Here we look at a decorative item dating from the early 1700s. A few years ago, two sheets of wallpaper were brought into the museum, from a house on the Market Place, only a few doors away. They are a marvellous and rare find – paper hangings such as these are fragile and do not often survive the wear and tear of daily use, much less any destructive shifts in fashionable taste. Our papers are decorated with Chinoiserie motifs, and later in this article we will look at the taste for ‘things Eastern’ in the eighteenth century, as well as at paper making and at what is known about early paper wall coverings.

Please note these items are not on permanent display in the museum.

Dating the Paper

But first, why are we so confident that this paper dates from the beginning of the eighteenth century?

Firstly, because of the helpful excise stamp we can see on the reverse of each sheet.

This elaborate tax mark places the paper in the reign of George I (1714-1727). Paper had been taxed in England since 1694, but in 1712 an additional tax was brought in, largely to pay for the expensive wars then being waged in Europe, which continued for much of the eighteenth century. In 1712 paper that was to be painted, printed or stained for a wall hanging was taxed at one penny a square yard, and by the 1780s it was nearly double this. Since paper-stainers were already obliged to pay an annual licence fee to pursue their trade and needed to pass on their costs, decorative paper became an expensive purchase, and a rather prestigious one. To police payment of the taxes, government inspectors made a daily round of wallpaper makers, and stamped every sheet they produced as proof of payment. Our papers bear a Georgian excise mark with the relevant inspector’s number below the stamp.

There are other procedures to help us date wallpapers. Probably the most reliable is identifying the technologies used to make the paper. We need to distinguish hand-making techniques from machine processes and to recognise the differences between traditional block printing and machine-pressed decoration. We might also use changing taste or fashion in design as a guide; comparing newly found, decorated papers with other such work that is already safely dated, and we might consult period source books for corroboration. It is also particularly useful to be aware of any architectural changes to a building that might have taken place alongside changes in interior decoration.

In this instance, we can tell that we have sheets of handmade paper that have been hand block-printed and stencilled – they have not been near any machinery. We know too that there is a sheet of wallpaper with a foliate motif very similar to ours in the Victoria and Albert Museum, reckoned to date between 1715 and 1730. We understand also that our paper was found in the rather grand-looking corner house close to the museum on Olney Market Place.

This house was once the Catherine Wheel Inn, but it was bought by an Olney lace dealer – a dealer named Richards, one of the many traders who became rich on the backs of the local lace makers. In 1722, probably to celebrate and demonstrate his enhanced personal circumstances, Mr. Richards upgraded his house architecturally. There is evidence of this in its refaced walls and smart classical façade. It seems likely that our wallpaper dates from this time and formed part of some simultaneous, interior improvements.

Today the building is divided into two, numbers 37 and 38 Market Place

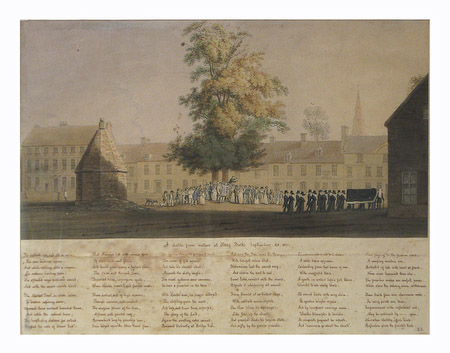

In this ink and watercolour, the Catherine Wheel is the building to the far right of the row of buildings with the church spire behind.

Local Housing

It is interesting to discover that in the eighteenth century Olney had at least one inhabitant with the wealth, and a property, that warranted this sort of fashionable treatment. From Cowper’s letters we tend to hear more about the poverty of the town, and about miserable living conditions. There is his reference for example to the ‘thousand rats’ which shared his servant Dick Coleman’s accommodation. This was the house next door to Orchard Side which is now part of the museum. Similarly, when Cowper leaves Olney for Weston Underwood in 1786 he says of his time here:

I lived longer at Olney than anywhere. There indeed I lived till mouldering walls and a tottering house warned me to depart.

