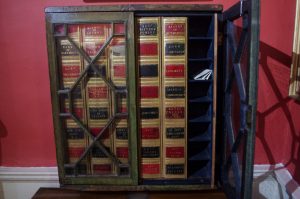

The most detailed account of Cowper’s pet hares is contained in a letter he sent to The Gentleman’s Magazine. It was published in the June 1784 issue, and listed rather prosaically on the contents page as ‘Unnoticed properties of the Hare’. (In the same issue is a description of ‘Experiments on various Air Balloons’, another topic that fascinated Cowper.)

Cowper was a regular reader of the magazine, a glorious miscellany of politics, current affairs, nature notes, travel writing, poems, descriptions of antiquarian discoveries – in fact anything and everything that might be of interest to its ‘gentlemanly’ audience. It relied heavily on contributions sent in from all over the country to ‘Sylvanus Urban’, the pseudonym of John Nichols, its editor, author and publisher.

The letter explains how he came by his hares, and how he reared them, before describing their individual characters and diet. His affectionate and scrupulously detailed examination of their habits gives us a vivid sense of the sort of pets they can make.

This little masterpiece has attracted much interest and admiration over the years. Here is the nineteenth-century philosopher J.S.Mill, for example, reflecting on his own literary education:

Cowper’s short poems I read with some pleasure, but never got into the longer ones; and nothing in the two volumes interested me like the prose account of his three hares.

Note Cowper’s mention of ‘Puss’ in the first paragraph. In earlier centuries this was a common general name for a hare as well as for a cat. He isn’t just talking about his own hare of that name.

‘Mr Urban, May 28

Convinced that you despise no communications that may gratify curiosity, amuse rationally, or add, though but a little, to the stock of public knowledge, I send you a circumstantial account of an animal, which, though its general properties are pretty well known, is for the most part such a stranger to man, that we are but little aware of its peculiarities. We know indeed that the hare is good to hunt and good to eat, but in all other respects poor Puss is a neglected subject.

In the year 1774, being much indisposed both in mind and body, incapable of diverting myself either with company or books, and yet in a condition that made some diversion necessary, I was glad of any thing that would engage my attention without fatiguing it. The children of a neighbour of mine had a leveret given them for a plaything; it was at that time about three months old.

Understanding better how to tease the poor creature than to feed it, and soon becoming weary of their charge, they readily consented that their father, who saw it pining and growing leaner every day, should offer it to my acceptance. I was willing enough to take the prisoner under my protection, perceiving that in the management of such an animal, and in the attempt to tame it, I should find just that sort of employment which my case required. It was soon known among the neighbours that I was pleased with the present; and the consequence was, that in a short time I had as many leverets offered to me as would have stocked a paddock. I undertook the care of three, which it is necessary that I should here distinguish by the names I gave them, Puss, Tiney, and Bess.

Notwithstanding the two feminine appellatives, I must inform you that they were all males. Immediately commencing carpenter, I built them houses to sleep in; each had a separate apartment so contrived that their ordure would pass thro’ the bottom of it; an earthen pan placed under each received whatsoever fell, which being duly emptied and washed, they were thus kept perfectly sweet and clean. In the daytime they had the range of a hall, and at night retired each to his own bed, never intruding into that of another.

Puss grew presently familiar, would leap into my lap, raise himself upon his hinder feet, and bite the hair from my temples. He would suffer me to take him up and to carry him about in my arms, and has more than once fallen asleep upon my knee. He was ill three days, during which time I nursed him, kept him apart from his fellows that they might not molest him (for, like many other wild animals, they persecute one of their own species that is sick), and, by constant care and trying him with a variety of herbs, restored him to perfect health. No creature could be more grateful than my patient after his recovery; a sentiment which he most significantly expressed, by licking my hand, first the back of it, then the palm, then every finger separately, then between all the fingers, as if anxious to leave no part of it unsaluted, a ceremony which he never performed but once again upon a similar occasion.

