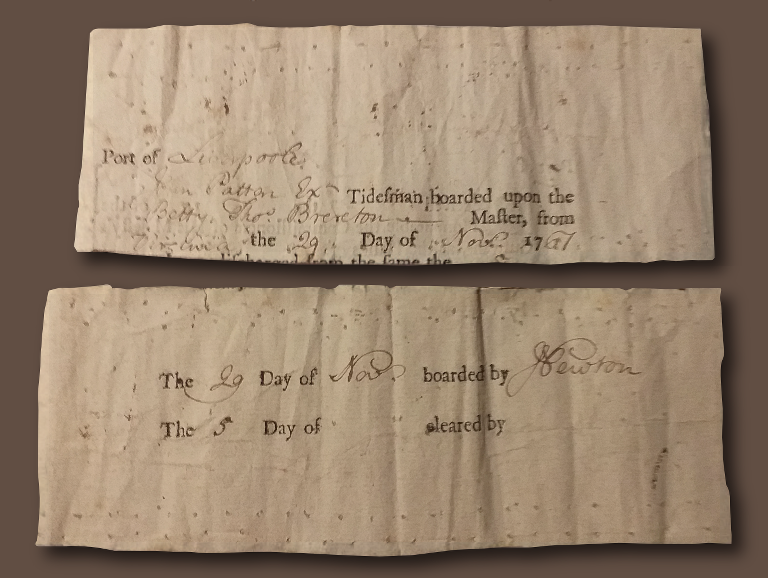

When the Cowper & Newton Museum shared with us a photograph of a small paper exhibit from its collection – a boarding docket from John Newton’s time as a tide surveyor (1755-1764) in Liverpool – we didn’t think we would be able to unlock its secrets because there wasn’t that much information listed on it.

It noted the name of the ship that Newton had boarded, its port of departure and arrival, its master, the name of the executing tidesman who had accompanied Newton aboard the vessel, and the number of days that ship had to be cleared by. The date of the docket, with Newton’s signature beside it, was recorded as ‘the 29 Day of Nov., 1761’, a Sunday.

But not only has the research helped to uncover more information about the docket, it has also helped gain more insight into Newton’s role as a tide surveyor in the port. We hope you find it interesting.

Liverpool, the Port Town

Newton was already familiar with port when he accepted the role of tide surveyor in 1755. It was seven years since he arrived on the quayside from his storm damaged rescue ship, Greyhound, in 1748. The town which embraced him and offered him employment had recently overtaken the two port cities of London and Bristol in the transatlantic slave trade (1740s), but by the time of Newton’s tenure, as tide surveyor, its meteoric economic rise was about to stall.

Newton’s new career began on the eve of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763). There were already tensions at the port because of ‘the want of seamen for the speedy manning of the fleet now fitting out’ for King George II’s Navy and, on 24 March, 1755, the Corporation passed a resolution for the impressment of the town’s sailors, on ‘account of the French Having Attacked His Majesty’s Dominions in America’.

As well as global threats, the Port of Liverpool, in recent years, had to overcome the natural challenges that the River Mersey presented to its growing trade in shipping, which Newton was already familiar with. In a contemporary account, Samuel Derrick, in a letter to the Earl of Corke, dated August 2, 1760 explains the dangers it posed:

‘Liverpool stands upon the decline of a hill, about six miles from the sea. It is washed by a broad rapid stream called the Mersey, where ships lying at anchor are quite exposed to the sudden squalls of wind, that often sweep the surface from the flat Cheshire Shore on the west, or the high lands of Lancashire that overlook the town on the east; and the banks are so shallow and deceitful, that when once a ships drives, there is no possibility of preserving her, if the weather prove rough, from being wrecked, even if close to the town.’

Letters Written from Leverpoole… by Samuel Derrick. pub. 1767 [with standardised spelling]

