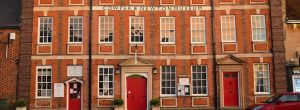

Here we look at two rings in the museum collection which date from the mid-eighteenth century and are said to have belonged to William Cowper. We also discuss the romantic nuances associated with them.

Both rings came to the museum from descendants of the Cowpers and Johnsons, and both were linked by family tradition to the story of Hercules and Omphale, Queen of Lydia. One is a seal ring, and was purchased as part of the Cowper Johnson Archive in 2007. The other, a cameo ring, was given to the museum by Mary C. Barham Johnson in 1992.

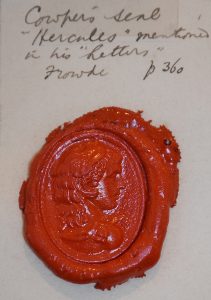

On the seal ring Omphale is shown wearing a lion’s skin on her head. The seal itself is carnelian, a semi-precious gemstone, and is carved in intaglio, that is, with the image indented rather than in relief There is a wax impression from it on display in the museum.

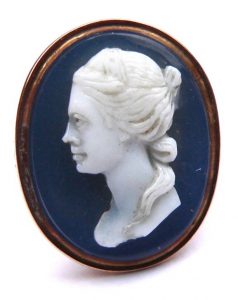

The other ring contains a cameo carved from agate, a hardstone. The head and features are crisply cut. The sculptor has cleverly exploited the natural striping in the stone to carve away some of the upper white layer, thus allowing the head to stand out in relief, and in clear contrast to the lower, background layer of dark blue. The cameo has a plain gold setting and a narrow gold ring band.

The legend of Omphale and Hercules

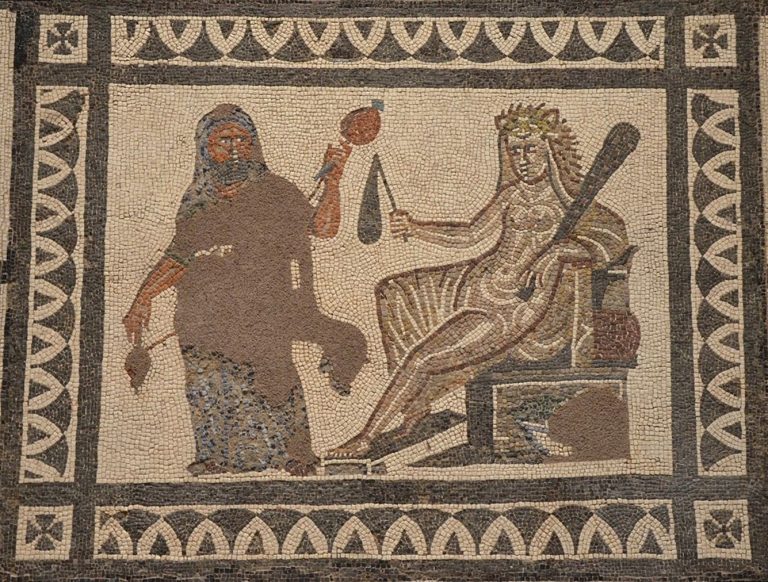

The best-known legend about Omphale tells of her relationship with Heracles, a Greek hero and demigod, the illegitimate son of Zeus and Alcmene. However, Heracles is better known by the Roman version of his name, ‘Hercules’, so we will stick with that in the remainder of this article (Cowper also uses the Roman form). Before his dalliance with Omphale, Hercules underwent various trials and adventures. Amongst these was a brief bout of insanity engineered by Zeus’ wife, the goddess Hera, in revenge for her husband’s infidelity. In a state of frenzy Hercules killed his wife and children, and when recovered had to do penance for the crime – the famous twelve ‘Labours of Hercules’.

These tasks were extraordinarily demanding. Many of them involved encounters with dangerous animals and, to succeed, Hercules needed to exercise superhuman powers. In the first Labour, he had to slay the Nemean Lion, a ferocious animal with magical properties, which could not be killed by a mere mortal. These, and other stories of his derring-do and physical magnificence, created the image of Hercules as an icon of Western masculinity. His name is associated with courage, strength and ingenuity, and he is also known for his sexual prowess with both men and women.