But he also testifies to the town’s development architecturally, and attributes this to its successful lace trading and the new wealth of its lace dealers. For instance, in 1786 he writes about a house he has been looking at for his cousin, Lady Hesketh, and mentions its builder:

The man who built it is lately dead. He had been a common sailor…When we came hither he was almost penniless, but climbing by degrees into the lace-business, amassed money, and built the house in question.

Later he describes this dealer’s home in more detail:

The parlour is small and neat, not a mere cupboard, but very passable: the chamber is better, and quite smart. There is a little room close to your own for Mrs. Eaton, and there is a room for Cookee and Samuel…The kitchen is bad – it has indeed never been used except as a washhouse; for people at Olney do not eat and drink as they do at other places. I do not mean, my dear that they quaff nectar or feed on ambrosia, but tout au contraire. This abominable kitchen…is out of doors…no bigger than half an eggshell…

In another letter Cowper reflects further on the quality of Olney housing. He reports to Lady Hesketh:

Olney…though much improved since our first acquaintance with it, is rather a poor town, and contains but one house except our own, that is not occupied by a trade…But we are just now come home from such a one that is in many respects the very thing we wish…It has what may be called in the country a very good parlour, and very neatly furnished. Over it is a very good chamber, large and in good order; and in it a very good bed It has also a kitchen, roomy enough, with a good fireplace close to a good sash .window…there is also a pretty garden that has been famous in Olney these many years.

Eventually Cowper suggests Lady Hesketh lodge in the ‘smart stone building’ (the Vicarage) built by Lord Dartmouth in around 1768. Here he says she might enjoy good sash windows (very much the vogue) and a house where:

The parlour is so large that you might entertain a dozen persons in it with the utmost convenience, and the chamber over it is the same size.

In these excerpts Cowper describes quite a range of what he presumably deemed appropriate housing for gentlefolk. None of it sounds that grand and it is therefore particularly interesting to learn that our wallpaper was found in one of these houses: such papers were in the latest fashion and would have been very costly.

The wallpaper’s motifs

The motifs before us look Chinese, an impression confirmed if we look at the women with their distinctive costumes, hair-styles, postures and features. There are also the flowers, stylised lotus blossoms, to consider; these are shaped and draped in ways we probably recognise from Chinese ceramics or textiles; and there are the calligraphic ‘commas’ representing lotus leaves. The episodic, or random arrangement of the individual scenes also suggests Chinese work, as does the lack of Western perspective.

The other subject matter is also oriental in both treatment and choice: the single branches of fruit – plums or peaches – for example, with their three-dimensional leaves; the two ladies sitting about in a garden, perhaps tending or gathering their lotus blossoms while the young boy between them holds a sample; and we can almost see – despite the paper damage – another boy standing on a Chinese ceramic urn with a small dog jumping up beside him. (A motif, sometimes described as a begging dog, that is borrowed from Chinese ceramic work.)

The hint of architecture – presumably some kind of garden feature – is also a reference to a typical Chinese outdoor setting, one suited to leisure and contemplation. And finally there are the pools of shadow suggesting a stable space for these objects and people to inhabit.

The hint of architecture – presumably some kind of garden feature – is also a reference to a typical Chinese outdoor setting, one suited to leisure and contemplation. And finally there are the pools of shadow suggesting a stable space for these objects and people to inhabit.

For an English audience the symbolism of some of these wallpaper motifs was perhaps neither here nor there. The papers were after all probably regarded as mere ornament, a surface decoration, and not as Significant Art. However it might be of interest to know that in oriental artwork the lotus represented Buddhist thought; while a butterfly (appearing on one of the sheets of paper only) symbolised immortality, abundant leisure and joy to the Chinese. Where it was combined with a plum it signified longevity. (For the Japanese, by way of less happy contrast, a butterfly signalled a vain woman or a fickle lover.)

