Here we focus on a few small items of dress, carefully chosen by Cowper to present himself creditably to the world.

We begin with a buckle Cowper used to pin a fine linen neckcloth (called a stock) firmly round his neck. These were definitely part of a gentleman’s attire, and helped to define you as a person of taste and high status. It is perhaps a little surprising to learn that the buckle itself – despite being sometimes beautifully crafted, and almost jewel-like, was not often displayed. It was fixed at the back of the neck to fasten the stiff folds of the stock. Moreover, it was fashionable in Cowper’s day to tie further linen material, in extravagant-looking bows, to the front of the neck, and these covered much of the stock itself.

Neck attire was a serious and complicated business, and Cowper went to some trouble to acquire both the linen for the stock and a fine buckle, despite his straitened circumstances.

Keeping in mind this eagerness to present himself to best advantage, we will also take a look at some of the other fashionable items Cowper felt it necessary to purchase, and will consider how and why this might have been.

The stock buckle

The frame of Cowper’s stock buckle forms a rectangle. It is made of silver and the front has been decoratively tooled to show stylized acanthus leaves. Inset within this rectangular frame is a plain brass bar; there is a small brass bracket over this simple bar ornamenting and bridging its length. The bar swivels and has two important elements swinging from its centre; they are there to fix the stock (a kind of neck-tie) in place. From one side there swings another bar, set with three small ‘buttons’ or tabs; these protrude beyond the silver framework and function to hold one end of a stock in place: they attach to holes – cut and sewn like button-holes – found at one end of a stock.

From the other side of the central brass bar protrude three fork-like prongs. These are used to pierce the other end of a stock – where the fabric is usually gathered and sewn into a tight point.

The prongs and the button-like tabs together hold a stock in place, wound neatly round the wearer’s neck.

A stock was a relatively formal item of neckwear that became fashionable in the eighteenth century. It was a more constructed and fancier version of a neckcloth or a neck handkerchief.

Throughout the century it was usual for men of all classes to wear one of these three kinds of neck attire when in public – whether labouring, or attending some fashionable gathering. The distinctions between them are small but for the fashion conscious and socially aware they were significant.

A neck handkerchief or neck kerchief (more common at this time than the pocket handkerchief) might be worn by men or women. It was the least formal choice of neckwear. Women tended to wear it loosely wrapped round the neck, fixed with a pin, a knot, or some other fancy tie. Men usually rolled the kerchief before pinning or tying it at the front; the ends being then left free to hang down quite casually.

A neckcloth was only slightly different. It was a rectangular length of fabric worn by men, first rolled, then wrapped round the neck and tied loosely at the front. A neckcloth might be worn over a shirt collar so as to cover it completely, or with the ends of the collar folded down over it. Neckcloths varied in grandeur, partly depending on the fabric used, but they were in any event considered more formal than handkerchiefs. Some were quite plain, others embellished with frills, knots or lace at their ends; these ends hung down, rather flamboyantly, at the front of a shirt. A trimming of lace was particularly fashionable at the start of the century (when lace itself was very popular) but considered rather commonplace by the 1770s.

A stock was the grandest of these three kinds of neckwear. It was made of delicate material, often the very finest linen, whilst kerchief and neckcloth were usually of rather coarser fabric. The drawing above shows Cowper wearing his stock, and the linen cap that we shall come to later.

The main section of a stock – the part on show – was finely pleated, or gently gathered into a longish sausage-shape, often backed with a plainer and heavier material. The ends of a stock did not quite meet round a wearer’s neck – that is where the buckle came in. One end would be fitted with small loops or button-holes attached to a stronger material. These would loop onto the ‘buttons’ of a stock buckle. The fabric at the other end of a stock would be sewn into a point and cinched into place with the prongs of the stock buckle. So the fabric went round the neck and the stock buckle held everything together at the back.

But key to the impact of any of this neckwear was its cleanliness. The best neckcloths were white – very white. It is worth recalling perhaps that a decent appearance in the eighteenth century called for freshly laundered linen every day. One on and one in the wash, as the saying goes; or for the more wealthy, seven shirts and one laundry day a week. Clean linen signalled a wearer’s self-respect by referring obliquely to the hours of steaming and honest labour it demanded.