All of this adds a special frisson to his experience with Omphale. It resulted from another slaying – he had accidentally killed a friend – and to expiate this crime he was sold as a slave to Omphale, a foreign queen. How was the mighty Hercules fallen! For a time he had to endure the humiliation of serving a mere mortal, a woman, and an oriental barbarian to boot. To make matters worse, she made him dress as a woman and do woman’s work.

Many artists and writers have had fun with this part of the tale. He is often depicted, for example, as carrying a basket of wool to help Omphale and her female assistants with their spinning. In the poet Ovid’s version, while Hercules wore a dress, Omphale draped the Nemean Lion’s skin over her shoulders (on our ring she wears it on her head). So the usual roles and appearance of the two are reversed: our alpha-male hero is reduced to the effeminate underling of an all-powerful woman.

So how did Cowper come by the seal ring?

The following letter of 31 January 1789, from Cowper to his cousin Lady Harriot Hesketh, implies that the ring was given to him by her, but as we shall see in a moment that may not be the whole story. Cowper is recounting a visit to his friend and former schoolfellow, now the owner of nearby Chicheley Hall, Charles Chester. He,

… if not a professed virtuoso, is yet a person of some skill in articles of virtù, produced for our amusement a small drawer furnished with seals and impressions of seals ― antiques. When he had displayed and we had admired all his treasures of this kind, I took the ring from my finger, which you [i.e. Harriot] gave me, and offered it to his inspection, telling him by whom it was purchased, where, and at what price. He examined it with much attention, and begged me to let him take an impression from it. He did so, and expressed still more admiration. I put it again on my finger, and in a quarter of an hour he begged to take another. Having taken another, he returned it to me, saying, that he had shown me an impression of a seal accounted the best in England (if I mistake not, it was a Hercules, an antique in possession of the Duke of Northumberland), but that he thought mine a better, and much undersold at thirty guineas. He took the impression with much address, and I never myself viewed it before to so great advantage.

In 1890 a large exhibition (the ‘Hanover’ exhibition) opened at the New Art Gallery, Regent Street, London, of historic objects from the Georgian period. These were mostly paintings but included some ‘relics’ and mementos of prestigious people. The Cowper Johnson family loaned Cowper’s portrait as painted by Abbott, the Omphale seal ring, and the ball of yarn Cowper had famously wound for Mrs Unwin while living at Olney.

It is interesting that the family offered the ball of wool along with the Omphale seal ring, given their combined significance for the tale of Hercules performing womanly tasks. But it suggests that they, along with Cowper but unlike the Greeks, saw no dishonour in such activity.

In the exhibition catalogue, the entry for the ring states that it had been given to Cowper by ‘his cousin, Theadora Cowper’. Theadora was Harriot’s sister and Cowper’s one-time fiancée. The catalogue entry may have been a mistake, or it may be that Theadora gave Cowper the ring via Harriot, who apparently transmitted messages between the two in her correspondence. If the latter, it would explain a great deal, as it is easy to understand that Cowper would treasure a present from his former fiancée and be happy to wear the seal. The connection to Omphale and Hercules makes sense too: again, it is easy to imagine a teasing private joke between them, casting Cowper as a slave to his love for Theadora. We shall return to the three-way relationship between Cowper and the two sisters later

But if it was Lady Hesketh herself who gave Cowper the Omphale seal ring, she may have had in mind Cowper’s role as translator of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, the most ambitious project of his career as a poet. Lady Hesketh persuaded her friends to subscribe to its publication, and it was eventually issued in two magnificent volumes in 1791. What better way to commemorate her cousin’s labours than by giving him a valuable ring, symbolic of the Labours of Hercules? Thirty guineas, cheap at the price as Cowper implies in his letter, was a considerable sum at the time. The seal ring was a gem such as wealthy collectors and aristocrats might desire, and we know that Lady Hesketh moved in such circles.