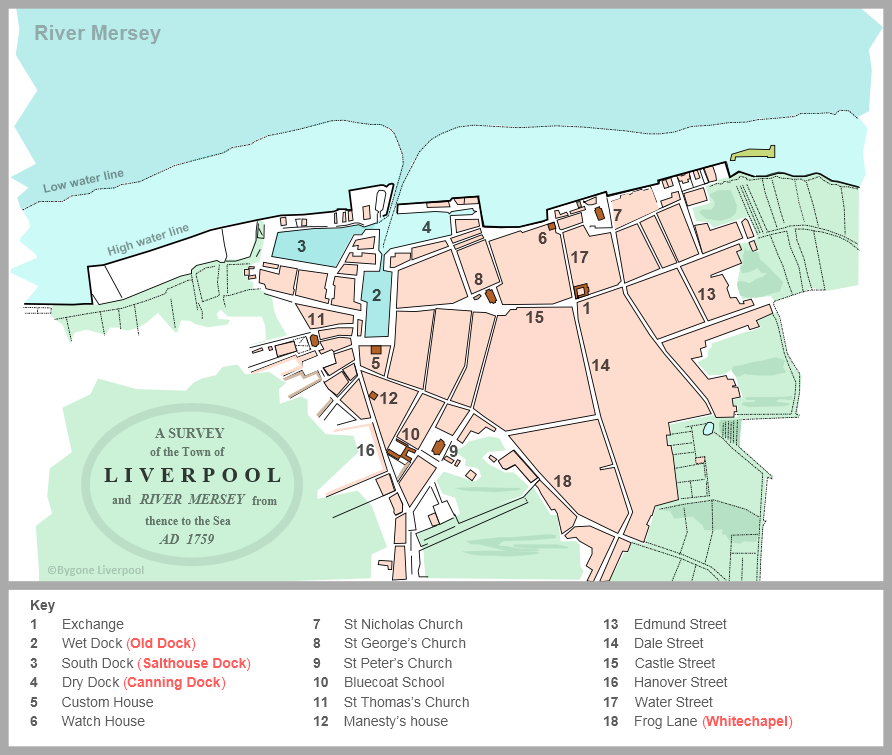

To overcome the natural limitations of the Port, Liverpool merchants, through the town’s Corporation, decided to build a safe refuge for its shipping: a commercial wet dock.

By 1755, the town had two wet docks: the Old Dock, 1715; and the South Dock (Salthouse Dock), 1753. It also had a tidal basin called the Dry Dock (later renamed Canning Dock), 1739, for receiving coastal traders, fishing smacks and other smaller vessels in. It further provided access to two graving docks—used for ship repairs and careening vessels.

A new career beckons: John Newton, Tide Surveyor of Liverpool

John Newton’s mentor and employer, Joseph Manesty, managed to secure a new position for him following his seizure. Newton had described his sudden (but not repeated) illness as an ‘apoplectic fit’—which happened just before Newton was due to embark on Manesty’s ship, the Bee, bound for Africa. It marked a shift between his two Liverpool careers, from a former slave ship captain to a tide surveyor.

Newton’s first day of work was Monday, 18 August, 1755, which he summarised in his diary below. It was also exactly two weeks since he had celebrated his 30th birthday.

‘Monday 18th August. Entered upon my new office went down the River, in the afternoon spent an hour or two upon the Rock Hills with Mr W…’

Lambeth Palace Library – MS 3790

Two days later, Newton wrote a letter to his wife, Mary (Polly) on Wednesday, 20 August – explaining his new responsibilities to her.

‘My duty is to attend the tides one week, and visit the ships that arrive, and such as are in the river, and the other week to inspect the vessels in the docks, and thus alternately the year round. The latter is little more than a sinecure, but the former requires pretty constant attendance, both by day and night. I have a good office, with fire and candle, fifty or sixty people under my direction, with a handsome six-oared boat and coxswain, to row me about in form.’

Letters to a wife…v.2 Printed by J. Johnson, 1793

What exactly did a tide surveyor do? A tide surveyor was a customs official, an exciseman who *surveyed the tides* looking for new shipping arrivals on the river with the intention of boarding them. Tide surveyors were assisted by a number of tidesman (and boatmen) who were responsible for watching a ship’s cargo until it could be landed on a ‘legal quayside’. An excise duty, on behalf of the Crown, was then calculated and subsequently paid for by the ship’s owner.

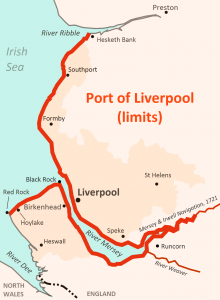

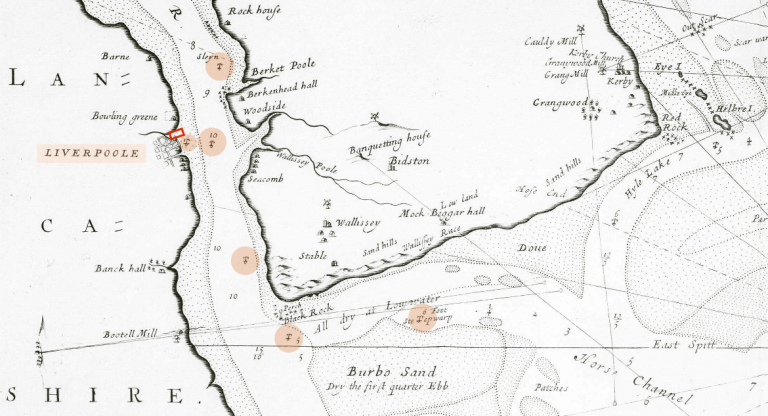

The Port of Liverpool* limits were described in an account from 1723. They extended from the Red Stones (also known as ‘Red Rock’) at the mouth of the River Dee to Hesketh Bank, at the mouth of the River Ribble, by Preston. It also included the rivers Mersey, Weaver and Irwell.

* The ‘Port of Liverpoole’ is also listed on the C&NM docket.

The King’s “legal quays”. All shipping goods coming into or out of the Port of Liverpool (the area marked red on the map) had to pass through Liverpool first, at a recognised legal quay, for the purpose of customs’ collection. Historically, they were located within a 500 yard strip of the town’s riverside frontage—from ‘Red Cross Street Southerly’ to ‘Shilly Patch’ (marked by a limestone perch) – an area just north of Chapel Street; and by 1723, the Old Dock quays were included, following completion of a new custom house at the east end of the dock which opened in 1722. It was prohibited to land elsewhere in the port:

‘We do hereby and by virtue of the said Commission utterly prohibit disannul make void determine and debar all other places within the said Port of Liverpool from the privilege right and benefit of a place key or wharf for landing or discharging loading or shipping of any Goods Wares and Merchandizes as aforesaid except as in the said Commission is excepted.’

