Our examination of this small bottle prompts reflections on perfumes, herbal remedies, gardening and the English weather. It was given to Wordsworth after Cowper’s death.

The Wordsworth connection

William Wordsworth (1770-1850) admired Cowper’s work, and was influenced by it. In a letter of 22 December 1814, he wrote:

‘…with the exception of Burns and Cowper, there is very little of recent verse, however much it interests me, that sticks in my memory (I mean what I get by heart).’

In many ways Cowper prefigured Romanticism, writing directly and freshly about Nature and the inner life of the individual. Indeed, it may be argued that The Task directly influenced the form and content of Wordsworth’s great autobiographical poem The Prelude

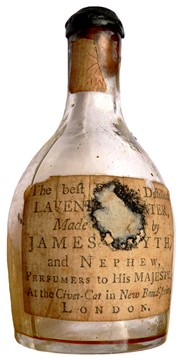

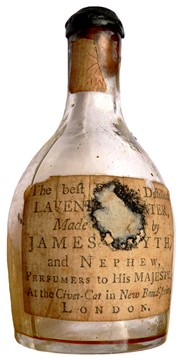

There is a note in the museum collection saying that Cowper had used the lavender water in this bottle not long before he died in 1800. It was later given to Wordsworth as a memento of Cowper, at that time regarded as the foremost poet of the day. We do not know if Wordsworth or a member of his family requested it, or whether it was given to him as a gesture by Cowper’s heirs. Whatever the means by which it came into Wordsworth’s possession, the bottle eventually found its way back to Olney as a gift from Dorothy Dickson, Wordsworth’s great-granddaughter. Our tiny flask, in its journey from London to Olney, to the Lake District, and back to Olney, has gathered powerful literary associations and become a token of one great poet’s regard for another.

A Bond Street perfumer

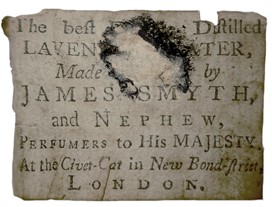

Our bottle once contained a distillation of lavender. It was purchased for Cowper from the London shop of James Smyth and Nephews, perfumers to George II and George III.

An early record of Smyth’s business (in the Daily Advertiser of 1743) shows that he occupied a shop ‘at the Civet-Cat’ in New Bond Street (civet is a perfume made from the glandular oils secreted by a civet cat.) A billhead of 1757 records the sale, to the Duke of Bedford’s household, of a bottle of distilled lavender water for 5 shillings and 2 pence (worth approximately £30 in today’s currency). Household accounts reveal that Smyth and Nephew went on supplying the Bedfords with their ‘Best Distilled Lavender Water’ until the late 1760s.

The bottle is itself a delight. It is 11 cm. high and similar, in miniature form, to a late Georgian, plain glass decanter. It has a small pontil mark on its base, formed when the glass blower’s rod (the pontil) was broken off; and a cork stopper which was held in place with a black wax seal.

James Smyth’s paper label is elegantly shaped to hug the lower, swollen-bellied, two thirds of his bottle. It is printed in italic and roman type, in a font invented by William Caslon in 1722. Caslon is the most common font used in eighteenth-century printing in England and America. Note the distinctive long ‘s’ of the period in the middle of some words, and the way the designer has sized the lettering carefully so that it fits and enhances the narrowing at the bottle’s base.

Lavender and its uses

Lavender has been used as a cosmetic, an unguent and a medicine for centuries. Wealthy, high status Egyptians used it both as a perfume (aromatic traces were detected in urns found in the tomb of King Tutankhamen) and in the embalming process. Both Greeks and Romans used lavender for the healing qualities associated with its scent. According to the Greek philosopher Diogenes, it was important to apply lavender oil to the feet rather than to the head (as the Egyptians did) so that its perfume didn’t just fly up and ‘benefit the birds’, but worked its way gradually up the body and ‘gratefully ascended’ to the nose.

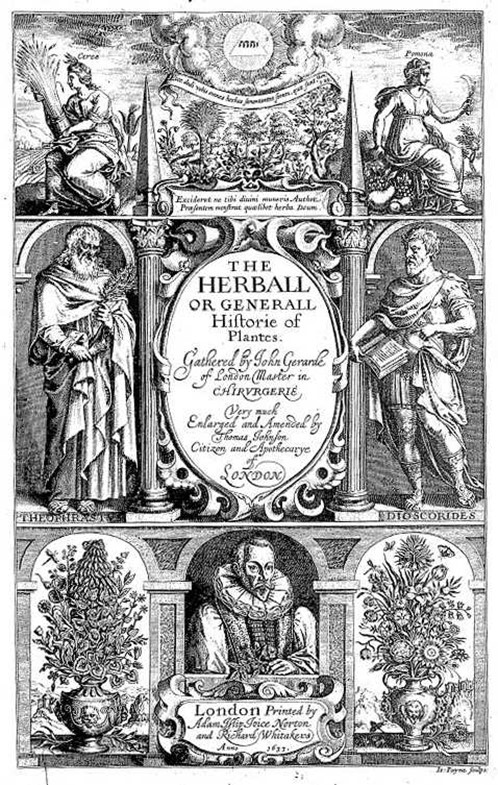

The first surviving written record of its medical benefits appears in a five-volume work by Dioscorides, the Roman emperor Nero’s Greek physician. Dioscorides claimed that lavender, when ingested, would relieve indigestion, headaches and sore throats; when applied externally it would help to clean wounds, soothe burns and treat other skin ailments.