Cowper and fashion

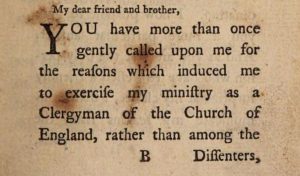

It was in 1781 that Cowper resolved to start wearing a stock rather than a ‘neck cloth’. We learn this from a letter he wrote to his friend William Unwin, in which he asked him to buy the all-important stock buckle with which to hold the stock in place. In some respects he was quite particular about this buckle, but interestingly was at the same time happy for it to be second-hand. (Mrs Unwin also thought second-hand goods quite acceptable – for example a silver cream pot in 1784.) But here is Cowper registering his shift in neckwear and need tor a buckle:

‘My neck cloths all being worn out, I intend to wear stocks, but NOT unless they are more fashionable than the former. In that case I shall be obliged to you if you will buy me a handsome stock buckle for a very little money; for 20 or 25 shillings perhaps, a second hand affair may be purchased that will make a figure at Olney.’

It is quite hard to work out how serious Cowper was about looking fashionable; he was clearly teasing himself (and Unwin) about ‘cutting a figure’ in poverty stricken, rural Olney with a purchase he insisted should be modest as well as ‘handsome’. And he had, a week or so earlier, written at length, wryly and with evident tongue in cheek, about ‘fashion’ to Mrs Newton (the Revd John’s wife). Talking of his uncle:

‘He trembles on the verge of fourscore. A white hat with a yellow lining is no indication of wisdom suitable to so great an age…He is a very little man, and had he lined his hat with pink instead of yellow, might have been gathered by a natural mistake for a mushroom and sent off in a basket.

While the world lasts fashion will continue to lead it by the nose. And after all what can fashion do for its most obsequious followers? It can ring the changes upon the same things and it can do no more. Whether our hats be white or black, our caps high or low, whether we wear two watches or one, is of little consequence.’

In practice, Cowper seems to have been more concerned to keep up with contemporary fashion than he cares to admit here. And this seems to have been particularly true when it came to his personal attire. It patently mattered to him that he looked ‘right’. Right, in the sense of presenting an appropriate image as well as an authentic one. Cowper’s self-portrayal did not focus on demonstrating wealth (hard to do anyway as he had little money) or social standing (which he was inclined to mock), though it might hint at an acquaintance with such things. ‘Looking right’ and ‘dressing right’ referred more to contemporary ideas of ‘taste’. Good taste was connected with and, in the case of apparel, expressed, important moral values including modesty and decency. It also comprehended humane and educated qualities such as sensibility, discrimination and refinement.

Cowper seems to have thought that these were learned rather than inherited. To William Unwin in 1782, reflecting on a child’s development, he wrote:

‘It is not in general till reading and observation have settled the taste that…we are able to execute what is good in ourselves.’

In a later letter to William (having mentioned our ancestors’ strange preference for ‘the slashed sleeve’ or the ‘trunk hose’) Cowper went on to muse:

‘…in everything else I suppose they were our counterparts exactly…The inside of the man has undergone no change, his passions, appetites and aims are just what they ever were: they wear perhaps a handsomer disguise than they did in the days of yore, for philosophy and literature will have their effect upon the exterior, but in every other respect, a modern is only an ancient in disguise’

So it is perhaps in the guise of an educated ancient that we discover Cowper, in so many of his letters, ordering dress fabrics and personal accessories with such precision. His attention to detail suggests that he minded what people thought of the result, and though sometimes his requests sound – to a twenty-first century ear at least – a little extravagant, it is pretty certain that luxurious ostentation was not his goal, for this was a general target for contemporary criticism.

Luxury – something you could really do without – was one thing, and open to moral censure, but Cowper was outraged in 1785 by a tax imposed upon gloves:

‘I feel myself a little angry with a minister who when he imposed a tax upon gloves was not ashamed to call them a luxury. Caps and boots lined with fur are not accounted a luxury in Russia, neither can gloves be reasonably deemed such in a climate sometimes hardly less severe than that. Nature is indeed content with little, and luxury seems in some respect rather relative than of fixed construction.’

