Here we focus on a nineteenth-century lace bobbin. Or at least, we’ll start with one bobbin and then look at a few others. This will allow us to peep at the varied work – sometimes fancy, sometimes very basic – coaxed into being by the requirements of this simple lacemaking tool.

We’ll be looking at examples made for nineteenth-century East Midlands cottage workers, as represented in the collection of the Cowper & Newton Museum in Olney. The town played a central role in bobbin lacemaking in the region, from its introduction in the sixteenth century, from mainland Europe, through to its heyday in the Georgian and Victorian periods. William Cowper, when he lived at Orchard Side, Olney (between 1768 and 1786) commented on the privations of the local lacemakers – many of them lived just round the corner from the museum – so we’ll also look briefly at what so concerned him.

But we begin with a brief general note about bobbins and lacemaking in the Olney area.

Lacemaking bobbins

In lacemaking the bobbin is a tool for carrying the thread. The thread – usually cotton, linen or silk – gradually uncoils from a bobbin as it is handled. It will then be woven, twisted, plaited, or in some other way interlocked with neighbouring threads so as to form a delicate ‘lacy’ structure.

A bobbin is also a handle – it’s the means by which a lacemaker can manipulate threads without touching them and potentially dirtying them.

The basic form of most lace bobbins is a narrow cylinder. They are usually about ten cm. (four in.) long and made of wood or bone. In the English East Midlands however any uniformity tends to end there. For this region has a particularly individual and decorative tradition of bobbin making. Bobbins made here vary considerably in design detail; indeed, it would not be unusual for an Olney lacemaker’s pillow to carry well over one hundred bobbins, none of them alike. Continental bobbins tend to be plainer and look very similar to each other, as do those used by Honiton lacemakers in Devon.

The East Midlands is particularly associated with two important kinds of bobbin lace: Bucks Point (typically a fine net lace inset with small decorative motifs) and Bedfordshire (generally a more organic-looking, floral lace). And it is the bobbins used to make these laces which have the carved and ornamented shafts, as well as the brightly coloured beaded ‘tails’, exemplified in the object we examine here. Let us look at this bobbin more closely.

Parts of a bobbin

Our bobbin is made of animal bone – supplied often by the local butcher – and dates from around the mid-nineteenth century. It would have been more expensive than a wooden one, and was probably made by a professional bobbin maker and sold for cash.

It has three main elements: a head and neck (where the thread will be attached); a main shaft, or shank (held by the lacemaker) and a tail end strung with beads.

The head and neck

Let’s consider the thread-bearing end of the bobbin first. Towards the top end of our bobbin the shaft has been carved away to leave an even thinner cylinder – the ‘long neck’. It’s about two cm. (three-quarters of an inch) long. A long length of thread will be wound this long neck and stored there, just gradually unwinding as lacemaking progresses. This stored thread is held in place by a slightly bulbous knop (small knob), at one end of the long neck (it is the start of the bobbin’s ‘head’) and by the thicker main shank at the other end.

Let’s consider the thread-bearing end of the bobbin first. Towards the top end of our bobbin the shaft has been carved away to leave an even thinner cylinder – the ‘long neck’. It’s about two cm. (three-quarters of an inch) long. A long length of thread will be wound this long neck and stored there, just gradually unwinding as lacemaking progresses. This stored thread is held in place by a slightly bulbous knop (small knob), at one end of the long neck (it is the start of the bobbin’s ‘head’) and by the thicker main shank at the other end.

In practice, long necks vary somewhat in length; ours is rather a short one! Longer necks could carry more thread, which was useful when either a thicker thread was involved or if a bobbin was being deployed as a ‘worker’. Worker bobbins act like shuttles: they move over and under the other warp-bearing bobbins. The latter, the majority, are called ‘passives’ since they just ‘hang about’ for much of the time, a role that leads them to require much less thread.

Immediately above the knop there is a little recess (the ‘short neck’) round which the working end of the stored thread is hooked and gradually unwinds. It is important that the head of a bobbin is not chipped or broken – if it is, a working thread will easily slip off. The head of our bobbin is intact, so its thread-bearing element looks to be quite sound.

