Cowper is renowned for his letters. Here we look at his ‘filing cabinet’, the paper, pens and ink he used, and the postal system he depended upon.

A personalised letter cabinet

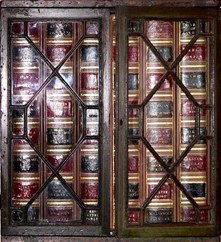

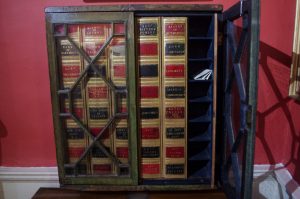

Our cabinet operates as a filing system for Cowper’s correspondence. It hangs on the wall of his one-time parlour, over his knee-hole writing desk, but could equally well serve as a standing cabinet set upon a table or other such surface. It measures roughly two and a half feet (72 cm.) in height and two feet (61 cm) wide and is attractively glazed and barred.

‘The look’ is suggestive of the top half of a miniature secretaire designed to hold books. And this idea is further played out behind the glass doors, where there appear to be lodged six giant leather-bound volumes, each exactly the height of the cabinet, and each bearing eight title-pieces. The ‘spines’ are neatly labelled with gold lettering on alternate black and red leather panels, running down the full length of each ‘volume’. There is further gold work decoration stamped between each label, adding to the magnificent appearance of these leather ‘bindings’. Look a little closer at the lettering however, and we see that the labels are not, as one might expect, the titles of books, or names of authors and publishers, rather they are the names of people with whom Cowper corresponded.

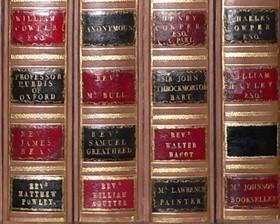

All but eight of the forty-eight title-pieces bear a name. Across the top row, there is a series of men of the cloth, starting with the Bishop of London. The second row of labels gives the names of members of the nobility, including the poet’s most prestigious relative, Earl Cowper. The third row is reserved to women correspondents: Indications like ‘Judge Rowley of Ireland’ and ‘American correspondent’ offer evidence of the geographical reach of Cowper’s contacts, and ‘Anonymous’, a reminder that letters were often unsigned. Some labels give further details, like ‘Professor Purdis of Oxford University’ or ‘William Wilberforce Esq. M.P.’

Included are the names of other relations such as Cowper’s cousin Lady Hesketh, and local dignitaries like the Throckmortons (Cowper in his letters refers to them affectionately as ‘Sir John and Lady Frog’) and the Earl of Dartmouth. William Hayley, poet and patron, is there too, and Henry Fuseli, the famous Swiss artist – these all hugger-mugger along with Mr. Pratt, ‘Engraver’, and Mr. Bacon, ‘Statuary’’. It’s a bit like playing ‘Happy Families’.

If we draw a little closer still and open the glass doors of the cabinet, we find that none of the six volumes can be pulled out. For these are not books at all, but a disguised filing system for Cowper’s post. So, behind each of the six hinged ‘spines’ there is a column of pigeonholes – small wooden compartments for letters to and from the correspondents named on the front.

It’s a delightful object and clearly designed especially for Cowper. It is said to have been commissioned for him in about 1796 by his young cousin the Revd John Johnson (‘Johnny of Norfolk’), with whom he lived in his declining years. As is well known, the two got on famously, and this cabinet is a lovingly thought-out gift. It also reminds us that letter-writing was a favourite diversion of Cowper’s as well as one of his greatest talents.

[Note: The letter cabinet was restored in 1985.Some of the labels are blank, as they may well always have been. More surprisingly, the name of the Revd Matthew Powley, vicar of Dewsbury in Yorkshire, and husband of Susannah Unwin, appears twice, once on the top, once on the bottom row, suggesting there may have been some confusion when the restoration work was carried out.]

Paper and postage

For his letters and other manuscripts Cowper needed various items of stationery. We’ll start with paper. In the eighteenth century this could be of variable quality. Indeed, in the occasional letter Cowper complained to his correspondent that he was working with a bad batch – sheets that were rough, slightly lumpy and caught the nib of his pen.