So what are we to make of the shift to a stock? Was it just a desire for a change? Was Cowper really interested in being thought fashionable? Or was there something else about the look of a stock that appealed to him?

Let’s have a look at some other purchases destined for Cowper’s dressing room and see if there is anything common to them all.

A ruffled Cowper

We’ll start with a letter of January 1771, that Cowper wrote to Joseph Hill, a London friend who managed his financial affairs. In it Cowper mentioned TWO tailors’ bills. To his relief, he was not overspent on this occasion and so was able to put in an order for handkerchiefs and fabric.

‘I…am glad to find that after payment of my two taylors, there is a surplus left. I should be glad to have ten pounds sent hither in a note. The remainder I purpose to dispose of in the purchase of a dozen and a half, red and white, small patterns handkerchiefs at half a crown apiece [12.5 modern pence] and a yard and a half narrow striped muslin for a gentleman’s ruffles. If either of your sisters should chuse a walk…I shall be glad of her assistance to procure them for me.’

We might note in passing that Cowper seems to think that women, rather than men, had the appropriate eye (or knowledge) for purchasing such things as the ‘right’ fabric. The letter was written some years before the women in Cowper’s life apparently got wind of his taste for ruffles. By the 1780s Cowper and ruffles were clearly an item, and it seems unlikely that he would ever need to purchase them again: ‘his women’ produced them for him. They appear almost as the modern equivalent of a pair of socks or a tie – a seemly gift to a man from a woman. Cowper received several.

But before we go into this, what were these ruffles exactly?

A costume accessory, they were made from short lengths of fine material – muslin, lace or a delicate cotton lawn – gathered into fullish flounces and worn at the end of a shirt-sleeve. The gathered fabric draped elegantly over wrist and hand and added a graceful flourish to polite arm and wrist movements. They were an extension and embellishment of a plain shirt-cuff as well as a bit of body theatre. They probably even contributed a certain elegance to snuff-taking – and Cowper was a keen snuff-taker. Ruffles were definitely a fashionable rather than a necessary addition to male attire. And they could have been seen as a luxury, but for the fact they tended to be home-made and thus not an expensive consumer good.

And so to the female ruffle conspiracy.

We know that a Miss Shuttleworth (William Unwin’s sister-in-law) made Cowper a pair which she sent on to him after a brief visit on her way home from ‘the North’. And Cowper’s flamboyant would-be amour, Lady Austen, also made him several pairs. (It seems likely that ruffle-making was another of those needlework crafts which manifested a lady’s practical skill as well as her refinement.) Her beneficence did not go down well. At times Cowper evidently found Lady Austen’s attentions a bit too intrusive and, rather curiously, these times seem to have coincided with gifts of ruffles.

In 1782 for example, Cowper wrote to William Unwin to describe, with evident alarm, Lady Austen’s all-pervading, if exciting presence. He also worried about her penchant for ruffle-giving:

‘She is exceedingly sensible, has great quickness of parts, and an uncommon fluency of expression, but her vivacity was sometimes too much for us; occasionally it might refresh and revive us, but it more frequently exhausted us, neither your mother nor I being in that respect at all a match for her. But after all, it does not entirely depend upon us, whether our former intimacy shall take place again or not, or rather whether we shall attempt to cultivate it, or give it over, as we are most inclined to do, in despair. I suspect a little by her sending the ruffles…’

Just one month earlier Cowper had referred anxiously (again in a letter to William Unwin) to multiple pairs of home-made ruffles presented to him by Lady Austen after a quarrel between them. Their arrival had caused similar perturbation:

‘Having imparted to you an account of the fracas between us and Lady Ann, it is necessary too that you should be made acquainted with every event that bears any relation to that incident. The day before yesterday she sent me…three pair of worked ruffles with advice that I should soon receive a fourth. I knew they were begun before we quarreled…the fear of giving offence to a temper too apt to take it, is … absolutely incompatible with the pleasures of real friendship.’