Pliny the Elder (a renowned Greek traveller and encyclopaedia writer) noted even more medical applications in his studies of foreign customs. He recorded the frequent use of lavender for internal ailments such as stomach upsets, kidney diseases, jaundice and dropsy. He also reported that women used it to address menstrual problems or might hang it near their beds to ‘incite the passions’.

Moving through the centuries to the middle ages and over to England, we find many a monastery garden with lavender amongst its medicinal plants. At this time most medicine was herbally based. Plants such as tansy, rue and mint, in particular, contained ingredients that became associated with various medicaments. Many such therapies survive to this day, carried on through tradition and herbal lore as well as with the support of plant sciences.

The dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII ended many of their privileged garden practices. Lavender growing became more domesticated and more widespread. As is perhaps well-known, it was much used in sixteenth-century Tudor England as a sweetener of the air: on floors as a strew herb, as pot-pourri around rooms, or sewn into bags for personal use. Its scent was much exploited in laundry work as an insect repellent as well as a disinfectant and fabric freshener. Indeed, the word ‘lavender’ probably comes from the Latin ‘lavare’, to wash, and has been used in bathing from Roman times to today.

Following the invention of printing, the sixteenth century also saw the growth of instruction manuals and practical books on how to make and do almost everything. Amongst such manuals we find herbals advocating the use of lavender and other plants. One of the first was written by Antony Ascham in 1525, followed in 1597 by the famous Herball, or Generall Historie of Plantes by John Gerard.

Both of these Elizabethan writers recommended the growing and use of lavender, and for (by now) fairly traditional reasons. It was the scent which Ascham believed made lavender an excellent soak (for weary ankles) or a good bandage for wrapping round aching temples to induce sleep. Gerard contributed the idea that lavender had cosmetic benefits: that it would reduce freckles as well as help with skin complaints such as spots or rashes.

By the seventeenth century lavender had become very popular and could be bought fairly easily from street sellers. At this time it was recommended as protection against almost every infection – from cholera and the plague (the Great Plague of 1665 in particular) to the relief of the common cold, with its rheumy headaches, cuts and wounds and general discomforts.

Cowper’s garden

And so to Cowper and his gardens. When he moved to Orchard Side, Olney, in 1768, he took over the tree, shrub and flower area near the house. He was an avid gardener enjoying all aspects of the work, growing from seed, propagating and nurturing all sorts of plants – vegetables as well as flowering species. Many of these were rare at the time. In his letters Cowper delights in boasting of the exotics he has caused to flourish, especially when he manages to do so before the owners of neighbouring large estates. He is quite competitive in this respect and very proud of his self-built greenhouse – ‘my favourite recess’ and ‘summer parlour’ – that helps him achieve such good results.

He also writes eloquently of the perfumes rising from his flowers: myrtles, roses, carnations, mignonettes, honeysuckles, jasmines and balsams. A full list of these would be very long indeed. As he writes in a letter to John Newton of 1784, he is

‘… regaled with the scent of every flower in a garden as full of flowers as I have known how to make it’

He must have grown lavender too, although this is not mentioned as a favourite. And he would certainly have welcomed the refreshing smell as he brushed by it, for Olney was hardly a scented paradise at that time. In another letter, written in a hot August, he mentions that he spends most of his time in the greenhouse,

‘…as it affords us by far the pleasantest retreat in Olney…not to mention the exchange of a sweet smelling garden for the putrid exhalations of Silver End’

Silver End – just round the corner from the Market Place, and Orchard Side – was the poorest part of Olney and inhabited largely by the hard-pressed lacemakers of the town.

Beyond Cowper’s flower garden was an area originally belonging to, and planted up by a local physician. Dr Aspray. His garden would have contained a range of medicinal plants used in his Olney trade – both herbs and woodier spices. He would have grown a range of key herbs known from medieval days, such as savory, sage, rue, rosemary, peppermint, bergamot, lovage and fennel as well as thyme, horehound, sorrel, lovage, feverfew, lavender, comfrey and tansy (and more besides!). Amongst the spices grown, we could expect to have seen cumin, anise, dill and fenugreek.

In the eighteenth century such plants were prepared in many ways (as teas, poultices or just cleaned) and used for all kinds of ailments, inside and out. All parts of a plant – flowers, leaves, roots, stems, bark or seeds – might be used. The softer, such as leaves and flowers would generally be infused – that is, soaked in hot water for about a quarter of an hour as in tea-making – while the tougher bits (like stems, roots and bark) would be boiled down for longer to make what is called a decoction.