The printing and colouring processes

A paper-stainer would have prepared these papers by coating them with gesso (basically a thin coat of chalk and binder which acts as a primer) and a ground colour – in our case, a pale buff. Each sheet would then have been block printed by hand using wooden blocks and thin black ink. This would position the basic design in outline form. Finally these outlines would be filled in with thin watercolours applied through stencils. The stencilling is evident from the overlapping, or mis-positioning, of some of the colours – for example where they override the outlining black ink.

There are seven colours used on our papers – two pinks, two greens, a brown, a yellow and some white. This is a goodly number for an early example of wallpaper and, going by a comment made about the similar Victoria and Albert Museum specimen, would have made these papers even more expensive than those with a more limited colour range.

Paper sheets – singles and ‘pieces’

Our two sheets of paper are 24 inches (61 cm) wide and approximately 16 inches (41 cm) deep. The first wallpapers were made in single sheets like this – though the precise measurements of a single sheet seem to have varied a bit from production place to production place. Sometimes such papers were decorated and purchased singly, so the patterning within each needed to be complete, somewhat restricting their design.

Our two sheets of paper are 24 inches (61 cm) wide and approximately 16 inches (41 cm) deep. The first wallpapers were made in single sheets like this – though the precise measurements of a single sheet seem to have varied a bit from production place to production place. Sometimes such papers were decorated and purchased singly, so the patterning within each needed to be complete, somewhat restricting their design.

Papers like these might be applied one by one to a wall – perhaps pasted in a row to make decorative filling above a dado – with some careful overlapping at their thin deckled edges (the ruffled edges that are typical of hand -made papers) to mask the join. Single sheets might also be used as decorative touches to the insides of furniture or boxes.

The introduction of a kind of joined paper, whereby single sheets were pasted together before being purchased (in ‘quires’ or bundles of 24 sheets) and attached to a wall was quite a breakthrough; for it released the paper-stainer from such small scale designing and also helped purchasers to use the papers in other effective ways. This innovation is described in a text of 1699 by a John Houghton:

A great deal of paper is now a-days so printed to be pasted on walls to serve instead of hangings; and truly if all parts of the sheet be well and closely pasted on, it is very pretty, clean and will last with tolerable care a great while; but there are some other done by rolls in long sheets of a thick paper made for the purpose, whose sheets are pasted together to be so long as the height of a wall.

In fact the height of rooms was not critical to the production process as wall dimensions would obviously vary. But the standard measurements of a joined ‘piece’ (as a long length of wallpaper was called) was soon established at 12 yards by half an ell. These dimensions were familiar to early wall decorators as they were those already used for tapestry hangings. (By the way, the ‘ell’ was the supposed measurement of an outstretched arm, shoulder to wrist, and this had been standardised at 45 inches in England. An ell varied in length across Europe, sometimes, as in Denmark, featuring at a more sensible sounding 24 or so inches. The word ‘elbow’ is of course significant in all of this.)

It was usual to sell the main ‘piece’, or roll of a hanging alongside a separate piece with a matching border. These border edgings were used to cover joins or to act as framing devices for the main hanging or pattern, thus lending an eighteenth – century room a highly fashionable, panelled look.

Chinoiserie

Although we have described our papers from the perspective of their oriental ‘look’, we have not yet established that they are decorated in a style known as ‘Chinoiserie’. This is a style label given to work made either by Europeans in imitation of Chinese originals or by the Chinese in ways thought to appeal to a growing European market.

But how did this style begin?

There is some research suggesting early cross-pollination of designs moving from West to East rather than the more usual East to West. It points to evidence of architectural ornament passing from Greece to the Far Orient, as well as to some settling in the Middle East. The examples given are usually versions of Greek foliate designs, such as the rolling acanthus leaf, which have been seen replicated on early Chinese architecture. Other examples of organic forms traced to China via Persia and Greece are thought to have been copied from patterned silverware.

More typical however, is the research which traces a gradual flow of decorative ideas from East to West and which comments on the way such wayward ideas rumpled previously unquestioned norms of Western fashion and good taste. Eastern wares and Eastern designs provided the West with new things for the rich to buy, gratifyingly conspicuous, exotic consumables, and opened the door to challenging new designs.