The Customs Collection of the Port of Liverpool, by Arthur Wardle, 1946, HSLC paper

However, in 1726, just three years after the Commission issued their prohibition, they made this observation.

‘For instead of confining their shipments of tobacco and “debenture goods” to the legal quays, some of the exporters perform it on the other side of the town, where the ships lie ” on the sands ” a mile from the Custom House. The merchants have to bring the goods to the scale, in the Custom House yard to be weighed, but there is much difficulty afterwards in witnessing shipment, and Tidesmen have to be put in charge of them during transit from scale to export ship. Collector thinks all ships should be compelled to use the legal quays’

Customs letter-books of the port of Liverpool, 1711-1813. R.C. Jarvis. HSLC paper

The challenge that Newton faced as a Tide Surveyor

If new shipping to the port arrived outside of high water, they would normally drop anchor in or on the approach to the Mersey first, and then wait for flood tide to come in, when the town’s two wet docks would open their gates. Rough weather, a head wind, or no wind at all could also stop a ship’s progress from coming to an approved place of landing, a delay that, in the eyes of King’s excisemen, provided ample opportunity for illegally running goods ashore. This was a practice that Newton’s colleagues in London expressed some concern about:

‘The excise commissioners glumly wrote in 1783 that as soon as a ship took moorings in the Thames, ‘the places near which they lye, are crowded with smugglers of every Description, as people resorting to a Fair, and the River is covered with Boats day & night watching the Opportunity to convey Goods out of every port-hole of the Ship.‘

Customs and Excise: Trade, Production, and Consumption in England, 1640-1845, By William J. Ashworth

It was therefore essential that any new arrivals to port (anywhere along its limits) were watched from land—either by riding officers* and tidesmen or from on board ship, by tide surveyors and tidesmen, to discourage any smuggling activity. In 1767, a tidesman colleague of Newton’s at Hoylake, also within the Port of Liverpool, positioned himself in the sand hills to do just that:

* Riding officers were excisemen on horseback who patrolled the ports coastal limits on land.

‘When any vessell is performing quarantine at Hoylake, the Tidesmen and Boatmen there do alternately watch in the sand hills day and night to prevent any goods from being run or any of the marriners making their escape from the vessell before the time of performing quarantine is expired.‘

Customs letter-books of the port of Liverpool, 1711-1813. R.C. Jarvis. HSLC paper