Our lavender bottle contained a distillation – a condensed form of infusion. To make this, the flowers would have been infused in water, then brought to the boil and the steam captured. It is a process distinct from ‘tincture’ making, where a herb is infused in alcohol so as to absorb its soluble parts.

Of meteorites and plague – a time for lavender

In his letters Cowper enjoyed describing remedies for treating various maladies and indispositions. He had a strong interest in the latest medical ideas as well as in well-worn ways of relieving physical problems. His own included headaches, digestive disorders, sleeplessness and eye complaints. For Mrs Unwin, his companion, there was the aftermath of a stroke to cope with, and for others, appropriate treatments for smallpox, consumption, constipation, knock knees and squints.

The year 1783 was marked by an exceptional prevalence of ill health in Olney. There were four miserable months in particular, when non-pernicious refreshers and curatives such as lavender water must have felt like a necessity, not just a bonus. It all began in the summer of that year. On 13 June Cowper wrote to John Newton describing dire weather and alarming events taking place in the atmosphere:

‘The fogs I mentioned in my last still continue, though till yesterday the Earth was as dry as intense heat could make it. The sun continues to rise and set without his rays, and hardly shines at noon, even in a cloudless sky. At eleven last night the moon was of a dull red; she was nearly at her highest elevation, and had the colour of heated brick…We have had more thunderstorms than have consisted well with the peace of the fearful maidens of Olney, though not so many as have happened in places at no great distance, nor so violent. Yesterday morning, however, at 7 o’clock, two fire-balls burst either in the steeple or close to it. William Andrews saw them meet at that point, and immediately after saw such a smoke issue from the apertures in the steeple as soon rendered it invisible…when Joe Green went afterward to wind the clock, flakes of stone and lumps of mortar fell about his ears in such abundance, that he desisted, and fled terrified. The noise of that explosion surpassed all the noises I ever heard; – you would have thought that a thousand sledge-hammers were battering great stones to powder, all in the same instant. The weather is still as hot, and the air as full of vapour, as if there had been neither rain nor thunder all the summer.’

And on 29 June he continues:

‘So long, in a country not subject to fogs, we have been covered with one of the thickest I remember. We never see the sun but shorn of its beams, the trees are scarce discernable at a mile’s distance, he sets with the face of a red hot salamander and rises with the same complexion…some fear to go to bed, expecting an earthquake…some assert that the day of judgment is at hand.’

In August, Cowper tells the Reverend William Bull, of Newport Pagnell, about ongoing storms:

‘I was always an admirer of thunderstorms…We have indeed been regaled with some of these bursts of ethereal music. – The peals have been as loud, by the report of a gentleman who lived many years in the West Indies, as were ever heard in those islands, and the flashes as splendid.’

And on 3 September Cowper is still reflecting on the bad weather of that summer and on the resulting illnesses:

‘…having been myself seized with a fever immediately after your departure…The reveries your head was filled with while your disorder was most prevalent, though they were but reveries and the offspring of an heated imagination…I had none such. It would have been wonderful if I had. Indeed I was in no degree delirious, nor has anything less than a fever really dangerous ever made me so. In this respect if in no other I may be said to have a strong head … an ordinary degree of fever has no effect upon my understanding. The epidemic begins to be more mortal as the autumn comes on. Two men of drunken memory have died of it since you went, and in Bedfordshire it is reported, how truly I cannot say, to be nearly as fatal as a plague.’

On 23 September, Cowper, writing again to John Newton, still sounds poorly, but it is the number of townsfolk dying around him that is striking:

‘For my own part, though I have not been laid up, I have never been perfectly well since you left us. A smart fever…succeeded by a lassitude and want of spirits that seemed to indicate a feverish habit, has made me unfit??? for writing and reading; so that even a letter, and even a letter to you, is not without his burthen. An emetic which I took yesterday has I believe done me more good than any thing…John Line has had the epidemic and has it still…Bett Fisher was buried last night – she died of the distemper, Molly Clifton is dying, but of a decline…poor John has been very ready to depart…Oh what things pass in cottages and hovels which the Great never dream of.’

It has clearly been an appalling time, four months of oppressive air, darkness, humidity and sickness. At the end of September, Cowper writes to William Unwin (Mrs Unwin’s son) looking back over the summer:

‘You are happy in having hitherto escaped the epidemic fever, which has prevailed much in this part of the Kingdom, and carried many off. Your Mother and I are well. After more than a fortnight’s indisposition … I am at length restored by a grain or two of Emetic Tartar. It is a tax I generally pay in Autumn. By this time, I hope, a purer ether than we have seen for months, and these brighter suns than the summer had to boast, have cheered your spirits… The cattle in the fields show evident symptoms of lassitude and disgust in an unpleasant season; and we, their lords and masters, are constrained to sympathise with them.’

A time indeed for the soothing scent of lavender water.

Further Reading

James Smyth & Nephews Bill-head in Heal Collection, British Museum

The herball or, generall historie of plantes / Gathered by John Gerarde … Very much enlarged and amended by Thomas Johnson. Gerard, John, 1545-1612, 1633