An interest in the Far East – its products and ways of life – is supposed to have started with Marco Polo’s tales of his late thirteenth-century travels. But chiefly it is trade that is behind a flow of decorative imagery from East to West and it probably began with textiles. The famed overland silk route, developed during the fourteenth century, led to an increased familiarity with and interest in, oriental silk weaving and embroidery. From the silk trade, Chinese motifs such as fire-breathing dragons and exotic plumed birds gradually found their way into early Italian textile work

In the fifteenth century, with the addition of overseas routes, the range of Chinese imports increased to include more fragile wares such as lacquer work or blue and white porcelain. The latter was soon much imitated in both form and motif by European manufacturers. The blue and white tin-glazed earthenware of the seventeenth century (perhaps better known as ‘Delft’) made in the Netherlands, France and England is a key example. Such pottery was usually decorated to look as Chinese as possible with its Eastern landscapes and exotic flora and fauna. Fine Meissen porcelain wares were similarly influenced, with their renowned ‘Famille Rose’ decorations depicting Chinese flowers such as peonies and chrysanthemums.

In the fifteenth century, with the addition of overseas routes, the range of Chinese imports increased to include more fragile wares such as lacquer work or blue and white porcelain. The latter was soon much imitated in both form and motif by European manufacturers. The blue and white tin-glazed earthenware of the seventeenth century (perhaps better known as ‘Delft’) made in the Netherlands, France and England is a key example. Such pottery was usually decorated to look as Chinese as possible with its Eastern landscapes and exotic flora and fauna. Fine Meissen porcelain wares were similarly influenced, with their renowned ‘Famille Rose’ decorations depicting Chinese flowers such as peonies and chrysanthemums.

The range of fanciful motifs inspired by Chinese originals – pagodas, figures in exotic costume (often bearing an umbrella), craggy outcrops – on furniture, artefacts and interior design were so ubiquitous that they become a recognisable ‘style’ and mood. A further boost to its growth, if it needed any, was the popularisation of the style by Louis XIV of France (1638-1715). Indeed, the naturalism and swirling asymmetries of Chinoiserie were easily absorbed into the widespread eighteenth-century taste for ‘Rococo’– a style originating in France and characterized by lightness, elegance, and an exuberant use of curving natural forms in ornamentation.

While some eighteenth-century classicists might claim that Chinoiserie was

a ridiculous hodgepodge of serpents, dragons and monkeys

it is probably true to say that even the most understated neoclassical house would have a whimsically patterned fabric, ornate vase or garden folly tucked away somewhere on its premises.

Chinese wallpaper

There is a distinction to be made between Chinese papers and English papers ‘in the Chinese fashion’. It is generally agreed that the first examples of Chinese wallpaper (rather than the English-made Chinoiserie papers like ours) arrived here in the seventeenth century. It’s thought however that these early specimens were just gifts, made between merchants to conclude a transaction or mark a legal contract. Such single sheets of hand-painted paper were regarded by the Chinese as minor goods and were used by them somewhat infrequently – for example at particular ceremonies such as funerals – rather than as staples of tasteful interior decor. Nevertheless early travellers to China reported a use of plain papers – painted white, crimson or gold – hung on interior walls.

It was in South China that foreign visitors might have seen what inspired the beginnings of a trade in wallpapers: here it was customary to paste house windows with plain paper and sometimes to paint it decoratively. It is thought that European visitors’ obvious enthusiasm for such ornament might have prompted the Chinese to produce similar work for export.

The eighteenth century saw the grander Chinese papers being imported and used in the grander houses. These papers were typically hand painted throughout on a white mulberry or bamboo fibre paper, though a detail – foliage perhaps – might be added with small printing blocks. In many cases the paper was coated with a white pigment, sized and then dusted with mica. The idea was partly to give the paper a sheen so that it looked more like silk and partly to improve the paper’s smoothness, whiteness and uniformity as well as to prevent over-absorption of ink. It was usual to lay on a black outline of the design first and then fill this in with colour; these colours were mineral pigments bound in animal glue and sometimes just applied to the back of a paper to give a translucent effect.

