William Cowper and John Newton are the most famous residents of Olney, but William Legge, the 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, is probably the most significant non-resident figure in Olney history..

In 1755 he married Frances Nicholls daughter to Charles Gunter (or Gounter) Nicholls, who had been MP for Peterborough. The family fortunes had been founded on the actions of Colonel George Gunter, who planned and helped Charles II escape, by boat, from Shoreham after the battle of Worcester.

Frances was one of the wealthiest heiresses in the country, with a marriage settlement including the manors of Olney, Warrington and Bradwell Abbey.

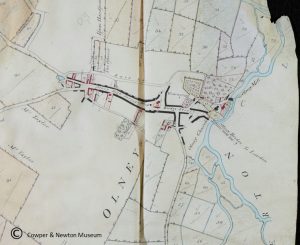

The museum exhibits the Dartmouth Survey of these estates from 1796, in the Georgian Life Room, which contains the earliest known detailed map of Olney.

‘The Earl of Dartmouth is Lord of the Manor of Olney, which comprises the Lordship at Hamlet of Warrington, and also Impropriator and Owner of all the Tithes both great and small, within Olney and Warrington; – his Lordship presents to the Vicarage of Olney, and pays a stipend of £70 per annum to the Vicar, who has no glebe, land or tithes.’

William Legge was from a prominent family. His grandfather was a naval commander and created Baron Dartmouth, and his father was Secretary of State for the Southern Department, effectively Foreign Secretary. William held a similar position as Secretary of State for the Colonial Department during an important period (1772-1775) at the outbreak of the American War of Independence. He held a number of other public positions over his lifetime and George III was said to be personally very fond of him.

He was educated at Westminster School and took an MA at Trinity Oxford and went on the customary Grand Tour with his half-brother Frederick North, later Lord North, Prime Minister at the time of the loss of the American colonies.

The Earl had a substantial country seat at Sandwell Hall in the Midlands, demolished in 1828. He also had a London townhouse at Blackheath (a subsidiary title is Viscount Lewisham).

With all his other properties, he had no need of the Olney Great House, standing behind the churchyard by the river.

Rev John Newton was therefore able to have the use of it for his Sunday schools and prayer meetings. Both Cowper and Newton wrote hymns for the occasion when in 1769 the Tuesday payer meeting for adults was moving into the largest room in the Great House. Jesus, whe’re’er thy people meet’ written by Cowper and ‘On Opening a Place for Social Prayer’ by Newton.

He dramatically changed the appearance of Olney when he enclosed (inclosed) the medieval open fields in 1767 by Act of Parliament, one of the first passed for this purpose in the county. He was personally allotted 1300 acres or about 70% of the total. Enclosure is believed to have tripled a landlord’s rental income in Olney, made farming more generally efficient and more profitable, but had the effect of forcing many poor peasants, with undocumented customary rights, from the land. They fell to the mercy of the Poor Law and Poor Houses or moved to the towns and cities to work in the factories of the emergent Industrial Revolution.

Enclosures dramatically changed the look of the countryside with smaller more regular fields, often more pastureland, new hedgerows, drainage and roads. Although William Cowper thought that “God made the country, and man the town”, he must have been aware of the developments occurring around him in the late 1760s and 1770s but never commented about them. But then he was a man of similar background to the Earl, important to his friend John Newton, and he even sat next to the Earl in the 6th form of Westminster School. It was left to Oliver Goldsmith to voice “Ill fares the land”, criticising these dramatic changes in the countryside, in his poem The Deserted Village of 1770.

He was also famous as a philanthropist, funding institutions such as the the Lock Hospital for ‘fallen women’ in London and as Vice-President of the Foundling Hospital in London.

The American manuscripts of the Earl of Dartmouth are considered to be one of the most important private

sources in Britain for the history of the American Revolution. From 1772 to 1775 he was Secretary of State for the American Colonies and had spoken against the Stamp Act.

The first black African American poet, Phillis Wheatley had met him in London and wrote a hopeful poem to him. The prestigious Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, USA was also named after him.

As an evangelical Christian on the Methodist wing of the Anglican Church, Dartmouth was also associated with Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon. She was a central figure in the evangelical revival in 18th-century England, and founded the Countess of Huntingdon’s Connexion, a sect of Calvinistic Methodists.

Lord Dartmouth owned the right to appoint a vicar and curate at the church in Olney. When he heard of John Newton’s years of struggle to enter the Church, and read his dramatic autobiographical letters, he arranged for him to be appointed Curate-in-Charge. The Vicar, Moses Brown, had moved to the chapel of Morden College near the Earl’s London home, retaining his Olney income to help support his thirteen children, a common practice in those days.

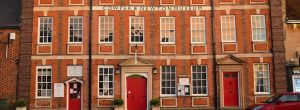

The family’s land and buildings were sold off after the First World War and the Market Place was purchased by the Town Council in 1941. There is still a Dartmouth House on Dartmouth Road at the north end of Olney.

Today there is a 10th Earl, also named William Legge, until recently a UKIP MEP, whose mother was Raine Spencer, making him a stepbrother of Princess Diana, and his Grandmother was romantic novelist Dame Barbara Cartland.