How effectively this frothy, light-weight accessory could ruffle the equilibrium of those at Orchard Side!

And ruffles were clearly social fripperies. Although Cowper must have thought they were a good idea when he ordered material for a pair back in 1771, it is not obvious how this accessory related to ideas of modesty and decency in dress. Perhaps the fact that ruffles were home-made, rather than purchased as a finished consumer item, lent them a homespun virtue. Perhaps, too, they expressed that part of Cowper that enjoyed playing the part of elegant entertainer and witty companion.

Cowper hatted…

So, let’s now move up to Cowper’s head – for he tells us quite a bit about his hats and wigs. Head attire was complicated in the eighteenth century – for both men and women – and it could be expensive. Cowper was attentive to its demands too, and his purchases suggest he sought a mixture of convenient and necessary headgear as well as relishing an element of the superfluous.

Mrs Unwin also needed a range of caps, hats and bonnets to meet the different demands of mourning, visiting, and walking in bad weather. Cowper undertook to procure them for her, and here he is putting in an order to his cousin Harriot, Lady Hesketh. He asked that the bonnet should be

‘…just the bonnet of all the world that will please the most… a bonnet is not to be procured at Olney. The wind alone confines us when it is brisk as the hat she wears being broad and stiff is so susceptible of all its force, that to keep it on at such times is impossible…’

When asked for a bit more helpful detail, he added:

‘The lady says that she is not fond of black bonnets; the lady likewise says that she is not young, and therefore does not wish for a very airy one. Something decent yet smartish, neither Quakerly nor gay, will exactly suit her.’

The resulting purchase was so successful that

‘Never since it arrived has she crowned herself with any other covering of the kind.’

So ‘decent’ and ‘smart’ were keywords for her ‘look’. Meanwhile, Cowper had exacting demands for himself:

‘And my head will be equally obliged to you for a hat of which I enclose a string that gives you the circumference. The depth of the crown must be four inches and one eighth. Let it not be a round slouch which I abhor, but a smart, well-cocked fashionable affair.’

This order was made in 1784, when the three-sided cocked hat (the tricorne) had gone out of fashion to be replaced by the bicorne – a hat turned up at both sides or just at front and back. Presumably a bicorne was what Cowper required. It seems clear that he wished to be ‘up to date’, but also, and like Mrs Unwin, ‘smart’ in appearance.

Then in 1784 he ordered another hat. Again it was to be a fashionable one – nothing merely plain and warm:

‘I will subjoin the measure of my hat. Let the new one be furnished a la mode…The outside circumference of the hat-crown is two feet one inch and an eighth.’

This sounds enormous – a crown of around 64 cm. Surely there are hints here of Cowper the dedicated follower of fashion.

Cowper’s linen cap

Indoors during the day, unless they were expecting visitors, gentlemen would often wear a cap over their close-cut hair instead of a powdered wig. This fashion, a type of informal attire or ‘undress’, was particularly associated with artists and men of letters. A fine linen cap like the example owned by the museum (above) was also called a ‘nightcap’ and indeed might be worn at night for (meagre) extra warmth.

This cap was given to Cowper by Lady Hesketh. In the poem ‘Gratitude’ he thanks her for it and for other thoughtful gifts, all calculated to add to his ‘chattels of leisure and ease’:

‘This cap that so stately appears

With ribbon-bound tassel on high,

Which seems by the crest that it rears

Ambitious of brushing the sky:

This cap to my cousin I owe,

She gave it, and gave me beside,

Wreathed into an elegant bow,

The ribbon with which it is tied.’

Following the famous portrait by Romney, it has become part of his image, appearing frequently in pictures of him.

How was it made and worn? It was essentially a simple tube of cloth – a square piece of linen with a seam down one side. Usually, it would be closed off by a bow tied to its top, while the other, the open end, would be turned up to form a brim that fitted the brow. In Cowper’s case this basic tube was a little more ‘fashioned’. The side seaming was curved and the linen was folded and more shaped.