At this time, paper was made of pulverised rags. To make a sheet, a wired frame, the size of the paper to be, was dipped into a messy concoction of smashed up linen rags floating in a vat of water. The frame was lifted out carefully so as to pick up a layer of fibre laid on the wires and the water drained off. The resultant film of fibrous stuff was removed by turning the frame over and pressing it gently onto a cloth or ‘felt’. A stack of these (usually a quire) was built up, and the pile squeezed to remove more moisture. The sheets would then be separated, pressed and hung out to air dry. Finally, they would be sized (glued) to make them fit to write on without absorbing too much ink. But the process was not ideal: fibres vary in length and strength and drainage wires leave indentations, so these ‘laid’ writing papers were not always as smooth as they might be. Hence Cowper’s occasional complaints.

Despite being of variable and sometimes dubious quality, paper was expensive – it was taxed – and Cowper was always delighted to receive gifts of it. He writes to his cousin, Lady Harriot Hesketh:

‘Saturday, my dearest cousin, was a day of receipts. In the morning I received a box filled with an abundant variety of stationery ware, containing, in particular, a quantity of paper sufficient, well covered with good writing to immortalize any man. I have nothing to do therefore but to cover it as aforesaid, and my name will never die.’

His pleasure is not surprising, given that he used so much paper – not just for the extraordinary number of letters he wrote (usually before breakfast each day) but also for the handwritten texts of his books. Such gifts helped Cowper with his expenses and solved the problem of finding a good local source. Periodically he would ask his close friend Joseph Hill to send him supplies from London. (Hill knew Cowper from their law days together, and he more or less managed Cowper’s finances for him.) This is the kind of detailed request Hill would receive:

‘Will you be so good as to order for me half a ream of the best post paper? The stationer will be paid by the bookkeeper at the Windmill St John’s Street.’

Paper comes in named sizes but it can be hard to track what is being ordered or used as these names and their dimensions vary over time and place. Cowper talked of ‘royal’ paper (25 in. x 20 in.) as well as ‘post’ paper (19 in. x 15.5 in.) depending on the job he wanted the paper for; and he bought it by the ‘quire’ (24 sheets) or the ‘ream’ (480 sheets).

These measurements become a little more interesting perhaps, when we learn (from his letters) of the little rituals Cowper went through as he prepared his sheets of paper. For his practice varied according to whether he was writing a letter or a manuscript for a book.

If it were a manuscript, we learn that he folded the sheets in half and stacked them ‘book-wise’ within each other before he started to write:

‘I would gladly gratify you by sending the part of the translation which you desire…but there is an insuperable difficulty…the quire being written book fashion, the same sheet contains as much of what you do not want as of what you do. For instance if I send you page 1, I must also send you pages 41 and 42 which are found on the corresponding side of the same sheet.’