Lace patterns

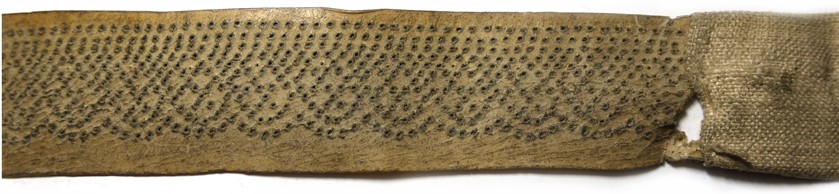

A lacemaker’s work was guided by patterns. These were made from a strip of stiffened material such as parchment and attached to the worker’s pillow. A design for the lace (perhaps to become a thin edging for a cuff or for a handkerchief) would have been drawn onto this parchment and marked with dots for pins.

The dots would be ‘pricked out’ as the lacemaker’s pins were inserted into the pattern bit by bit. A lacemaker’s pins were used to support the hanging warp threads (the passives) which were twisted round them, two by two, so as to achieve the particular arrangement that the ‘worker’ bobbins needed to weave across. After working the pins, a lacemaker would gradually (after an inch/centimetre or so) remove them to free the wrought lace from their hold and would then usually insert these same pins into the next section of the pattern.

The tail

The tail end of a bobbin also has a role to play. As you can see, our bobbin is hung with nine glass beads, called ‘spangles’. There are two pairs each of brown round beads and of slightly smaller, square cut beads of clear glass. At the centre of this assembly there is a larger, Venetian enamelled bead. It is usual to find nine beads spangling an East Midlands bobbin; they might come in different colours to those we see here, but usually form a combination of this sort – that is, a balanced mixture of large and small, round and square beads, with one magnificent centrepiece.

Most beads will – as here – be strung onto brass wire, whose ends are first threaded through the body of the bobbin and then back up through a bead or two for fixing.

Spangles like these are not just a colourful extra. Their most important job is to add weight. This encourages bobbins to hang down, straight and taut, on a lacemaker’s pillow and form a well tensioned warp. A loop of spangled beads also tends to lie flat on a pillow, which helps stop bobbins rolling about a lot and losing their proper place in the sequence of work. The square-cut beads are particularly effective here as their flat surfaces would grip a pillow cloth more firmly than round beads; they were specially made for the lace industry.

By tradition they came in red or white glass and a bead-maker would often enhance the grip factor by roughening their surfaces with a file – pressing it into each side in turn while the glass was still hot.

By tradition they came in red or white glass and a bead-maker would often enhance the grip factor by roughening their surfaces with a file – pressing it into each side in turn while the glass was still hot.

Cut beads were more expensive than round ones and not all lacemakers could afford them. To give a flavour of costs: a bead cost around four old pennies in the 1870s, and might be compared with a lacemaker’s weekly earnings of between three and nine shillings (36 – 108 old pennies). Since a lacemaker might use hundreds of bobbins on a large piece of work, several hundred beads might be involved, which could eat deeply into this wage.

But bobbins might be sold with or without spangles, and one common way of lowering the cost was to buy them un-spangled along with a penny necklace at a local fair; these beads could then be wired on at home. Some lacemakers would combine beads with memorabilia, such as a button, a coin or a shell to add personal meaning to their bobbins. And of course, many bobbins were gifts, not just from family and sweethearts but, and out of commercial interest, from a lace dealer keen to win a good lacemaker’s favours in a competing field.

The shank: ‘KIS ME QUICK MY MOME IS COMIN’

Let us turn now to the main shaft of our bobbin, for this is where decoration can become really individual. Ours is inscribed with the words, ‘Kis me quick my mome is comin’ – the letters formed from dots drilled into the bone and filled with red ink.

Inscribed bobbins, in both wood and bone, are not unusual. The simplest and most common bear Christian names, usually female, generally made from dots coloured red, black or blue. Wooden bobbins usually stop there. But bone ones tended to be more elaborate: sometimes a surname is added and sometimes the prefix ‘Dear’, ‘Sweet’ or ‘Lovely’. This romantic strain might be played out even more loudly with words such as ‘to my love’ or ‘love be true’ or ‘love don’t be falce’. Our wording is just a rather saucier version in this tradition and there were many others like it.