The imported designs often depicted vast panoramas: scenes of magnificent mythological events or other such narratives, or else they formed huge rural landscapes. More rarely Chinese paper panels arrived as single framed sheets of different sizes, each with a distinctive, separate motif. These were then assembled in patchwork on a house wall. More usually Chinese papers were supplied in long rolls or panels, numbered in the sequence to be hung, and sold in sets. The papers were trimmed by the purchaser to fit his walls and spare bits used to make repairs, hide faults or joins and otherwise enhance the overall effect.

Whichever version was employed, entire rooms of historic houses were transformed into something very new, challenging and distinctly foreign. These were sophisticated schemes of artwork which looked very different to the printed repeat patterns seen on European papers.

Textile influences on wallpaper

A huge influence on the design and use of European wallpaper came with the import of oriental textiles. These included the remarkable hand-printed calicos known as ‘Chintz’ – cottons imported by the East India companies, for the major part from India, but also from Persia and China. By the early seventeenth century (1631 in fact) the English East India Company was licensed to import chintz into Britain and traditional eastern block-printed or hand-painted designs became vastly popular. This work, most of it from Rajasthan, incorporated such motifs as the ‘Tree of Life’, lush blossom and fruit, rambling foliage, birds and insects. The cottons so designed were used both for dress materials and as furnishing fabrics; they became such a successful commodity that their import threatened the livelihoods of English wool and silk weavers.

A huge influence on the design and use of European wallpaper came with the import of oriental textiles. These included the remarkable hand-printed calicos known as ‘Chintz’ – cottons imported by the East India companies, for the major part from India, but also from Persia and China. By the early seventeenth century (1631 in fact) the English East India Company was licensed to import chintz into Britain and traditional eastern block-printed or hand-painted designs became vastly popular. This work, most of it from Rajasthan, incorporated such motifs as the ‘Tree of Life’, lush blossom and fruit, rambling foliage, birds and insects. The cottons so designed were used both for dress materials and as furnishing fabrics; they became such a successful commodity that their import threatened the livelihoods of English wool and silk weavers.

The brilliance and fastness of the colours produced on seventeenth-century chintz were its main appeal. Indian craftsmen and women had practised the art and science of dyeing with natural ingredients for years and were highly skilled at it. In England by way of contrast there was a very limited tradition: Tudor painted cloths were crude by comparison, produced by daubing semi-raw pigments onto linen and making colours which were both dull and short-lived.

The market for chintzes also developed due to the increasing demand for fabrics in the home. By the seventeenth century the bedstead – commonly recognised as the most prized household possession – was usually decorated with a hanging made of patterned fabric. Once this had become an accepted part of fashionable décor, house owners began to add further comfort and softness with fabric-covered cushions and perhaps coverlets for their parlour stools. So Indian painted and printed calicos filled an important gap in the European fabric market; theirs was a product the West could not at first match.

The market for chintzes also developed due to the increasing demand for fabrics in the home. By the seventeenth century the bedstead – commonly recognised as the most prized household possession – was usually decorated with a hanging made of patterned fabric. Once this had become an accepted part of fashionable décor, house owners began to add further comfort and softness with fabric-covered cushions and perhaps coverlets for their parlour stools. So Indian painted and printed calicos filled an important gap in the European fabric market; theirs was a product the West could not at first match.

By 1640 imported chintz had become a major branch of the East India trade. From inventories we know that the walls of whole rooms might be decorated with this fabric and also fitted out with matching soft furnishings. Eastern imported cottons became so popular in fact, that the trade in coloured calicos was banned in 1700. This was just a temporary set-back at first, as loopholes were quickly found and the tax evaded; and even after the law was tightened in 1722, effective smuggling kept the imports coming. However, the trade in painted and printed cottons from the East gradually declined in the eighteenth century as Europeans developed better, and relatively cheap techniques of their own.