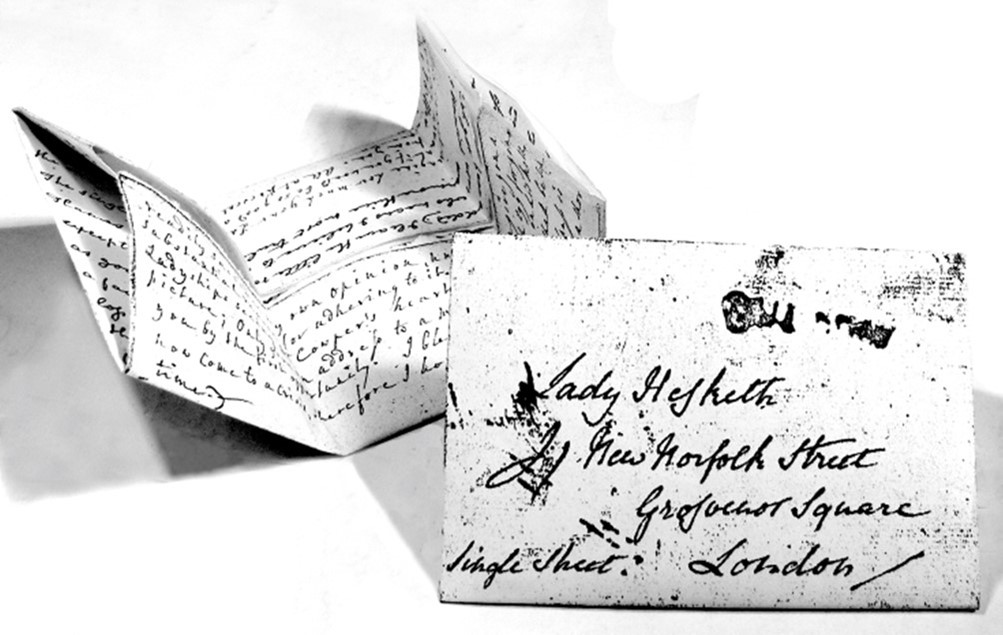

And when it came to letter writing, as we can see from this copy of a letter to his cousin Lady Hesketh, the same sheet of paper served to hold both message and address, so Cowper needed to fold a single sheet in such a way that it left space for an address on the front. Here he is describing how he would usually write round the edges of a page of paper, so as to leave space for the address:

‘See what habit has done, it has made me skip over the middle of the page without occasion… but I have two or three things in reserve that will fill it sufficiently.’

The reference just made to ‘a single sheet’ is not a casual one; if a correspondent used two sheets of paper rather than one, the postal charge doubled. (Postal costs were calculated by reference to the number of sheets used and the distance to be travelled.) Cowper was ever keen to keep the cost of postage down – even though this charge was collected from recipients rather than paid for by senders. We can read ‘single sheet’ on the illustrated letter front, but here is Cowper himself referring to this very point:

‘I perceive that this time I shall make you pay doubled postage…unless I write myself out now.’

Once folded, the single sheet, or the outer enclosing sheet, was secured with a drop of wax, often impressed with a seal while still soft, using a seal ring or fob. A trace of the wax mark is just visible in our illustration above. Cowper had a fine gold seal fob which, we are told, he always carried with him, so much was letter-writing a part of his everyday routine.

The postal system

The postal system of Cowper’s day – its costs and routes – is fascinating. And because he is such an avid letter-writer and often comments on such humdrum things, we pick up quite a deal of information about it from his correspondence. He mentions ‘franks’ for example. These were marks owned by individuals which, when stamped on a letter cover, allowed it free passage. Cowper was keen to come by these, as we see from a note to William Unwin:

‘Your mother sends her love and begs that when you write next you will send another frank, and then she will write too.’

Members of both Houses of Parliament – and a few other men of position – had the right to ‘frank’ their post and thus receive a number of free letters. It was a system apparently much abused, with friends begging into it and using this MP’s privilege in unwarranted ways. As Cowper’s request demonstrates, franked letters might be requested and then apparently sent on for someone else to use.

One particularly notorious abuser was the MP for Nottingham, a Mr Robert Smith, whom Cowper knew. Smith was said to be a very kind man who enjoyed sharing his franks around. On one occasion, for example, Cowper tells William Unwin that he’s just received from Smith

‘Not only franks to Johnson, but under another cover six to you…these…he threw in of his own mere bounty.’

Smith had provided Cowper with franks so that he might send manuscript proofs free to Johnson, his printer. Cowper was well aware of his obligation to the MP:

‘Your kindness to me…when you were so obliging as to frank the many pacquets that passed between me and my printer will expose you to future trouble. It is possible indeed that Johnson…may already have solicited you for that purpose. I will not wrong your readiness to assist me, by a formal apology, but will content myself with thanking you for a favour which I account already received’

‘Hark! ‘tis the twanging horn! O’er yonder bridge

That with its wearisome but needful length

Bestrides the wintry flood…

He comes, the herald of a noisy world,

With spattered boots, strapped waist, and frozen locks…

True to his charge, the close-packed load behind,

Yet careless what he brings, his one concern

Is to conduct it to the destined inn…’