Either theory may explain why Cowper was happy to wear the ring in spite of its potentially demeaning associations. Even so, the implied references to insanity, to weakness, to a domesticated, somewhat foppish, bachelor surrounded by females, sound rather too near the bone if we look quizzically at Cowper’s life – particularly in Olney and Weston Underwood, where his companion was the widowed Mrs Unwin. We need to examine some of his relationships with women.

Cowper and his female friends

Cowper, it seems, was attractive to women. On a good day he was excellent company, amusing, enjoying jokes and knowing how to charm by paying detailed, personal attention to the people he was with. Sometimes, indeed, his behaviour could be interpreted as being a little flirtatious. His many letters testify to this, describing in detail both to men and women his thoughts, feelings, and daily doings. As he says:

I am fond of writing as an amusement but I do not always find it one… Being rather scantily furnished with subjects that are good for anything I often find myself reduced to the necessity, the disagreeable necessity, of writing about myself.

He also claims that he likes to write:

…entirely clear of the charge of pre-meditation…with simplicity.

His tendency to talk about himself in an easy, natural way (allowing for some of the conversational conventions of the mid-eighteenth century) means Cowper’s letters can read like shared intimacies. It is reasonable to imagine that they flattered his recipients, particularly after he had become became a well-published, celebrated poet and translator of Homer.

The tone of his letters to ladies is perhaps lighter than that he used when writing to men, but otherwise there is little discernible difference. The overriding impression is one of concentrated and personal attention. What might be different is the effect it had on his readers – the apparent intimacy, while somewhat seductive to women, appearing as more comradely to men? So far we have only considered Cowper’s circle of friends in general terms. What of his closer relationships and the light these might shed on the puzzling, rather humiliating Hercules/Omphale associations implied by the seal ring?

Cowper’s mother

Cowper’s mother died when he was just six years old. Most biographers suggest this left a scar which never quite healed: she died just too soon, too early, in his life, leaving him vulnerable to the feelings of insecurity and worthlessness he would later describe. A lasting sense of loss is evident in some poignant lines Cowper wrote when he was 59. One of his female cousins had sent him a portrait of his mother, and this gift prompted a vivid childhood memory: the floral dress she wore as she stroked his hair.

Could time, his flight reversed, restore the hours,

When, playing with thy vesture’s tissued flowers,

The violet, the pink, and jessamine,

I pricked them into paper with a pin,

(And thou wast happier than myself, the while,

Wouldst softly speak, and stroke my head, and smile)

Could those few pleasant days again appear,

Might one wish bring them, would I wish them here?

‘On the Receipt of my Mother’s Picture out of Norfolk’, lines 74-81

Sad indeed. According to some psychological critics, this early trauma may have contributed to Cowper’s indecisiveness and his unwillingness to commit to marriage. Some suggest too, that it contributed to a certain weakness and effeminacy of character which they go on to connect with probable impotence.

This sort of theorising has been used to try to illuminate Cowper’s long relationship with Mrs Unwin. Perhaps because of its enduring and apparently unsexual nature, some people have been quick to raise their eyebrows and to query Cowper’s masculinity. From this perspective Cowper’s ownership of the Omphale seal ring does look a little puzzling.

Mrs Unwin

Cowper got to know Mr and Mrs Unwin through lodging with them for two years in Huntingdon. They became good friends, with Cowper particularly admiring their devout Christian regime. On the death of her husband, and with the help and encouragement of the Reverend John Newton, Mrs Unwin and Cowper moved to Olney and lived there together for 18 years. They then moved to Weston Underwood to share a home there. Clearly there was some concern about the propriety of the arrangement and perhaps for this reason the two became briefly engaged. But Mary Unwin was a very pious woman; the idea that there might have been any sexual intimacy between the two of them seems highly improbable. Their relationship was close, comfortable and usually described as like that between a mother and her son. There seems little reason to doubt this.