The Cowper & Newton Museum collection exhibit

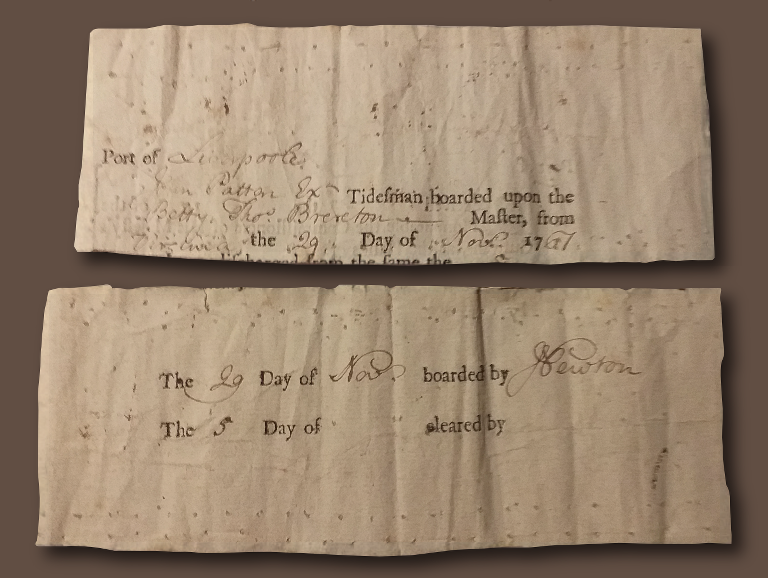

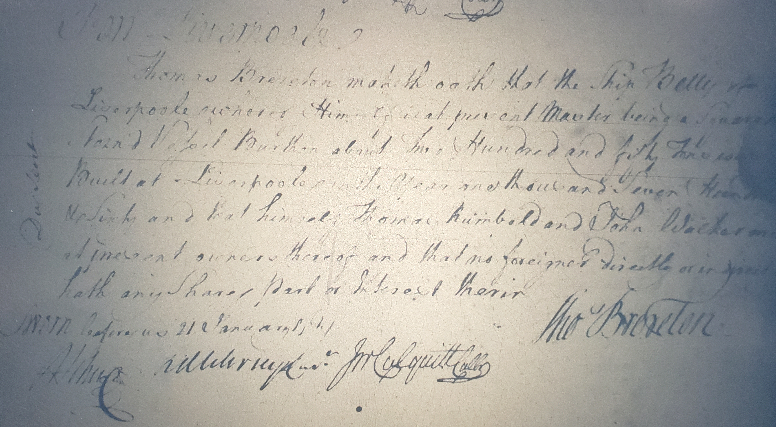

Returning to the C&NM’s manuscript exhibit for a more detailed look at its text, we find that, in summary, John Newton (Tide Surveyor) boarded a ship named the Betty from Virginia on 29 November, 1761, at the ‘Port of Liverpoole’. The ship’s master was Thomas Brereton. Also, another customs official, ‘John Patton, Ex – Tidesman’ (Executing Tidesman?) accompanied Newton on board. The bottom line lists – ‘The 5 Day of … cleared by’ – presumably, the time given to clear the ship’s hold of its cargo.

Port of Liverpoole

John Patton Ex- Tidesman boarded upon the

Betty. Thos. Brereton. Master, from

Virginia, the 29 Day of Nov. 1761

The 29 Day of Nov. boarded by J Newton [signed]

The 5 Day of cleared by

The challenge at this stage was to find anything we could on Thomas Brereton and John Patton, who were then unknown to us, and about the ship, Betty, from Virginia. We also wanted to find supporting evidence confirming the ship’s arrival in Liverpool, and, in addition, what could be learned from studying the men’s occupational roles on board the ship, which may help explain their duties and provide the context for the Cowper & Newton Museum docket signed by Newton.

Any other supporting evidence of Betty in Liverpool?

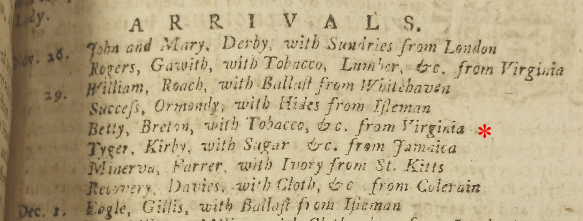

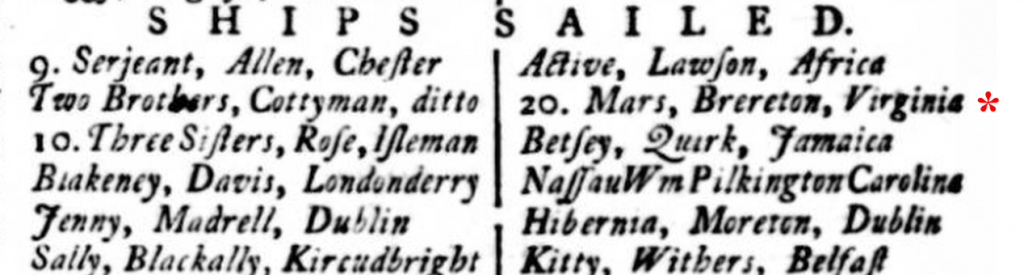

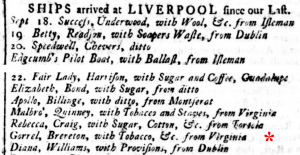

The first thing we did when we received the docket images was to check the local Liverpool newspaper archives to confirm the arrival of Brereton and the Betty – as a way of cross-checking the date on the C&NM docket. Our research turned up two results:

Newspaper clipping #1 – the Betty arrived on the Mersey (or in dock) 29 November, 1761 – matching the date listed on the C&NM docket. It also confirmed that her main cargo was tobacco from Virginia. Another five ships arrived with her that day: William, Success, Tyger, Minerva, and Recovery.

The clipping extract reads: ‘Betty, Breton, with Tobacco, & c. from Virginia’

Newspaper clipping #2 – the arrival of Betty in Virginia was also reported four months earlier in a Liverpool newspaper on 31 July, 1761. The record of her outward voyage from Liverpool was not listed.

The clipping extract reads: ‘Virginia. Arrived from Liverpool the Betty, Brereton.’

Tide Surveyor & Tidesman duties on board Betty

The C&NM docket – we believe is written in John Newton’s hand and also carries his signature. It lists the name of Newton’s colleague, who accompanied him on board the Betty to inspect her cargo of Virginian tobacco, as ‘John Patton, Ex – Tidesman’. We couldn’t find any information on Patton himself, but his presence on board ship, on the first day of arrival at the port, suggests that both men boarded on the river rather than in dock.

Tide surveyors and tidesmen normally met ships on the river, to reduce the risk of smuggling (the running of goods), as previously mentioned, and were collectively known as the Water Guard.

In a near contemporary account, written 10 years after the Betty arrived at Liverpool, William Hunter, a Tide Surveyor of the Customs in the Port of London, offers some insight into the duties and responsibilities of a Tide Surveyor and Tidesman when on board a ship.

