavery ballad, becoming popular in both monied households and with those who could not read or write as they could more easily learn the words when set to music. Part of this correspondence can be read in his published letters for the year 1788.

Extracts from the longer poems and those written specifically for the campaign are available from Professor Brychan Carey’s website William Cowper’s Slavery Poetry

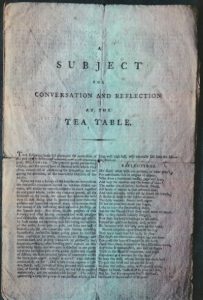

Also on display is the pamphlet ‘A Subject for Conversation at the Tea-table’ which included Cowper’s poems and was designed to encourage people to discuss the issues and as a call for action.

‘This little piece, Cowper presented in manuscript to some of his friends in London; and these, conceiving it to contain a powerful appeal in behalf of the injured Africans, joined in printing it. Having ordered it on the finest hot-pressed paper, and folded it up in a small and neat form, they gave it the printed title of “A Subject for Conversation at the Tea-table.” After this, they sent many thousand copies of it in franks into the country. From one it spread to another, till it travelled almost over the whole island. Falling at length into the hands of the musician, it was set to music; and it then found its way into the streets, both of the metropolis and of the country, where it was sung as a ballad; and where it gave a plain account of the subject, with an appropriate feeling, to those who heard it.

Thomas Clarkson, The History of the Abolition of the African Slave-Trade, vol. 2 [1808]

Other objects which were created for the Abolition Campaign are also on display in the Georgian Life Room and The John Newton – Early Life & Slave Trade Room.

