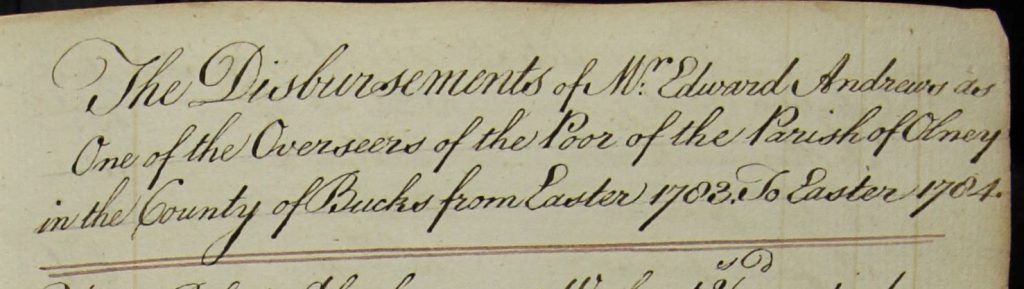

Within the Poor Laws records in the Museum Archive there is also a small book which gives insights into the Roundsman system of poor relief.

There have always been poor people who needed help or charity to survive. Before King Henry VIII seized all the monasteries in England in the 1540’s, these religious centres had given food to the poor to help them cope.

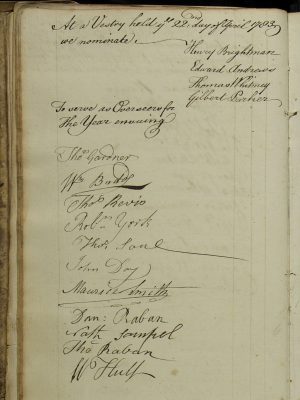

In 1601, the Elizabethan Poor Law was introduced, which required each parish to support its poor inhabitants with both money and goods. The parishes appointed Overseers of the Poor, who would be four local better off residents who would each serve for three months and administer the support to the needy residents.

(Click on the image to enlarge)