[Extracts from The Tidesman’s and Preventative Officer’s Pocket-Book, by William Hunter, Tide Surveyor of the Customs in the Port of London, 1771]

‘When a ship first enters within the limits of any port, the tide-surveyor… is to take proper care, to place a sufficient number of tidesmen on board, in order to prevent the fraudulent landing and conveying away any part of the goods imported from foreign parts, and for which his Majesty’s duties have not been paid or secured, the tide surveyor is also, at the same time, diligently and carefully to rumage (sic) her, and when he has performed his duty and is satisfied, before he leaves the ship he must deliver to one of the tidesmen a blue book, as also a lanthorn [lantern], remembering that no officer may go into the hold or between decks with a candle, unless secured in a lanthorn, and they are to continue on board, watching constantly, as well by night as by day, by turns, upon deck, walking to and fro, and never leaving the same unguarded.‘

After boarding Betty, Newton would have handed a blue book* to his (Executing)** Tidesman, John Patton, who in addition to his duty to watch the vessel, also had to supervise the unloading of her cargo on to a legal quay, where it would be received by a landwaiter. The Betty was probably too large a vessel to be moored in the Old Dock; she may have been stationed either at the South Dock (Salthouse Dock) or at a quay fronting the river. Alternatively, if unloading took place from the River Mersey (which larger tobacco ships sometimes did) the cargo would then be transferred on to a lighter*** and then ferried to the correct and legal quayside.’

* A ‘blue book’ was a ledger, an account book used to record (itemise) the cargo removed from a ship.

** ‘John Patton’ Ex. Tidesman’ is recorded on the C&NM docket slip.

*** Lighter – a flat bottomed barge used for transporting cargo ashore.

‘The tidesman who keeps the blue book is to enter each day’s delivery, and when the tide surveyor comes on board, either by day or night, he is to mention the same in the book… the tidesman who keeps the blue book is looked upon to be the principal officer on duty on board, therefore, when the ship is at work he is carefully to enter the particulars of each days delivery, by inserting the marks, numbers, and outward packages of the goods, whether by tale, measure & Co. or other circumstances, attending the delivery of the goods out of the ship, which is never to be delivered but by an order under the hand of the landwaiter appointed to see the ship discharged.‘

‘Ex. Tidesman, John Patton’ was probably the *principal officer* on board the Betty. He may have been assisted by one or more tidesmen. A landwaiter was another customs official, assigned to the ship, who received the goods landed on the quayside. He also kept a corresponding blue book to record receipt of them. Both blue books had to tally up with each other when the vessel was fully discharged, ensuring that the cargo unloaded from the vessel matched the quantities of cargo landed on the quayside. A double-entry system of bookkeeping made sure that nothing went astray.

‘It is also the tidesmans duty to examine or search all persons gong over the side of the ship, and if any goods are found in their possession to stop them… they are not to permit the packages of any goods to be opened on board, nor the working or delivering of any goods in the night-time, nor any goods whatever to be unshipped at any time though with intent to be carried to the lawful key, without a note from the landwaiters as before mentioned.’

Working at night was not permitted, meaning that the vessel could not be unloaded at night. The tidesmen’s role now switched to being more of a watchman. Liverpool tidesmen were frequently criticised by the London Excise Commissioners for stealing sugar and tobacco, disappearing from their posts, or sleeping below deck, when they should have been standing guard on deck. It was the tide surveyor’s responsibility to check on them periodically to make sure they were still on duty. Tidesmen stayed with a ship until all cargo was fully discharged (often done in shifts).

[Once] ‘the ship is delivered [unloaded], which is to be signified to the tide surveyor for the station, who will come on board and clear and clear her, by rummaging, in the presence of the tidesman, to see if there are no goods concealed in any secret places, and if he finds no goods or merchandizes remaining on board concealed and not reported, he is to discharge the tidesman.‘

The reason for Newton’s preference to ‘inspect the vessels in the docks’ – on his land-based week – rather than to patrol on the river is perhaps less ambiguous now. With ships locked in dock, Newton needed only to check that his tidesmen were still on duty and that they were coordinating the unloading of ships by day; or at night, to ensure they were still at their post. Although Newton was expected periodically to rummage through a ship’s hold as cargo was released from it, when it was unloaded on to the quayside, it was a far easier task for him than policing the river for new arrivals, affording more opportunity for private study and meditation back in the Watch House.

The Tidesman’s and Preventative Officer’s Pocket-Book, by William Hunter, Tide Surveyor of the Customs in the Port of London, 1771