From Cowper’s poem, ‘The Task’, opening lines of Book IV: The Winter Evening

As to the postal routes, these were very complicated and based on an old Tudor system of ‘posts’ or stages, each about twenty miles long. On this system a letter was passed from post to post, relay fashion. (The word ‘post’ comes to us from the Roman messaging service, whereby relays of messengers were stationed at their ‘posts’ or positions to receive and pass on messages.) Originally only six posts radiated from London, and although the number greatly expanded in the eighteenth century, much of the country was poorly served, and letters were still carried by post boys, with the dangers and unreliability this entailed. (Guarded mail-coaches only took over in 1784.) Indeed, rather than risk the rough, slow roads, with their highwaymen and robbers, it was sometimes thought better to use a waterway. But this wasn’t necessarily much safer; we know for example, that Cowper lost a manuscript (part of his translation of Homer) in the River Thames in a storm. He refers to this event in one of his letters:

‘I rejoice my dearest coz that my MSS have roam’d the earth so successfully and have met with no disaster. The single book excepted that went to the bottom of the Thames and rose again, they have been fortunate without exception.’

In a letter to his printer Cowper’s response to this event was typically phlegmatic, suggesting such carriage problems were par for the course. He merely commented ruefully,

‘My kind and generous cousin…is my transcriber also. She wrote the copy and she will have to write it again.’

But if using the road system, mail would be carried from post to post and delivered at each stage to a post master or mistress. In the early days of the general post, these were usually innkeepers as they kept the necessary horses and stabling; but later this was thought a little insecure and other local businesses – druggists, stationers, grocers – ran post offices. The officer in charge would take in the local letters and then arrange for them to be picked up or delivered. In Olney, Cowper tells us, the post was pretty regular:

‘Once more our post goes every day. A poor man for the sum of a shilling per day undertakes to walk 90 miles per week. A London porter would disdain such wages for such labour…’

The Lodge, Dec.14, 1786

To Lady Hesketh ‘my dearest coz’

‘… In the next place, if I know when to expect a letter, I know likewise when to enquire after a letter, if it happens not to come; a circumstance of some importance, considering how excessively careless they are at the Swan, where letters are sometimes overlooked, and they do not arrive at their destination, if no inquiry be made, till some days have passed after their arrival in Olney.’

In some parts of the country there was no easy access to this system of post roads and it took a mid-century development – the introduction of ‘cross-roads’ and ‘by posts’ – to make the service more attractive and economically viable. A ‘cross-road’ ran between two post roads, while a ‘by-post’ ran between a post road and a town somewhat at a distance from it. Meanwhile, and very helpfully, a ‘way-letter’ was one that might be carried between two towns on the same post road.

Cowper’s letters bring a little local colour to this complicated-sounding system. For instance, he tells us that in 1791,

‘We have met some rubs lately in the affair of the by-post…and…all the danger that seemed to threaten us was occasioned by the post-mistress at Olney.’

Apparently there had been trouble with mail carried on the by-post running from Weston Underwood to Olney. Cowper had asked a London friend to complain about this for him to the General Post Office. The complaint must have been looked into, for the unfortunate post-mistress was held responsible and removed from office.

Pens, pencils and ink

Cowper also needed tools, such and pens and ink, to produce all these letters and scripts. We see from this close up of Cowper’s hand from his portrait by Lemuel Abbott (1792) that he used a quill pen to write with.

Quill pens were widely used and had been around from the fifth century. (The word pen comes from ‘penna’, Latin for feather.)

Whilst quills were often made from goose-feathers, wing feathers from turkeys, swans, peacocks and crows were also popular. Cowper doesn’t specify what type he preferred. Quills made supple, flexible writing tools but they needed to be carefully cut and tended to needed re-cutting quite often (with a special pen-knife) when they lost their point. Apparently, it took considerable skill to cut a good nib and consequently some pens worked much better than others. An exasperated Cowper writes:

‘Having begun my letter with a miserable pen, I was not willing to change it for a better lest my writing should not be all of a piece, but it has worn me and my patience quite out.’