Cowper wrote of typical days and evenings spent with her in Olney, consisting of prayers, church, meals, the occasional game or shared domestic pastime, walks, and readings from the scriptures. At Weston Mrs Unwin used an attic room as her private space for prayers. Cowper commented on the peacefulness of such a domesticated life and of its rural setting. Significantly, in one letter to Mrs Unwin’s son William, he writes,

In the morning I walk with one or other of the ladies, and in the afternoon wind thread – thus did Hercules, and thus probably did Samson, and thus do I; and were both of those heroes living, I should not fear to challenge them to a trial of skill in that business, or doubt to beat them both. As to killing lions and other amusements of the kind, with which they were so delighted – I should be their humble servant, and beg to be excused.

So there we have it: Cowper knows the legend and, it seems, is proud to be associated with it. He gives no sense of feeling demeaned by performing ‘women’s’ work’. He was after all a very practical man and enjoyed all sorts of productive ‘hands on’ tasks in Olney, from gardening, building a glasshouse and mending a wall, to making nets to catch birds and knocking up wooden hutches for his tame hares. Cowper may have seen such ‘rural pursuits’, including wool-winding, as all of a piece and ungendered; more likely he simply was not bothered by any such distinction. He was happy doing whatever needed to be done. On this sort of evidence it is less surprising that Cowper should have owned the Omphale/Heracles ring. Indeed it is perhaps only from the perspective of later Victorian and twentieth-century commentators that his relationship with Mrs Unwin has looked strangely dependent and weak and, by extension, made to imply possible impotence or homosexuality.

Let us look at some of his other key female friendships to see if these shed further light on Cowper’s character and values and their relevance to his ownership of the Omphale ring.

Theadora and Harriot – Cowper’s cousins

In his late teens and early twenties Cowper appears to have led a normal enough life as a young man about town. He wrote, for example, to an old school friend, nicknamed ‘Toby’, to comment on the idea of marriage – its pros and cons – and to tease Toby about his rakish London ways. But he evidently enjoyed a bit of city high life himself. He was, he said:

…Dancing all last night; in bed one half of the day and shooting all the other half…

Also, we are told, he was not above remarking on a well-shaped lady. There is not much sign of the more reclusive and shy Cowper of later years, nor indeed of the effeminate and impotent man of some later interpretations.

Cowper also wrote to Toby about Theadora, an important figure in any account of Cowper’s women. In the early 1750s, when Cowper was in his twenties, he enjoyed many hours with Theadora and Harriot at their home in Southampton Row. With these girls he ‘giggles and makes giggle’, and at this time there seems to have been much laughter, teasing and general good humour.

It is often said – by family and other commentators – that both Theadora and Harriot were in love with Cowper. But Thea is the one he fell for and to whom he became engaged. Their love affair ran a fairly typical course, if this snippet written to Toby is anything to go by. It relates to a minor row between them where she had called him a coxcomb – a bit of a conceited dandy:

All is comfortable and happy between us at present and I doubt not will continue so forever. Indeed we had neither of us any great reason to be dissatisfied and perhaps quarrel’d merely for the sake of the reconciliation – which you may be sure made ample amends.

Cowper wrote several poems dedicated ‘To Delia’― his poetical name for Theadora – which reveal his complete devotion to her. But in the end they did not marry. They were first cousins and both of them suffered from inherited mental problems, which led to periods of frightening melancholy throughout their lives. Thea’s father was concerned about the proposed marriage, partly because of their consanguinity and partly due to a recent breakdown in Cowper’s health. The engagement was eventually broken off. Much pain, much sorrow, was suffered all round at this point. Theadora is said never to have recovered and to have been rarely, if ever, directly mentioned to Cowper again by friends and family.

If Theadora was the passion of Cowper’s life, her sister Harriot was his stalwart friend; someone he loved deeply but with whom he was not ‘in love’. In August 1763 he writes to her:

So much as I love you, I wonder how the deuce it has happened I was never in love with you.

But they corresponded often and Harriot (by now married and sometimes at court) used to exchange London gossip for Cowper’s country news. Harriot also looked after him in later life, seeing to his general welfare and finances, and caring for him when his health failed. She also played an important role as a comforting reminder of happier, youthful days.