Finding him extremely tractable, I made it my custom to carry him always after breakfast into the garden, where he hid himself generally under the leaves of a cucumber vine, sleeping or chewing the cud till evening; in the leaves also of that vine he found a favourite repast. I had not long habituated him to this taste of liberty, before he began to be impatient for the return of the time when he might enjoy it. He would invite me to the garden by drumming upon my knee, and by a look of such expression as it was not possible to misinterpret. If this rhetoric did not immediately succeed, he would take the skirt of my coat between his teeth, and pull at it with all his force. Thus Puss might be said to be perfectly tamed, the shyness of his nature was done away, and on the whole it was visible, by many symptoms which I have not room to enumerate, that he was happier in human society than when shut up with his natural companions.

Not so Tiney. Upon him the kindest treatment had not the least effect. He too was sick, and in his sickness had an equal share of my attention; but if, after his recovery I took the liberty to stroke him, he would grunt, strike with his fore feet, spring forward and bite. He was, however, very entertaining in his way, even his surliness was matter of mirth, and in his play he preserved such an air of gravity, and performed his feats with such a solemnity of manner, that in him too I had an agreeable companion.

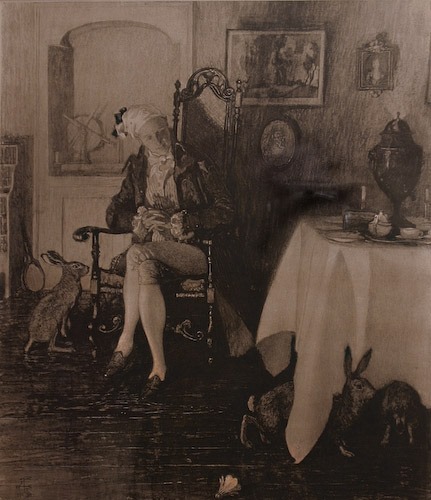

Bess, who died soon after he was full grown, and whose death was occasioned by his being turned into his box which had been washed, while it was yet damp, was a hare of great humour and drollery. Puss was tamed by gentle usage; Tiney was not to be tamed at all; and Bess had a courage and confidence that made him tame from the beginning. I always admitted them into the parlour after supper, when the carpet affording their feet a firm hold, they would frisk and bound and play a thousand gambols, in which, Bess, being remarkably strong and fearless, was always superior to the rest, and proved himself the Vestris of the party [Auguste Vestris (1760-1842), a celebrated French dancer]. One evening the cat being in the room had the hardiness to pat Bess upon the cheek, an indignity which he resented by drumming upon her back with such violence, that the cat was happy to escape from under his paws and hide herself.

You observe, Sir, that I describe these animals as having each a character of his own. Such they were in fact, and their countenances were so expressive of that character, that, when I looked only on the face of either, I immediately knew which it was. It is said, that a shepherd, however numerous his flock, soon becomes so familiar with their features, that he can by that indication only distinguish each from all the rest, and yet to a common observer the difference is hardly perceptible. I doubt not that the same discrimination in the cast of countenances would be discoverable in hares, and am persuaded that among a thousand of them no two could be found exactly similar; a circumstance little suspected by those who have not had opportunity to observe it: these creatures have a singular sagacity in discovering the minutest alteration that is made in the place to which they are accustomed, and instantly apply their nose to the examination of a new object.

A small hole being burnt in the carpet, it was mended with a patch, and that patch in a moment underwent the strictest scrutiny. They seem too to be very much directed by the smell in the choice of their favourites; to some persons, though they saw them daily, they could never be reconciled, and would even scream when they attempted to touch them; but a miller coming in, engaged their affections at once; his powdered coat had charms that were irresistible. You will not wonder, Sir, that my intimate acquaintance with these specimens of the kind has taught me to hold the sportsman’s amusement in abhorrence; he little knows what amiable creatures he persecutes, of what gratitude they are capable, how cheerful they are in their spirits, what enjoyment they have of life, and that, impressed as they seem with a peculiar dread of man, it is only because man gives them peculiar cause for it.

That I may not be tedious, I will just give you a short summary of those articles of diet that suit them best, and then retire to make room for some more important correspondent.