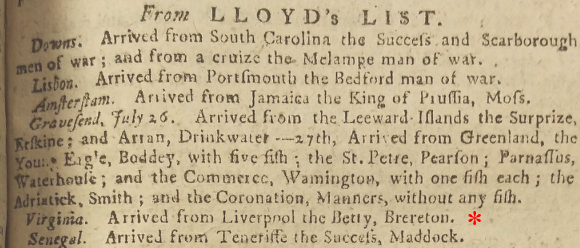

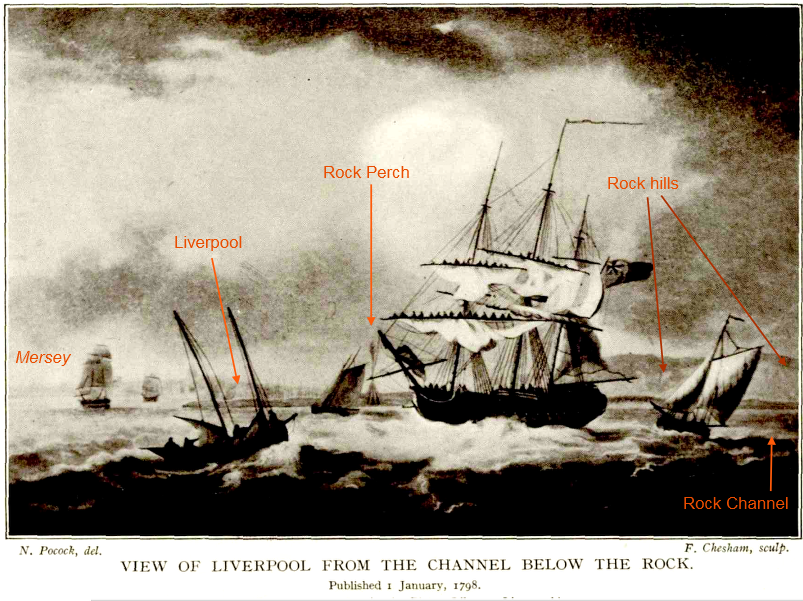

Surveying the tides: the River Mersey

When Thomas Brereton, master of the Betty, entered the Mersey in 1761 – he would have had to negotiate around the infamous Rock. A wooden perch (seen below, left) had marked a hazard to shipping since 1683. It was also one of the first navigational aids to be erected in the Port of Liverpool.

This is the same Rock that Newton visited on his first day as Tide Surveyor, on the river, Monday, 18 August, 1755.

‘Mr W. went with me on my first cruize (sic) down to the Rock. We saw a vessel, and wandered upon the hills, till she came in. I went on board and performed my office will all due gravity. And had it not been my business, the whole might have passed for a party of pleasure.’

Letters to a wife…v.2., printed by J. Johnson, 1793

The Rock hills – The hills referred to in Newton’s diary as ‘Rock Hills’ (capitalised) probably had an eponymous connection to the Rock, the notorious shipping hazard at the mouth of the River Mersey; rather than being named after a particular set of rocky hills. They were likely to be on the site of New Brighton today.

The Rock – has had several names throughout its history: Black Rock, Black Rock perch, Rock Point, the Rock, and Perch Rock. It was located at the entrance to the Mersey, three miles north of Liverpool.

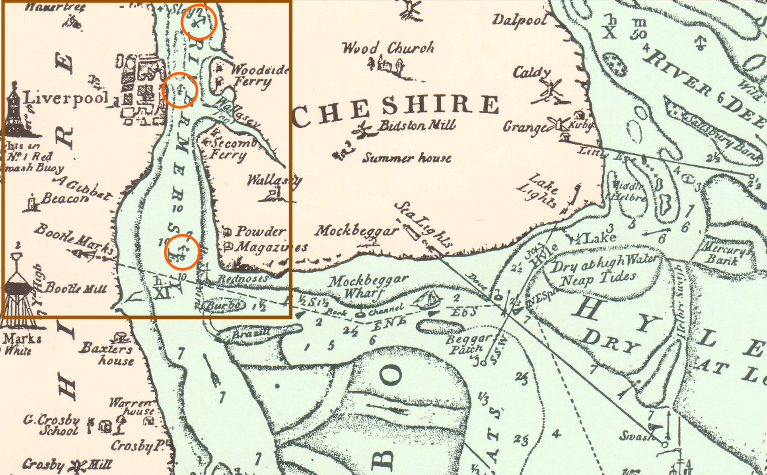

The anchorages highlighted below were the principal ones that Newton attended to as a tide surveyor – and also our three main candidates for where Newton and Patton boarded the Betty.

The first accurate map we have of the Mersey is Captain Greenvile Collins’ 1689 chart. It’s oriented for the seafarer approaching the Mersey, and so appears up-side down compared with modern maps of the area. ‘Black Rock’ and its perch are both noted – just above left where it says ‘Burbo Sand’ by the Mersey estuary. Interestingly, a similar hazard called ‘Red Rock’ is located on the opposite corner of the Wirral headland at the River Dee estuary. It also marks the start of the Port of Liverpool limits.

The anchorages (highlighted) as they appeared in 1689. Also note the ‘sand hills’ above Black Rock. On Williamson’s later 1766 map, the two bottom anchorages are absent from it, presumably silted up by then.

The Rock Channel – during Newton’s time at Liverpool, the main approach to the Mersey was through the ‘Rock Channel’ (the horizontal channel beneath where it says ‘Mockbeggar Wharf’). Ships, once they reached the end of the channel, had to turn a sharp 90 degrees right to enter the Mersey. If a wind was blowing from the south, or there was no wind at all, it stopped their progress, forcing them to anchor, as demonstrated in the account below:

‘We proceeded up the river Mersey, on which Liverpool stands, but the wind being very light we were unable to bring the ship up to the town, and were obliged to drop anchor just within the rock. We were immediately visited by the custom house officers.‘

A journal of travels in England… in the years of 1805 and 1806, by Benjamin Silliman. pub.1820

Note that the ‘custom house officers’ boarded immediately once the ship dropped anchor in the river – ‘just within the rock’ – which is the bottom anchorage ringed red (below).