These were two significant women in Cowper’s life and in each case there is the sense of ‘not quite, but almost’. Instead of wholehearted commitment we see an unrealised union with Theadora and a loving sistership with Harriot; and thus, more fuel for the debates about Cowper’s sexuality and his puzzling ownership of the Omphale ring.

Lady Austen

And so to Anna Austen – the lady Cowper spied in the street from his Olney window, liked the look of and had Mrs Unwin invite to tea so he could meet her properly. Apart from this rather dashing beginning, the exciting part about the relationship is that it seems to have got a little out of hand. Cowper, ever charming and enjoying being charmed in his turn by lively wit, laughter and a bit of novelty, perhaps unwittingly overdid his attentions.

For Lady Austen was not just an entertaining companion, she was also useful: she it was who suggested – or perhaps challenged Cowper to tackle – the subject (a sofa!) for his major work – The Task. She also told him the story of John Gilpin, a story that Cowper turned into an immensely popular comic ballad. Cowper clearly found her to be feisty and stimulating company. Perhaps fired up by this, he made the mistake of writing her an over-gallant poem in which he described how he felt when addressing her:

…that itching, and that tingling,

With all my purpose intermingling,

To your intrinsic merit true,

When called t’address myself to you.

On receiving this, Lady Austen must have felt it was in order to reciprocate by indicating that she was falling in love with Cowper. Then Cowper in his turn had to write and explain he was just being friendly – not amorous.

Lady Austen flounced off, but was soon back. Unfortunately, Cowper hadn’t learned his lesson. His habitual gallantry may have led him astray again, when he saw that Lady Austen had set a lock of his hair (he’d been persuaded to give her one) in an expensive, sparkling necklace. He ignored the dangerous implications of her publicly wearing this daring piece of jewellery, and instead managed to sound encouraging by writing her some further complimentary verse:

The star that beams on Anna’s breast

Conceals her William’s hair…

The heart that beats beneath that star

Is William’s well I know…

The ornament indeed is hers,

But all the honour mine.

Not a good move, and Lady Austen has to be turned away again. So here we have another ‘nearly’: perhaps Cowper was tempted by Lady Austen but then changed his mind. If so, what was this indecisiveness? Was it fear? If the latter, fear of what?

The single Cowper

There are other explanations for Cowper’s remaining single – apart from those arising from theories about his effeminacy. One which has considerable appeal comes from Cowper himself. In a letter to John Newton written in 1783, he says about his life in Olney:

It is the place of all the world I love the most, not for any happiness if affords me, but because here I can be miserable with most convenience to myself and with the least disturbance to others.

Such a view explains quite well his resistance to marriage or to any other close partnership. He sees himself as a problem, as someone who should not impose himself on another, his mother/son relationship with Mrs Unwin being the only allowable exception.

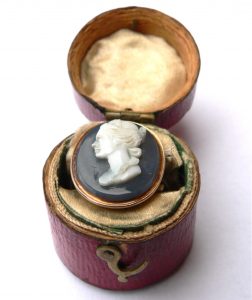

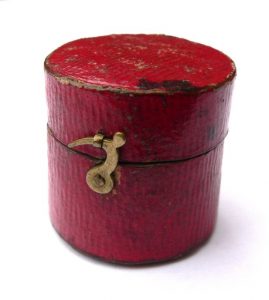

The cameo ring

This ring was donated to the museum by Mary C. Barham Johnson, of the family of Cowper’s cousin ‘Johnny’ Johnson, who preserved so many relics of the poet. After her death in 1997, her executor sent the museum what was believed to be the original ring case. Within it was a scrap of paper saying the ring had belonged to Cowper.

It contains a cameo, carved with a female head in profile. Miss Johnson, probably following a long-standing family tradition, believed this to be a representation of Omphale. Possibly the carving was based on a classical model already carrying Omphale’s name. We don’t really know.