The practice of inscribing bobbins with words that advertised (a politician seeking election), commemorated (a national event), moralised (bible quotations) or otherwise appealed to souvenir hunters, developed into quite a profitable business. One particularly striking example of this successful commercialisation is the so-called ‘hanging bobbin’. These became very popular souvenirs. The museum’s example commemorates the last public hanging at Bedford gaol. It reads ‘W.WORSLEY. HUNG 1868’ and is probably the most common of the six known hanging bobbins, all of them connected with events in the East Midlands. Worsley was hanged for the murder of William Bradley in Luton on the evidence of his accomplice Levi Welch. The latter escaped the gallows by ‘turning Kings Evidence’, but was convicted of robbing Bradley’s body and given 14 years penal servitude.

Another museum example, with an inscription of even closer local interest, reads ‘Jack Alive’. The story accompanying this bobbin is of an illiterate lacemaker who lived at Lavendon – a village just a mile or so away from Olney. Jack, her son, was a sailor, and wherever he went in the world he would have a bobbin made for his mother, and send it to her. She knew he was alive when she received it

The trade in making bobbins, and their variety

Bobbin making was just one of the spin-off trades that benefited from a thriving lace industry in the nineteenth century. Others include carpentry (for making the ‘horses’ – the wooden stands – that support lace pillows), bead making (as we have already seen), pillow making (pillows were stiffly stuffed with straw and covered with a cotton or linen cloth) and of course lace dealing. Most of these trades were male. Bobbin makers were nearly always so, but their work, and that of the predominantly female lacemakers, remains largely anonymous.

Just occasionally we can identify the work of a particular bobbin maker, through a notable family tradition or a distinctive characteristic, such as particularly bold or delicate lettering, or some idiosyncratic arrangement of letters. Such recognition is even rarer when it comes to the lacemakers: there was little personal creativity involved in their daily piece-work, which usually involved making lace to order and to patterns designed by someone else.

We have concentrated so far on bone examples, but bobbins turned or carved from wood might also be made by professionals. Fruitwoods such as cherry or plum were the most popular, whether drilled and named, or left plain. And alongside this professional work there were also many wooden bobbins whittled into shape by amateurs, who gave their whittlings to a lacemaker out of friendship. These, though often simpler in appearance, are full of charm and character, evoking as they do reflections on the amiable and sometimes romantic contexts in which such gifts were wrought.

The two wooden bobbins below are professionally made.

It is perhaps worth noting that the tools used to make even the finest bobbins in the nineteenth century were fairly crude by today’s standards. Bobbin makers used hacksaws to cut into their chosen wood or bone, before turning it on a treadle lathe and finally applying a small drill to make the spangle-hole and dots for any lettering. Hand-carved, decorative effects, such as rows of rings, diamonds, or squares which stood proud of the basic material, were made with knives; as were the more complex carved ‘windows’ – deep grooves in the shaft, that sometimes enclosed a row of tiny balls (‘church windows’) or sometimes another miniature bobbin (‘mother-in-babe’).

Decorative metal inlays – usually pewter – were also used to create a sparkling effect. This was achieved by cutting grooves of the appropriate shape (stylised butterflies were popular, or stripes to make the so-called ‘tigers’, or spots to make the ‘leopards’) and then pouring in molten metal.

Such metal additions – brass wire was also used – would add to the brightness of a bobbin, for they could gather quite a shine with constant turning and rubbing.

Wooden bobbins might also be inlaid with other woods – often a dark body was inlaid with a lighter one – to form spirals, stripes or even dramatic geometrics. These were the so-called ‘bitted’ or ‘bitten’ bobbins. Bobbin-making was quite a business and one that tended to be passed down through a family.

The eighteenth century – what Cowper saw

What Cowper saw is interesting, less for the insights it gives us into bobbin making specifically, more for a general sense of a dominating trade – the crucial part played by the lace industry within Olney. But he also gives us a particular sense of the vulnerability of the lacemakers: to fashion, to politics, to those with the money to employ them as well as to the tedium and parlous conditions of the work itself.