The Liverpool Haven? The same anchorage by Black Rock is also shown on Yates & Perry’s 1769 map (below) drafted only 5 years after Newton had left Liverpool.

Ships attempting to leave the Mersey would also seek refuge here if the wind wasn’t favourable. John Newton when he was captain of the Duke of Argyle was stuck here for 10 days, from 11th – 20th August, 1750, unable to leave the river and turn westward due to the force of the south-westerly gales.

‘Saturday 11th August. Close weather, fresh gales between the South and West. At noon cast from the pier head at Liverpool, run under the topsails against the flood, at 3 p.m. anchored at Black Rock with the B.B…’

‘Monday 13 August. ‘In the afternoon a pilot boat brought our powder on board.’

The Journal of a Slave Trader, by Bernard Martin & Mark Spurrell

Delivering gunpowder to ships in Liverpool docks was banned in 1746. The magazine site at Liscard wasn’t purchased by Liverpool Corporation until 1752. Pilot boats probably ran a service supplying powder direct to ships which lie at anchor there, either supplied from Liverpool or from ad-hoc premises close to Liscard.

The anchorage was located in between 7 – 10 fathoms of water just off the Powder Magazines on the Cheshire shore at Liscard, also described by Newton on his last voyage on board the African returning to Liverpool, Aug. 29, 1753 ‘…and about 8 anchored at the Black rock with the best bower in 9 fathoms.’

In William Moss’s Liverpool Guide, 1796.

‘A little on this side the Rock, may be seen the Powder Magazines; where all the gunpowder for use of the ships, and other purposes are kept. They are placed at that distance (about three miles) to prevent bad consequences to the town in case of accident… Ships often lie off there at anchor, sheltered from the westerly wind, under high land, waiting for a fair wind to proceed to sea.‘

Newton may have spied the Betty from the Rock hills that overlooked the anchorage. It would have also given him the best vantage point to check ships approaching in the Rock Channel.

The site of the anchorage next to Black Rock is now silted-up since the groynes were added (river defences to reduce longshore drift and to trap sediment).

The Rock today – with New Brighton Lighthouse and the Mersey estuary in the background. We are not sure why it was called “Black Rock” – the sandstone colour is somewhere between pinkish-brown and taupe. It could be reference to the dead seaweed that dried on top of it or perhaps simply named because it was a deadly hazard to shipping.

Thomas Brereton, the Master of the Betty

The next on our list was to find out more about the master of the Betty, Thomas Brereton.