But these details give us no clue as to how Cowper came to own the ring. And why a second such ring? There is no conclusive evidence on these questions, but there are a few possibilities.

The cameo is one size smaller than the seal ring that we know Cowper owned and was supposedly given to him by Theadora. This allows the speculation that the cameo was either a woman’s ring, or that Cowper wore it on his little finger. It is just possible that Cowper gave it to Theadora in exchange, as it were, for the seal ring. The problem with this theory is that Cowper never seemed to have any money, indeed he was always borrowing from and supported by his family. So we might wonder how he could afford it. Another possibility is that Theadora gave him this second ring as well as the seal, but perhaps at a much later date. We know that she sent him money and presents in the 1780s, but signed herself ‘Anonymous’. Amongst these were, for example, a desk and a snuffbox with a painting (by the celebrated Romney) of Cowper’s three hares on the lid.

There were probably many more gifts, but not usually much spoken of and with the giver always disguised as ‘Anonymous’. Whether Cowper knew these were from Theadora or not is uncertain, though it is usually denied. However, there is interesting evidence in a letter to Harriot, which tempts further speculation. He was writing to convey his pleasure in, and thanks for, the snuff box Anonymous had sent. So why say all this to Harriot? Cowper explains:

…it is also very painful to have nobody to thank for it. I find myself driven therefore, driven by stress of necessity…that I will constitute you my Thank- receiver General for whatsoever gift I shall receive hereafter, as well as for those I have already received from a nameless benefactor. I therefore thank you my cousin, for a most elegant present….

It is tempting to think that Cowper knew exactly who was sending him these gifts and wanted Theadora to know of his pleasure at receiving them. It is tempting too to imagine a continued bond between them and to see the giving and receiving of presents as a kind of secret messaging.

On this reasoning we might imagine Theadora wanting Cowper to know through the gift of the cameo that she still loved him – or to remind him of their youthful bond. Harriot was of course in touch with her sister and could convey disguised messages to her – such as the quoted extract above – from Cowper. Such speculation may give a rather romantic spin to the Tale of the Two rings but – is there a better, or more probable story, one that fits the evidence we have?

Cameos in history

As a postscript it is worth noting that cameos in general became very popular in the last three decades of the eighteenth century. The catalyst was the discovery of archaeological remains at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Many English and French artists, scholars, and engravers travelled to Rome and Naples to study the finds. They, and their work, became the inspiration for a revival of interest in classical art.

The new style ushered in by these finds was marked by refinement, fluid lines, and even a touch of romantic sentiment. There was also a preference for direct copying of early Greek and Roman models. (In the classical revival of the Renaissance, Greek forms tended to be re-interpreted rather than directly copied, and their mood was more severe.) This later, Neo-Classical, revival included a taste for cameos that more directly depicted Greek mythological scenes and figures.

And so back to our cameo: in style and subject it fits the fashion of the last decades of the eighteenth century. This suggests that it was probably purchased later in Cowper’s life – some time after, rather than during his courtship of Theadora.

Further reading:

Brunström, Conrad, ‘How did Cowper love women?’, The Cowper and Newton Bulletin, vol.3, no.2, Summer 2004.

Curry, Neil, ‘William and Theadora: an early love affair’, The Cowper and Newton Journal, vol.2, 2012.

Newey, Vincent, ‘Cowper’s return home: remembering and working-through in “On the receipt of my mother’s picture”’, The Cowper and Newton Journal, vol.8, 2018.

Seward, Tony, The Winner of Sorrow: A Novel, by Brian Lynch, vol.9, 2019.

Smith, K.E., ‘”Many a trembling chord”: Lady Austen as muse’, The Cowper and Newton Bulletin, vol.2, no.2, Summer 2003.

‘Honouring the Hares’ Find out more about the gifts received by Cowper from Theadora in this Blog article on our website.

Croft, James (ed.), Poems. The early productions of William Cowper; …With anecdotes of the poet. Collected from the letters of Lady Hesketh, 1825. This book includes the poems written by Cowper to his ‘Delia’, Theadora Cowper.