It is into this context – the desire for, and use of decorative cottons to decorate rooms – that we need to set the work of our eighteenth-century paper-stainer. And it was not just chintzes that designers turned to for inspiration for their patterned papers, but also to other fabrics; those produced at home with an established pedigree and popularity. For example, they copied tapestries, lace and embroideries. The first wallpaper makers would often imitate such familiar crafts: they occasionally attempted to depict the grand woven scenes on English or Flemish woollen tapestries (already popular as hangings in the wealthier homes); or they turned to lace motifs, such as tiny flowers and leaves and scrolls; originally worked by bobbin or needle onto net; these made good, small, easily repeated designs. Similarly, early paper-stainers liked to reproduce the Elizabethan flowers, leaves and insects known from stumpwork and from delicate blackwork stitchery, and they clearly found a market for such translations.

The cross-fertilisation between textiles and paper, particularly when applied to ornamental furnishings, tells quite a tale as first one then the other dominates. And the interchange continues today, prompted as ever by the desire for the new and the cutting edge, and encouraged by new technologies.

Paper making

We noted at the start that our papers were handmade and perhaps it would be interesting to know a little more about this process.

Early papers like ours were made of rag fibre – cotton rags that have been pulverised. For fine wallpapers it was important that the original materials were carefully sorted and only the whitest used for best quality white paper. After washing, the rags would be broken up in water and mashed to a pulpy fibre before being further diluted and turned into a milky looking fluid. At this stage a framed net (a mould) is inserted into the thin, gruel-like liquid and then carefully lifted out to drain off the water. This allows a thin layer of fibres to spread themselves smoothly on the surface of paper-maker’s net or wired mould. And this is the paper sheet to be.

To remove the sheet of paper the mould is turned and the wet layer of fibre pressed onto a waiting cloth. As the frame is lifted away a ‘deckle edge’ – the slightly raggedy finish to a hand-made paper – is formed. Several sheets are stacked up in this way – laid one on top of the other – to form a pile or ‘post’. This is pressed to get rid of more of the water before the individual sheets of paper are separated and hung out to air dry. Recognising handmade paper involves noting the deckle edge, the lines of the wire work impressed into the laid fibres from the mould and – under a microscope – the random dispersion of fibres.

A note on repairs

When these two sheets of paper arrived in the museum they were very dirty – almost black – as well as torn. To clean them we used a special sponge to lift off the surplus filth. We then tested a small part of the artwork to check for stability and found we were able to wash the papers gently with water and brushes.

Next we began to repair the worst tears by pasting them together with very fine Japan (tissue-like) papers. The paper had become very weak and soft – rather like blotting paper. It needed re-sizing. As a further stage in repair, and with the help of modern copying techniques, we may try to ‘fill in’ the missing sections. But obviously this will only be viable where there is an appropriate bit of imagery in an original to copy.

Incidentally, this repair process reminds me of one way people used to avoid the Georgian decorated paper tax mentioned earlier. If purchasers bought their paper plain, and pasted it on their walls as it was, they could then prime and decorate it themselves, with blocks or stencils – much as the paper-strainer proper would do. Since plain paper was not taxed this was an excellent ruse, and {we are told).one much employed at the time.

Incidentally, this repair process reminds me of one way people used to avoid the Georgian decorated paper tax mentioned earlier. If purchasers bought their paper plain, and pasted it on their walls as it was, they could then prime and decorate it themselves, with blocks or stencils – much as the paper-strainer proper would do. Since plain paper was not taxed this was an excellent ruse, and {we are told).one much employed at the time.

Further Reading

From East to West. Textiles from G.P. and J. Baker, catalogue of an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, 9 May to 14 October 1984, Baker/ V.& A. Publishing, 1984

Elliot, Marion, Paper Making (Contemporary Crafts Series), Letts, 1994

Hoskins, Lesley (ed.), The Papered Wall. History, Patterns and Techniques of Wallpaper, Thames and Hudson,1994