…and bewigged

Along with hats, fashions in wigs also changed and we know that Cowper’s – or their fittings at least – did too. And it seems he was partly concerned to please others as well as himself as he ‘progressed’ from one style to another. We get a glimpse of such adjustments when we enter bag wig territory.

‘Bag wigs’ have a bag at the back to hold loose ends of hair. We’ll uncover more about them shortly as we look at Cowper’s shifting tastes in wigwear. He first mentioned this type in a letter to cousin Harriot of late 1785:

‘As for me I am a very smart youth of my years. I am not indeed grown grey so much as I am grown bald. No matter; there was more hair in the world than had ever the honour to belong to me. Accordingly having found just enough to curl a little at my ears, and to intermix with a little of my own that still hangs behind, I appear if you see me in an afternoon, to have a very decent headdress, not easily distinguished from my natural growth; which being worn with a small bag and a black-ribband about my neck, continues to me the charms of my youth, even on the verge of age’.

He mentioned his bag wig again to Harriot in 1786; and explained why he had earlier adopted this style, and has now abandoned it:

‘I promise you that your squire shall not be dressed in a bag. By some instinct in me it has come to pass, that immediately after telling you I wore a bag, I of my own motion exchanged it for a queue. That ever I wore a bag constantly was owing to Lady Austen, who in France had been used to see nothing else.’

There is quite a bit of wig detail to unpick in the last two extracts. ‘The bag’ that Cowper referred to was a black pouch, often made of taffeta, into which the long ends of hair at the back of a wig were stuffed. The bag usually came with long ribbons which would be tied into a bow to keep the bag closed. A bag like this was an important addition: in particular it kept greasy wig hair out of harm’s way as well as tidy. For the hair of a wig was thoroughly oiled before being powdered to help glue the powder on. (The fashionable, light powders of mid- to late century were starch-based – usually rice or wheat flour – and the oils used were often fragranced with lavender or orange water.) It was the oily residue – the powder’s fixative – that was the problem. It stained shirt collars and other neckwear and could easily ruin a good silken jacket.

The ‘queue’ that Cowper said he switched to was popular at the same time as the bagwig. By ‘queue’ he meant the tail (‘queue’ in French) or small plait that the ends of a wig might be tied into. Another very tidy solution for loose back hairs.

Although not unwilling to follow fashion, Cowper was adamant that he would decide on his appearance for himself. His personal purchases, particularly those related to clothing, were part of a kind of determined self-expression or tempered self-fashioning. Or so we are asked to believe.

In 1790, some four years after the bag wigs, Cowper changed his hairstyle again:

‘My periwig is arrived and is the very perfection of all periwigs, having only one fault which is that my head will only go into the first half of it, the other half or upper part of it continuing still unoccupied. My artist [that is, hairdresser] at Olney has however undertaken to make the whole of it tenantable and then I shall be twenty years younger than you have ever seen me.’

It is not obvious what Cowper meant by a ‘periwig’ here. It is possible that he was referring – half- jokingly – to his purchasing a rather more formal item of headwear than was his norm.

If so, perhaps this addition to his wardrobe had something to do with his move to Weston Underwood and his growing friendship with the aristocratic Throckmortons. (The extract above is taken from a letter to Lady Throckmorton.) For wigs by now were worn mostly just by the older generation and the more conservative; they were no longer the height of youthful fashion.

But then eighteenth-century male wigs probably never were much of a conspicuous fashion statement – they were too commonplace and too useful to be regarded as frivolous. As we have just seen, Cowper himself rejoiced in the way a wig could conveniently disguise his age and of course keep his balding pate warm.

We can see from his taste in headwear that Cowper liked to look ‘smart’ and orderly. A stock was clearly ‘smart’, and tidy too. It rounded off the neck neatly and cleanly and made a similarly decent fashion and personal statement. Maybe there is a modest commonality here.

Buttons and shoe buckles

He seems to have been especially fond of buttons. Not just the gold buttons that had belonged to his father – clearly of sentimental as well as monetary value – but new buttons that gave his clothing a distinctive finish.