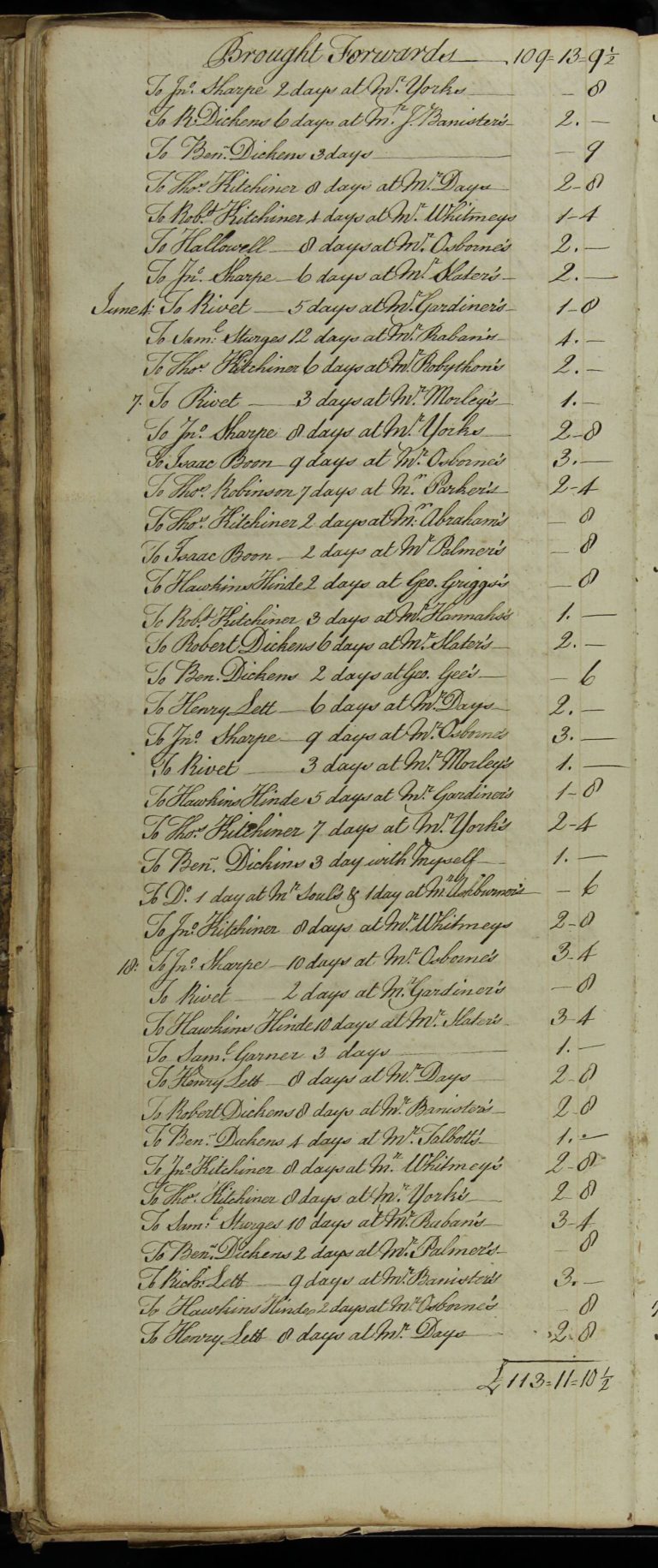

As a way to reduce costs, the Overseers would offer the labour of benefit recipients to potential employers in the community at a price agreed between the Overseers and the potential employer. Sometimes, an auction was held to get the best price for the available labour. The pay given to the employees was not based on the value of the work done, but rather on the prevailing price of bread and the number of dependents being supported by the employee.

In 1749, resident claimants were receiving six pence a week for each adult, but by 1800 this had risen to twelve pence a week. There are regular entries for these payments throughout the Poor Law books. For example we can see that in 1783, the employees were paid four pence a day on top of their weekly benefit.

Examples from this page:

For John Sharpe 2 days at Mr York’s 8d

R Dickens 6 days at J Bannister’s 2/0d

Thomas Kitchener 8 days at Mr Day’s 2/8d

Robert Kitchener 4 days at Mr Whitmey’s 1/4d

Hallowell 8 days at Mr Osborne’s 2/0d

John Sharpe 6 days at Mr Slater’s 2/0d

Rivet 5 days at Mr Gardiner’s 1/8d

Samuel Sturges 12 days at Mr Raban’s 4/0d

Thomas Kitchener 6 days at Mr Robython’s 2/0d

Hawkins Hinde 2 days at George Grigg’s 8d

In these cases, the Overseers might have done a deal to supply the labour at five pence a day, but given the employees four pence, keeping the penny to help their funds.

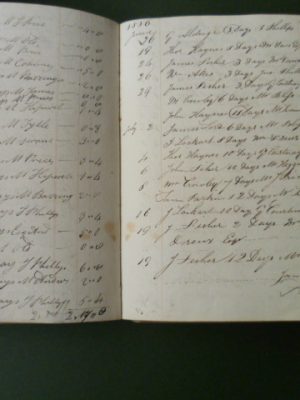

We also have a Roundsman’s Book covering 1810 to 1819, which has a page for each employer showing who worked for him and how much the Overseers paid to each employee. This image shows the page for Mr Higgins. (Click on the image to enlarge)

A John Higgins was born in Weston Underwood, a village about a mile from Olney. Later he inherited Turvey Abbey.

We do not know if they are one and the same but this article tells you more about the friendship between John Higgins of Turvey Abbey and William Cowper.

Later records show the rate had gone up, so John Lockwood received eight pence for working for one day for M Old, and G Aldridge received sixteen pence for working for two days for Mr Hipwell. (Click on the image to enlarge)

The employees would be given a ticket by the Overseer, showing who they were to work for, which they would present to the employer. When the agreed work was done, the employer would sign the ticket, which the employee then took back to the Overseer to qualify for extra pay. This system was known as the “Roundsman” or “Ticket” system, for obvious reasons.

By the 1820’s, this was felt to be very unfair to the independent labourer as the rates of pay usually undercut their rates.

The new Poor Law of 1834 scrapped the roundsman system, requiring the very poor to reside in the workhouse and carry out usually menial work given to them.

The Cowper & Newton Museum holds these records. Most of the Poor Law books have been digitised and can be searched using a memory stick sold by the Museum. So far, the Roundsman’s Book has not been digitised.