John Newton

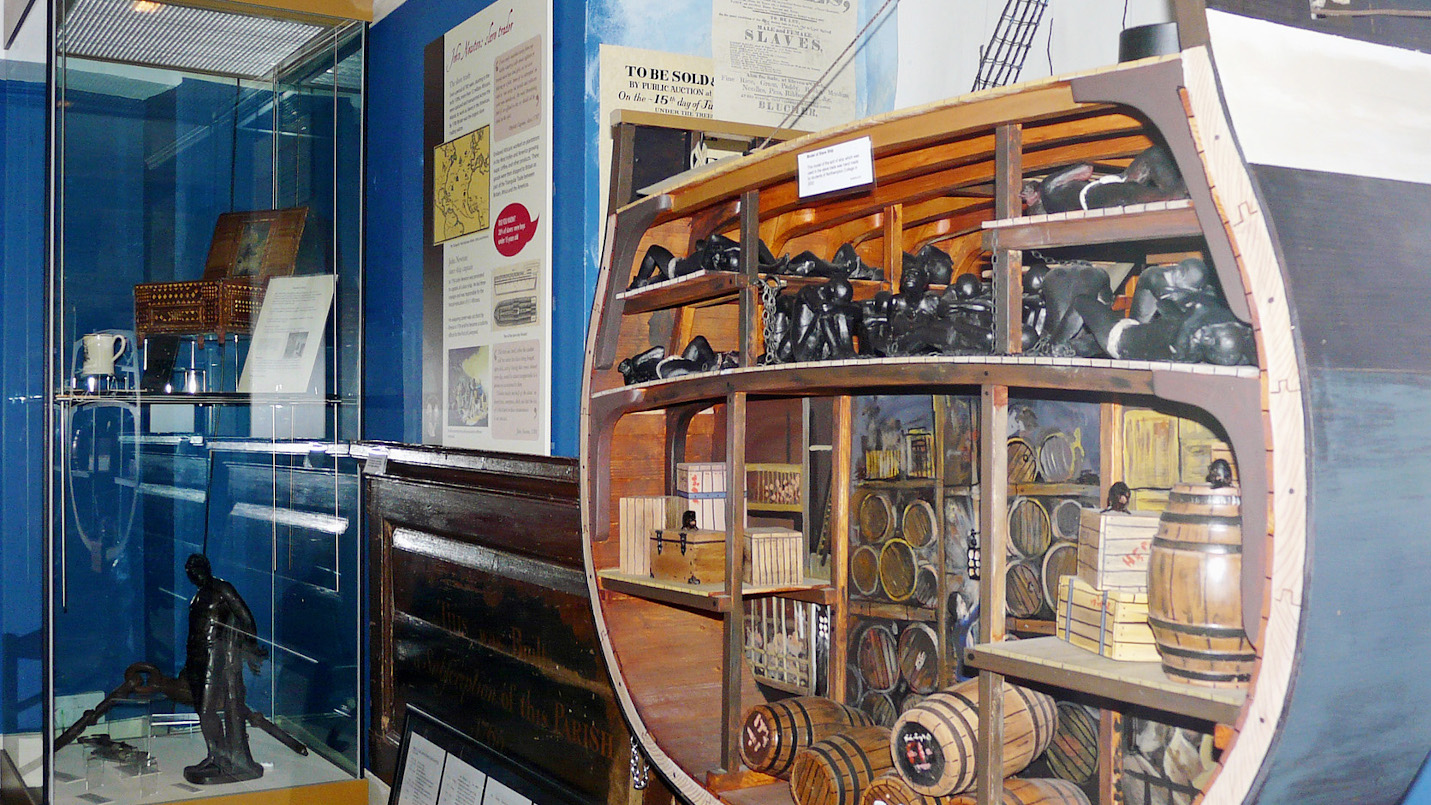

The John Newton – Early Life & The Slave Trade Room contains objects related to the slave trade and tells of Newton’s own participation.

‘It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was, once, an active instrument, in a business at which my heart now shudders.’

In 1772, at home in the Vicarage in Olney, Newton tells us in his diary that:

‘James Albert, a Black born in the inland country somewhere behind the Gold Coast, came to see me. At first I was shy – but I found reason afterwards to receive him with gladness as a singular instance of the Sovereignty and Providence of God. He was brought off the coast when a boy – carried first to Barbadoes then to New York, where he was sold to a German minister who was the instrument of his conversion. He is now upwards of 60, the last 12 years, he has lived in England. Spoke at the Great house from 1 Peter 5:7. Hope it was a good day.’

Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, also known as James Albert, was an enslaved man and is considered the first published African in Britain. – A Narrative Of The Most Remarkable Particulars In The Life Of James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw, An African Prince, As Related By Himself, James Albert Ukawsaw Gronniosaw

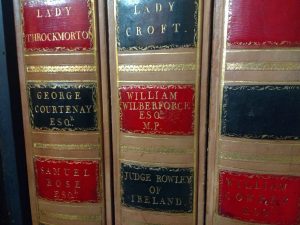

With the establishment in 1787 of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the African Slave Trade, Newton then threw his weight behind the campaign. For the rest of his life he sought to give his support:

Mentor to William Wilberforce who become the voice of the abolitionist movement in parliament.

Mentor to William Wilberforce who become the voice of the abolitionist movement in parliament.

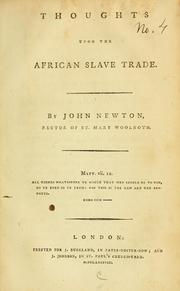

Building on his autobiography, he published the influential pamphlet ‘Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade’ which was sent by The Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade to each member of both Houses of parliament.

Gave evidence to the Privy Council assembled to hear witnesses on the slave trade and the Select Committee of the House of Commons.

Provided evidence for the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (later named the Anti-Slavery Society)

Spoke from his church pulpit in London against the trade and in support of Abolition.

‘Though unwilling to give offence to a single person, in such a cause, I ought not to be afraid of offending many, by declaring the truth. If, indeed, there can be many, whom even interest can prevail upon to contradict the common sense of mankind, by pleading for a commerce so iniquitous, so cruel, so oppressive, so destructive, as the African Slave Trade!’

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

You will find more resources on our Learning page and John Newton page.

We are also continuing to work with Royal Holloway, University of London to support the development of further educational resources.

Find a listing for National events on the Black History website here

References & Resources:

Letters from John Newton to the Earl of Dartmouth: Historical Manuscripts Commission XV Report, Appendix, Part 1, The Manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth, iii (1896 )

‘Journal of a Slave Trader (John Newton 1750 – 1754)’ Edited by Bernard Martin and Mark Spurell, Epworth Press 1962. The original journals are owned by the National Maritime Museum. Some pages have been digitised,

‘Letters to a Wife’ published letters from John Newton to his wife Mary (Polly) Newton nee Catlett whist he was aboard ship. Some original letters are digitised on the Lambeth Palace website

John described his life in the land based and sea based slave trade in his ‘Authentic Narrative’

He described is own participation in the slave trade as well as his wider experiences of the slave trade in a pamphlet for the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade: Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade

Related articles from The Cowper and Newton Journal:

‘Cowper, Slave Narratives, and the Antebellum American Reading Public’ Author: Katherine Turner

‘Two Curates, Two Baptists and a Poet – Olney and the Abolition of the Atlantic Slave Trade’ Author: Thomas Martin,

‘Slave Ships’ Author: James Walvin