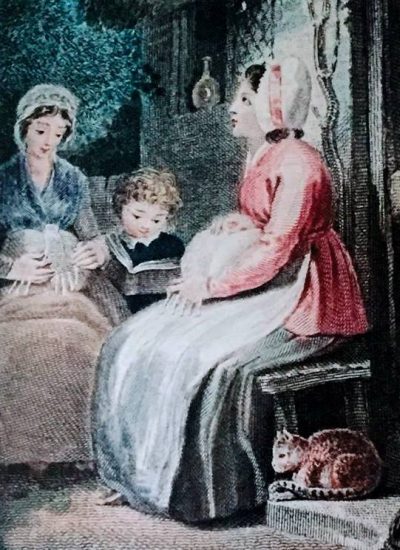

Even before Cowper came to Olney – from the sixteenth century onwards when bobbin lacemaking was introduced here – we find references to lacemaking which emphasise the poverty of its workers or allude to its association with ‘the poor’, for example, workhouse children being taught ‘bone lace’ so as to earn something towards their keep. This practice was supervised by the Overseers of the Poor who would pay an experienced lacemaker to instruct the children. It developed, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, into lace schools of some renown, established in Olney and throughout the Ouse Valley villages.

But – and perhaps rather curiously given these associations – ‘point ground’ lacemaking (lace made in the Buckinghamshire tradition) was not restricted to the poor; in the eighteenth century it was also made by many aristocratic women. The occupation was considered an elegant and appropriate pastime for ladies, along with many other fine needlework crafts. Indeed it became fashionable for such women to send their daughters to France on lacemaking apprenticeships as part of their ‘finishing’.

But work for a commercial lacemaker in Cowper’s day was quite a different thing. It was on the whole tedious (being very repetitive), ill paid and often carried out in difficult, not to say miserable, conditions. Light and heat were minimal and the work was entirely sedentary – ‘just sitting’ at a lace-pillow, working the bobbins. Eighteenth-century observers tend to make much of the consequent pallor and lassitude of lacemakers. Even as late as 1779, the traveller Thomas Pennant remarked with reference to Newport Pagnell, another lacemaking centre and market town five miles from Olney:

It flourishes greatly, by means of the lace-manufacture, which we stole from the Flemings, and introduced with such success into this county. There is scarcely a door to be seen, during Summer, in most of the towns, but what is occupied by some industrious pale-faced lass; their sedentary trade forbidding the rose to bloom in their sickly cheeks.

Although many towns and villages like Olney and Newport Pagnell were sustained by the lace industry throughout the eighteenth century, the trade was subject to recessions and, unlike the dealers, the lacemakers themselves did not prosper from it; they merely survived.

Cowper, when he lived in Olney, commented in some detail on the poverty of the area and its lacemakers. This became more acute in the 1780s – a particularly difficult time for lacemaking in England due to competition from abroad as well as the caprices of fashion.

Nevertheless, in his poem Truth, Cowper summed up local lacemaking life in somewhat pastoral vein – tough but with its benign side and definitely ‘possible’:

Yon cottager who weaves at her own door,

Pillow and bobbins all her little store;

Content, though mean, and cheerful if not gay;

Shuffling her threads about the live-long day;

Just earns a scanty pittance, and at night

Lies down secure, her heart and pocket light.

It is his letters which give life to this rather generalised picture; they give us glimpses of how life was actually lived by the lacemakers, a far more gritty reality.

For a start we learn that Olney was

… a populous place, inhabited chiefly by the half-starved and the ragged of the earth…

But Cowper does not always focus on lacemakers’ poverty, he is more interesting than that. For example, in 1781 he wrote to Newton:

Olney has seen this day what it never saw before, and what will serve it to talk of I suppose for years to come. At eleven o’clock this morning a party of soldiers entered the town, driving before them another party, who after obstinately defending the bridge for some time were obliged to quit it and run. They ran in very good order, frequently faced about and fired, but were at last obliged to surrender prisoners of war. There has been much drumming and shouting, much scampering about in the dirt, but not an inch of lace made in the town, at least at the Silver End of it.

This wry reference to Silver End is to the little road round the corner from Cowper’s home, where many lacemakers lived, and with whom he rather unwillingly shared some of its features. Another letter to Newton, written that same year, again dwells on the squalor of Silver End. He is rhapsodising about the greenhouse he had built in his garden at Orchard Side:

…here we spend all the rest of our time, and find that the sound of the wind in the trees, and the singing of birds, are much more agreeable to our ears than the incessant barking of dogs and screaming of children, not to mention the exchange of a sweet-smelling garden for the putrid exhalations of Silver End.

Cowper was clearly more approving of – or at least less affected by – the local lace dealers. They belonged to Olney’s minority – to the well-off and respectable. We pick up his sense of them from a letter written to his cousin Lady Hesketh, for whom he has been seeking rooms to rent:

The rooms that you will occupy are all well sashed; the parlor window and the chamber are both [with] Venetian [blinds]. The people themselves are very honest, sober, elderly folks, and quite respectable. They carry on a trade, but a very neat and silent one – they are dealers in lace.

