Since the start of the COVID pandemic, the National Archives at Kew has allowed free downloads of digital records from its website, a concession which will continue for as long as it’s only able to open for a very limited number of researchers. Seizing the opportunity, Trustee Amanda Molcher came up with an exciting discovery. It has always been assumed by Cowper’s biographers that he died intestate, as stated by his first biographer, William Hayley. But he DID make a will! – and here it is, expertly transcribed by Trustee Geoff Swindells (and slightly edited for clarity)

The will of William Cowper Esq dated 20 May 1777 (Ref PROB 11/347/107)

I Wm Cowper of Olney in the County of Bucks do make this my last Will and Testament. I give to Mrs Mary Unwin the sum of three hundred pounds or whatever sum shall be standing in my Name in the Books of the Bank of England at the time of my decease. I give to Mr Joseph Hill of Great Queen Street whatever Money of mine he may have in his Hands arising from the Bond of my Chambers in the Temple or may be due for the same at the time of my decease; and my desire is that such Money as he may have received on my account in the way of contribution and not remitted to me may be returned to those who gave it with the best acknowledgments I have it in my power to render them for their kindness. I have written this [in?] my own hand and the contents may suffice surely [to?] prove that I am in my Senses May 20 1777 Wm Cowper

So why did he decide to write his will in May 1777? His third severe period of depression had occurred in 1773-4, when he was so ill that the Newtons took him into the Rectory so that they could look after him. In October 1773 he had tried once again to commit suicide. He slowly recovered by the Spring of 1774, but was now so convinced of his own damnation that he never attended church again. Despite this profound spiritual crisis, the next few years saw him laying the groundwork for his emergence in the early 1780s as a bestselling poet. The fact that he decided in the Spring of 1777 to make a will could be taken as a sign of growing confidence in the management of his life, rather than of any concerns about his own impending mortality.

Although the depression of 1773-4 had caused him to break off his engagement to Mrs Unwin, he knew how much he owed to her devoted care, and clearly wished to make proper provision for her. Joseph Hill, a solicitor and attorney, was a lifelong friend and looked after all his business matters from 1764 (the museum possesses an album of over 170 original letters from Cowper to Hill and his wife).

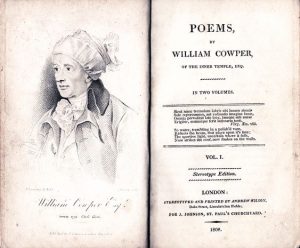

The reference to ‘the Bond of my Chambers in the Temple’ is interesting.** Although Cowper had given up any thought of pursuing a career in the law following his breakdown in 1763, he retained his chambers, and was proud of the connection. His first collection of poems was published as ‘by William Cowper, of the Inner Temple, Esq.’ The annual rent of 4 guineas was paid quarterly until his death in 1800, when the chambers reverted to the Inner Temple. Presumably any money Hill might have had in hand ‘arising from’ the Bond would have been rent paid by whoever was occupying the rooms at the time as sub-tenants.

Money ‘received on my account by way of contribution’ would no doubt have referred to gifts donated for his support by well-off friends and members of Cowper’s family. As we know, he was almost entirely dependent for his few comforts on handouts in cash and kind, having very little income of his own (the will dates from before he began to earn from his publications). Some of the most generous donations were made anonymously by his cousin and former sweetheart Theadora

Finally, the phrase ‘prove that I am in my senses’ might be thought to arise from his history of mental illness, but Geoff Swindells assures me that this was a stock formula in 18th century wills. More to the point, in view of its later history, is the assertion that the will was ‘written [in] this my own hand’.

As far as we know, this surprisingly brief document was indeed Cowper’s ‘last will and testament’, unrevised in the remaining 23 years of his life. After his death on 25 April 1800 Lady Hesketh and Johnny Johnson did not seem to be aware of its existence, and proceeded as if he had indeed died intestate. However, by 6 September that year, as evidenced by three subsequent addenda to the document, the will had been found, the handwriting vouched for by ‘Theodosia and Frances Hill, spinsters’, and administration granted formally to ‘Dame Harriot Hesketh’.

Additions to Cowper’s Will after his Death in 1800

Three significant additions were made to the will after Cowper’s death, on 18 August and 6 September 1800, and 26 November 1807. The complete text (unedited) of these may be consulted here but the gist of them is as follows.

On 18 August 1800 Joseph Hill’s daughters, Theodosia and Frances, made oath that they were ‘well acquainted’ with Cowper and ‘having frequently seen him write and subscribe his Name are thereby become well acquainted with his manner and character of Handwriting and subscription’. Accordingly, they believed that the will document was ‘all of the proper Handwriting and Subscription of him the said William Cowper Esquire deceased’.

On 6 September, the administration of all Cowper’s ‘Goods, Chattels and Credits’ was granted to ‘Dame Harriot Hesketh Widow the Cousin German and one of the next of kin of the said deceased she having been first sworn by Commission Duly to administer, no [?] Executor or Residuary Legatee being named in the said Will’.

Finally, on 26 November 1807, following the death of Lady Hesketh, administration of the will passed to Anne Bodham, widow, another cousin. Anne (1784-1846), a daughter of Cowper’s uncle, the Rev. Roger Donne, had married the rector of Mattishall in Norfolk and ensured her place in literary history by sending Cowper the portrait of his mother. This was the gift that inspired his poem ‘On the Receipt of My Mother’s Picture out of Norfolk’, with its beautiful evocation of his early childhood in Berkhamsted.

Administering the Will

I am much indebted to Trustee Kate Bostock for providing the following additional context for the will, teasing out the part played by each of the various individuals involved in the administration of Cowper’s estate. As so often, the dominant personality of Lady Hesketh looms large.