For example, he wrote to cousin Harriot in 1787:

‘Thanks to your choice I wear the most elegant buttons in all this country; they have been much admired at the Hall. When my waistcoat is made I shall be quite accomplished.’

The museum also owns a few other small accessories which belonged to Cowper, things he carried round with him or wore and which contribute to our picture of him. These include two large metal buttons cut with a star-like motif, and a smart pair of shoe buckles.

As well as the buckle for his stock, Cowper used a pair to fix his shoes firmly to his feet. Shoe buckles had become fashionable in the 1690s, overtaking the fancy bows or ‘roses’ formerly used to cover the straps or ‘latchets’ then in vogue. They were transferable between shoes and allowed the opportunity for decoration. A variety of materials was employed in their making of buckles, including Tutania (a pewter like alloy) and silver (a pair costing between seven and eight pounds). From the 1760s onwards cut steel came to the fore, most commonly from the Wolverhampton area..

But from the start they were found to be troublesome, regularly coming undone or loose, and often at inconvenient times. There is a story told of Cowper’s own pair causing him this sort of nuisance – a tale he, very typically, enjoyed embroidering to entertain friends.Cowper liked to take a daily walk of three or four miles for his health, and one day a shoe buckle became loose and needed adjusting. As he bent down, placing his foot on the step of a stile to fix the problem, a plump village postwoman came along from the other side without Cowper noticing her. She mounted the stile and placed her rather large foot on what she supposed to be the step on the other side. In fact she had managed to tread on what turned out to be the poet’s bald head. Cowper, wondering what was happening, tossed his head up abruptly and, as he did so, up went the old woman too, making, in Cowper’s words ‘a rotatory somersault in the air’. Profuse apologies on each side of course, but Cowper made much of the accident, in particular regaling his friends the Throckmortons at Weston Hall with the story.

Not surprisingly perhaps, the fashion for shoe buckles was not to last, and by 1790 had given way to shoe-ties.

Conclusion

Finally, for an affectionate word picture of the poet’s ensemble as he prepares to set forth on his daily walk, let us turn to Johnny Johnson. Cowper’s young cousin describes the clothes and accessories being laid out for him:

… the walking shoes his valet bore

And what were buskins termed in days of yore,

Short, and of black material meant to sheathe

From dirt the speckled honours underneath:

The wig, whose name verse hesitates to tell,

An incanorous [unmelodious] monosyllable;

The brown surtout [overcoat] with velvet collar matched

Though a poet’s garment, nowhere patched,

The hat and gloves; and fitted to one hand,

Rough-coated as it grew; the hazel wand –

All these into his study brought.

Quite a mixture.

His choices span a considerable range – from the seriously fine stock and finer stock buckles, to those smart wigs and rather cocky hats; and from flouncing ruffles, fancy buttons, and delicate and expensive fabrics, right down to the sensible shoes and ‘buskins’ (probably in this context a type of gaiters) he donned for walks. He is practical, smart, tidy and decent – orderly with a twist.

As so often where Cowper is concerned there is a tension. In his choice of apparel and accessories he displays a modern desire for authentic self-expression, but one limited by the constraints of a modest income and the cultural proprieties of his time.

Further reading

Calthrop, Dion Clayton, English Costume 1066-1820, A & C Black, 1923.

King, James, and Ryskamp, Charles (eds.), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 5 vols, 1979-86). All quotations from Cowper’s letters are taken from this edition.

Lowes, Emily Leigh, Chats on Old Lace and Needlework, T. Fisher Unwin, 1908.

Swain, Margaret, Historical Needlework. A Study of Influences in Scotland and Northern England, Barrie and Jenkins, 1970.

Wright, Thomas, The Romance of the Shoe, C.J. Farncombe & Sons Ltd, 1922.

Past Pleasures Ltd, Ahead by a Neck

Romney, George; Dr John Matthews; Tate; www.artuk.org/artworks/dr-john-matthews-201544

Art of the wigmaker, containing the style of the beard; haircut; the construction of men’s and women’s wigs; the old wigmaker, and the steamer bather, by M. de Garsault, Desaint & Saillant , 1767