But his concern for the poverty-stricken lacemakers themselves was real enough. In the years when legislation protected the local trade (it restricted the import of foreign lace – for instance there were heavy duties imposed on French-made lace) times were not so bad. But these favourable conditions did not last. In 1780 the local lacemakers’ survival was threatened by an Irish demand for free trade. A bill came before Parliament which sought to remove tariffs imposed on many Irish goods – including lace. Cowper took action on the local lacemakers’ behalf. He petitioned Lord Dartmouth (a patron of the Reverend John Newton and another fervent Evangelical) to speak against the removal of such a tariff. He was

…praying him to interfere in Parliament, in behalf of the poor lacemakers

And Cowper went further. He commended the same petition to his friend Joseph Hill, who ‘had the ear’ of the Lord Chancellor. In a letter to Joseph, he emphasised the dire straits in which local lacemakers found themselves and his fear for their future should any bill of this sort be successful:

If you ever take the tip of the chancellor’s ear between your finger and thumb, you can hardly improve the opportunity to better purpose, than if you should whisper into it the voice of compassion and lenity to the lacemakers. I am eye-witness to their poverty, and do know that hundreds in this little town are upon the point of starving, and that the most unremitting industry is but barely sufficient to keep them from it. I know that the bill by which they would have been so fatally affected, is thrown out but Lord Stormont threatens them with another; and if another like it should pass, they are undone. We lately sent a petition to Lord Dartmouth; I signed it and am sure the contents are true. The purport of it was to inform him, that there are very near one thousand two hundred lacemakers in this beggarly town, the most of whom had reason enough, when the bill was in agitation, to look upon every loaf they bought as the last they should ever be able to earn… The measure is like a scythe, and the poor lacemakers are the sickly crop that trembles before the edge of it. The prospect of peace with America is like the streak of dawn in their horizon, but this bill is like a black cloud behind it, that threatens their hope of a comfortable day with utter extinction.

Cowper also used his position to help the lacemaking poor of Olney financially and with material resources. He was assisted in this by the generosity of the philanthropist Robert Smith (a wealthy Nottingham banker, later Lord Carrington). Smith occasionally provided him with funds to administer as he felt most appropriate.

Cowper reported in 1782:

We shall use our best discretion in the disposal of the money… We promise however that none shall touch it but such as are miserably poor, yet at the same time industrious and honest, two characters frequently found here where the most watchful and unremitting labour will hardly procure them bread.

Cowper went on to illustrate the gratitude of a lacemaker whom he had been able to help by telling this story:

One woman carried home two pair of blankets, a pair for herself and husband, and a pair for her six children. As soon as the children saw them, they jumped out of their straw, caught them in their arms, kissed them, blessed them, and danced for joy.

Bobbin making and lacemaking today

It is a long step from Cowper’s days to the present, when lacemaking survives largely as a hobby. For the craft definitely continues but it is carried out mostly by small groups of female lacemakers interested both in the tradition and in its modern potential.

And bobbin making? Well, there are also many modern bobbin makers, and fortunately for them, many collectors. This side of the trade flourishes through magazines and textile fairs. Many men and women make a living by producing delightfully painted bobbins, usually painted bone or modern resin. And there are some wonderful turned examples in unusual woods.

Bobbins are still bought for use but many are also targeted at collectors. Bobbin makers market them cunningly in vast themed ‘collections’, which relentlessly capture their audience as well as delight. This part of the trade has not lost its business edge.

Further Reading:

For the history of lacemaking in Olney and the East Midlands counties of Bucks, Beds and Northants, see our Lacemaking Blog article

Hopkins,D, Lacemakers and Old Songs, in Olney and Elsewhere, Cowper & Newton Journal, Vol 5

Wright, T, The romance of the lace pillow; being the history of lace-making in Bucks, Beds, Northants and neighbouring counties, together with some account of the lace industries of Devon and Ireland, 1919

The website of The Lace Guild

The rules for the Workhouse in Olney can be found in An Account of Several Work-houses for Employing and Maintaining the Poor: Setting Forth the Rules by which They are Governed

Bartlett, Liz, Lace Villages, Batsford, 1991