When Cowper died, neither Hill nor Rose nor Johnny Johnson nor Lady Hesketh was aware of a will. There is nothing about one in the indexes to King and Ryskamp’s five-volume edition of Cowper’s letters. It was Johnny who initially made all the necessary arrangements after Cowper’s death to settle his cousin’s affairs and sort out Cowper’s personal items.

Cowper’s cousin Johnny Johnson did much of Hayley’s research for the biography, and had lived with Cowper for several years. It may be that Cowper had forgotten to mention the will to him.

It is quite likely that Cowper gave a copy to Joseph Hill, his man of business. Samuel Rose (1767-1804) later took over the day-to-day running of Cowper’s affairs and Cowper wrote to both of them on matters relating to money and copyrights. Hill moved chambers from Chancery Lane to Savile Row in the late 1780s, so perhaps the will was forgotten then.

As the following extracts show, Lady Hesketh then took charge and set to work to administer Cowper’s estate in the apparent absence of a will. She became executor and was in touch with both Rose and Hill. Hayley described her as Cowper’s literary executor, and it was she who authorised the biography, the editing of Cowper’s Homer and Johnny’s later edition of Cowper’s poems. One feels quite sorry for Johnny, newly ordained and far outranked by Lady Hesketh. She bullied him regularly over what to send and where, even almost two years after Cowper had died. As Hayley’s researcher on the biography, he was again at her beck and call. All this is evident from the many unpublished letters between Johnny and Lady Hesketh, held by the museum, and there are snippets from them in Mary Barham Johnson’s unpublished manuscript.

Extracts

From Catharine Mary Johnson, Cowper’s Norfolk Connections (unpublished manuscript and part of the Barham Johnson bequest, 1998. She was Miss Barham Johnson, great – granddaughter of Johnny Johnson, and owner of his letters and many others.)

As Cowper had not made a Will, Lady Hesketh was appointed Administrix and quickly got to work. Her first thought was for Miss Perowne, who without knowing Cowper’s better days had served him so devotedly [after his move to Norfolk]. She sent her £50 and a muff and mittens, and later arranged for £200 to be allotted to her. But she was not so generous to Johnny, who had to pay £55 for the books, and £28 for linen and plate However she changed her mind so many times as to what should be sent to Cowper’s friends that a good many relics are still in the Johnson family. (p.159)

From Letters of Lady Hesketh concerning William Cowper, ed. Catharine Bodham Johnson, 1901

Postscript to a letter from Bath, Tuesday 29 April to John Johnson

Tho’ our dearest Cousin’s unhappy Situation made it Impossible to suggest to him the idea of a Will – yet when all expenses are settled and the requisite ceremonys are over I shall then hope to be able to desire Miss Perown’s acceptance of some Present such as he would I am sure have wished to have done had he been able to have Expressed his Gratitude for the Kind Care – you dear Johnny must direct me on this Head. By the way surely Mr Rose will voluntarily come forward with a statement of the affairs in which he is concerned. (p.104)

And on the same page, either a separate letter or a continuation of the previous one:

MY EXCELLENT FRIEND

I read your letter over various times and could only wonder every time with increased surprise, how it was possible for you my good Johnny, even for you, to attend to such an endless variety of circumstances and to order and dispose (in spite of your poor halfbroken heart) everything in a manner so proper and so perfectly pleasing to me and to everybody …

I must now observe that as our dear Friend made no Will whatever he may have left behind him goes to his heirs at Law – of which there are nine on your side and ours – on ours there is the Bishop of Peterborough – Mrs Maitland wife to general Maitland – the Dowager lady Walsingham, Lady Croft – my sister Miss Theodora Cowper and myself – now it is my earnest wish that the Bishop – Lady Walsingham and Mrs Maitland should after the Division or before it renounce their shares as I shall certainly do mine, in favour of the rest – of which there are three in your family my good friend, viz Mrs Ball, Mrs Bodham, and some Gentleman you named to Mr Hill – those you see together make Nine, and I fear when all demands are paid our dear Cousin’s assets will afford a small share for each…

(The letter goes on to talk about returning Cowper’s watch to Theadora.)

You are right my Good Friend in your intention to make an inventory of all the trifles that may have belonged to this dear Creature, they are Relics and must be distributed as such to those who will value them for his Sake

Yr much obliged and affect. Well wisher H Hesketh

(The editor adds a footnote, p.106, to say that Dr Johnson bought the books for £55 and the plate and linen.)

On 19 September 1800, Lady Hesketh writes to Johnny to confirm that he ‘may be the Editor of Homer without delay’, and to report that Joseph Hill agrees that ‘Johnny should be given the first edition in Octavo of a Thousand Copys’ retaining the copyright, but subject to Johnny obtaining the approval of the Bishop of Peterborough and, through him, the other branches of the family. Lady H then confirms that she has a letter from the Bishop confirming his approval.

Later letters in 1801 and 1802 have frequent references to items that Lady H wants to send to acquaintances.

1802 Jan 3rd What are the trifles of our dear Cousin’s personals that you desired to have? I think it was the sleeve buttons and something else. By the way there was a pair of sleeve buttons which were my dear Father’s – bloodstone set in gold – I should wish had been forthcoming – as they are not I conclude he had given them away. My sister Lady Croft brought them to my father from Paris … And now dear Johnny there is one thing which I long extremely to have for my own Self. I mean a certain light tall India Stick … which I hope is still in your possession.

The will is available from www.discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D342601

** For further insight into Cowper’s time at the Inner Temple read ‘William Cowper of the Inner Temple’ by Clare Rider, The Cowper and Newton Journal, vol 9, 2019.