I take it to be a general opinion that they graze, but it is an erroneous one, at least grass is not their staple; they seem rather to use it medicinally, soon quitting it for leaves of almost any kind. Sowthistle, dent-de-lion [dandelion], and lettuce are their favourite vegetables, especially the last. I discovered by accident that fine white sand is in great estimation with them; I suppose as a digestive. It happened that I was cleaning a bird-cage while the hares were with me; I placed a pot filled with such sand upon the floor, to which being at once directed by a strong instinct, they devoured it voraciously; since that time I have generally taken care to see them well supplied with it. They account green corn a delicacy, both blade and stalk, but the ear they seldom eat; straw of any kind, especially wheat-straw, is another of their dainties; they will feed greedily upon oats, but if furnished with clean straw never want them; it serves them also for a bed, and, if shaken up daily, will keep sweet and dry for a considerable time. They do not indeed require aromatic herbs, but will eat a small quantity of them with great relish, and are particularly fond of the plant caned musk; they seem to resemble sheep in this, that, if their pasture be too succulent, they are very subject to the rot; to prevent which, I always made bread their principal nourishment, and, filling a pan with it cut into small squares, placed it every evening in their chambers, for they feed only at evening and in the night; during the winter, when vegetables are not to be got, I mingled this mess of bread with shreds of carrot, adding to it the rind of apples cut extremely thin; for tho’ they are fond of the paring, the apple itself disgusts them.

These, however, not being a sufficient substitute for the juice of summer herbs, they must at this time be supplied with water; but so placed, that they cannot overset it into their beds. I must not omit that occasionally they are much pleased with twigs of hawthorn and of the common briar, eating even the very wood when it is of considerable thickness.

Bess, I have said, died young; Tiney lived to be nine years old and died at last, I have reason to think of some hurt in his loins by a fall. Puss is still living, and has just completed his tenth year, discovering no signs of decay nor even of age, except that he is grown more discreet and less frolicksome than he was. I cannot conclude, Sir, without informing you that I have lately introduced a dog to his acquaintance, a spaniel that had never seen a hare to a hare that had never seen a spaniel. I did it with great caution, but there was no real need of it. Puss discovered no token-of fear, nor Marquis the least symptom of hostility. There is therefore, it should seem, no natural antipathy between dog and hare, but the pursuit of the one occasions the flight of the other, and the dog pursues because he is trained to it: they eat bread at the same time out of the same hand, and are in all respects sociable and friendly.

Yours, &c., W.C.

P.S. I should not do complete justice to my subject, did I not add, that they have no ill scent belonging to them, that they are indefatigably nice in keeping themselves clean, for which purpose nature has furnished them with a brush under each foot; and that they are never infested by any vermin.’

Cowper wrote the epitaph below in March 1783, following the death of Tiney. It anticipates many of the observations in the letter, more formally but still with great lightness of touch. Puss died on 9 March 1786, aged 11 years, 11 months.

Epitaph on a Hare

Here lies, whom hound did ne’er pursue,

Nor swifter greyhound follow,

Whose foot ne’er tainted morning dew,

Nor ear heard huntsman’s hallo,

Old Tiney, surliest of his kind,

Who, nursed with tender care,

And to domestic bounds confined,

Was still a wild Jack-hare.

Though duly from my hand he took

His pittance every night,

He did it with a jealous look,

And, when he could, would bite.

His diet was of wheaten bread,

And milk, and oats, and straw,

Thistles, or lettuces instead,

With sand to scour his maw.

On twigs of hawthorn he regaled,

On pippins’ russet peel,

And, when his juicy salads failed,

Sliced carrot pleased him well.

A Turkey carpet was his lawn,

On which he loved to bound,

To skip and gambol like a fawn,

And swing his rump around.

His frisking was at evening hours,

For then he lost his fear;

But most before approaching showers,

Or when a storm drew near.

Eight years and five round-rolling moons

He thus saw steal away,

Dozing out all his idle noons,

And every night at play.

I kept him for his humour’s sake,

For he would oft beguile

My heart of thoughts that made it ache,

And force me to a smile.

But now, beneath this walnut-shade

He finds his long, last home,

And waits, in snug concealment laid,

Till gentler Puss shall come.

He, still more aged, feels the shocks,

From which no care can save,

And, partner once of Tiney’s box,

Must soon partake his grave.