It is interesting to see that he apparently minded about the overall ‘look’ of his letter as well as its content.

As to pencils, he tells us of one that particularly took his fancy. This was another present from Harriot, one that arrived by second delivery on that ‘day of receipts’ looked at earlier. Cowper said of this parcel:

‘In the evening I received a smaller box…It contained an almanac in red morocco, a pencil of a new invention, called an everlasting pencil, and a noble purse, with a noble gift in it, called a bank note for twenty-five pounds.’

The pencil was probably an early kind of propelling pencil – a thin rod of lead encased in bone or metal, to protect the graphite from breaking and the writer’s fingers from getting blackened.

Turning to the ink Cowper used, no definitive evidence has surfaced yet. But there were many rather crude recipes for home-made ink around – most from the sixteenth century – and it seems likely that Cowper used one for ‘carbon black’ (or ‘lampblack’) ink, which was widely used in Europe by the seventeenth century.

Lampblack ink was made by collecting soot from lamp wells and mixing this into a paste with a binder such as gum-arabic, and diluting it with water. This ink might be dried into cakes or sold as sticks, much like the Chinese calligraphy ink sticks available today.

For a time, Cowper found drawing a happier diversion than writing, taking lessons in 1780 from local artist James Andrews. We know that he asked William Unwin to buy what he called ‘Indian ink’ for this purpose, amongst other items on his shopping list.

‘I add…Indian ink, a few brushes and a pencil or two, with anything else that might be convenient for the use of a beginner, as far as five shillings…I don’t think my talent in the art worth more.…My scribbling humour has of late been entirely absorbed in the passion of landscape drawing. It is a most amusing art and like every other art requires much practice and attention.’

However, by ‘Indian ink’ he probably meant the usual lampblack ink just mentioned. This was popular as it had a good strong colour and did not fade quickly, its main drawback being that it could be rather sticky and clog a writer’s nib. Cowper does mention such a ‘gluey’ effect on occasion. But generally ink was not hard to come by: chemists made and sold it in bottles, and in larger towns it was available from street vendors.

Some conclusions

There is perhaps no better way to end than by quoting a few of Cowper’s own conclusions to his letters. For he often signs off entertainingly, combining eloquent flourishes with remarkable requests. Here’s an example to Johnny Johnson, the man behind our letter cabinet:

‘It is ten o’clock and I must breakfast – Adieu therefore my Dear Johnny – remember your appointment to see us in October…yours ever, Wm Cowper.’

‘Remember too a ream of paper of this size, and by no means omit to order us directly some White Brandy.’

To Lady Hesketh, (occasionally addressed as his ‘Dearest Cozywozzy’), he closed one letter with a typical ‘thank you’ for some previous gift, and a P.S.

‘Thanks for an incomparable cheese.

With Mrs. U’s affectionate remembrances I am most truly thine

Wm. Cowper.

P.S.

Don’t forget to send me some bits of wax-candle.’

While in another P.S. to Harriot (did recipients find these rather ominous?) he writes:

‘Adieu my dearest Coz – with the love of all here

I remain ever thine Wm. Cowper

P.S.

We packed the drawings as well as we could, but the band-box was old and crazy and was crushed I suppose in the hamper. I sent them that you might get them framed at your best leisure, for here we cannot frame them.’

But here, and to end with, is a gentler envoi to his beloved cousin:

‘The clock strikes 9. Good night, my dear, and God Bless thee –

Yours ever Wm. Cowper’

Further Reading

King, James, and Ryskamp, Charles (eds.), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 5 vols, 1979-86). All quotations from Cowper’s letters are taken from this edition.

Professor Catriona Seth, ‘Cowper’s Letter Cabinet‘. An article from ‘Romantic Dwellings’ on the website of ‘European Romanticisms in Association’

Elizabeth Knight, The Old Inns of Olney, Barracuda Books 1981

Vincent Newey, ‘The Loop-holes of Retreat: Exploring Cowper’s Letters’ The Cowper & Newton Journal