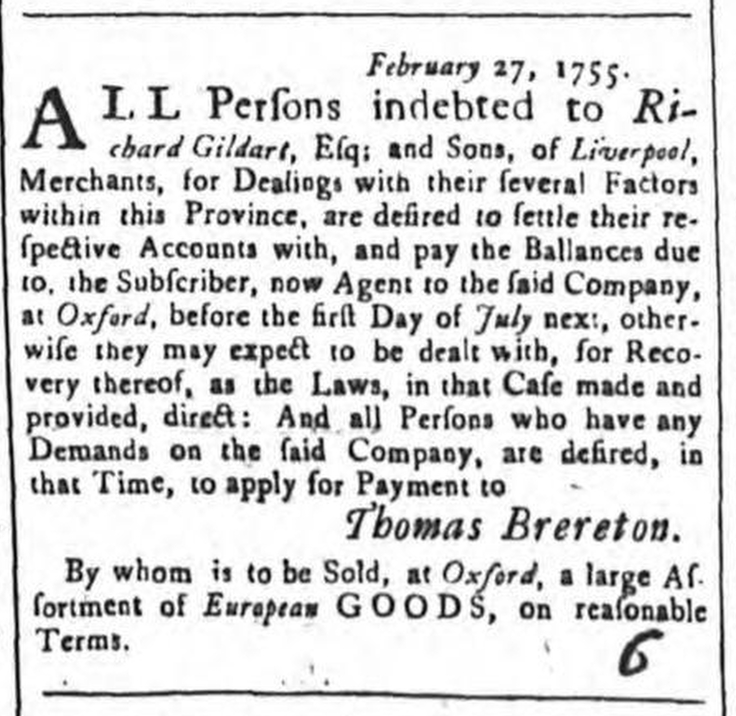

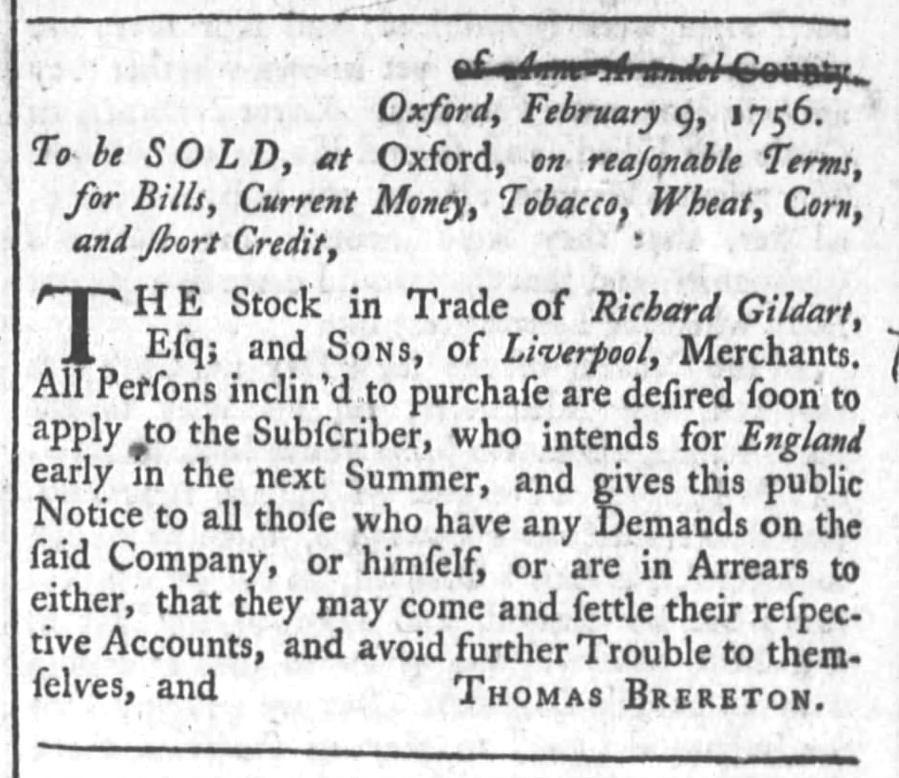

Thomas Brereton #1. When Joseph Manesty sought out alternative employment for Newton, he managed to secure the tide surveyor position for him under the patronage of one Thomas Salusbury. Salusbury had previously changed his name from Thomas Brereton. He was a former mayor of Liverpool 1733-34 and an active Liverpool MP (1724-29, 1734-1756) who stood alongside Richard Gildart. We therefore had Thomas Brereton and Richard Gildart and a Liverpool connection. There was a problem though. Brereton had changed his name to Salusbury in 1748 by deed poll when he inherited a title through marriage, and the Newton boarding was in 1761. We obviously had the wrong man.

Thomas Brereton #2. We then came across another Brereton in the Biographical Annals of Franklin County Pennsylvania, Vol. 1, 1905. Thomas Brereton, 1720-1787, a mariner from Dublin.

Thomas Brereton (born in Dublin, Ireland, May 31, 1720—died at Fells Point, Baltimore, Nov.15, 1787). From his correspondence, which has been preserved, it is learned that he was in the service of Gildart & Co., merchants of Liverpool, England, as captain of one of their ships, in 1752. He was the agent, or factor, of this firm at Oxford on the Choptank river, Eastern shore of Maryland,1754-55, and perhaps later. He returned to Liverpool prior to 1761, and in that year sailed in command of the privateer “Betty,” owned by John Walker of the firm Gildart & Co. The “Betty” was a ship of 350 tons burthen, “manned by forty seaman, and carried twelve six and nine-pound guns, besides swivel guns.”

* Biographical Annals of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, Vol. 1, 1905, p.318

We couldn’t have hoped for a better result, to find a complete biography of the master of the Betty, Thomas Brereton; detailed information about his employer, Gildart & Co; and the owner of the Betty, Liverpool based merchant, John Walker, and, to discover that the Betty was a privateer! This find proved to be a real turning point in our research.

* The author of the Biographical Annals of Franklin County, George O. Seilhamer lived in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and was active within the Kittochtinny Historical Society there. Thomas Brereton’s grandson, Thomas John Brereton (1858-1929), was also a member, which is how we think the family papers came to light. We contacted the Society, which still exists today, but unfortunately it appears that the family papers stayed within the Brereton family, who we haven’t been able to trace.

Was there any evidence of Brereton in Oxford, Maryland?

Thomas Brereton, 1720-1787, an Irishman originally from Dublin, aged 41 (Newton was 36) when the Betty arrived in Liverpool and both men met. The biography extract says that he worked for Gildart & Co at Oxford, on the Choptank River, Maryland, in the American Colonies. We found two newspaper advertisements which confirm this – for years 1755 & 56.

It’s interesting to note the range of acceptable currency noted in the second clipping: ‘Bills [of Exchange], Current Money, Tobacco, Wheat, Corn, and Short Credit’; and the demand to settle outstanding accounts in the first clipping.

Who were Gildart & Sons of Liverpool?

The biography reference to the firm of ‘Gildart & Co’ is expanded upon in the newspapers advertisements as ‘Richard Gildart, Esq; and Sons, of Liverpool‘.

Richard Gildart,1671-1770, was Mayor of Liverpool three times in 1714, 1731 & 1736, and represented the town in Parliament from 1734-54*. He was a prominent slave trader, tobacco, and rock salt merchant, and the son-in-law of Sir Thomas Johnson – a leading town figure and one of the architects behind the town’s early success. Both men had significant ties to the Virginian tobacco trade.

‘The Gildarts concentrated their tobacco-buying on the York and Rappahannock [rivers] and competed with Cunliffe for a share of the Maryland’s Eastern Shore bright oronoco tobacco. The two firms were also Liverpool’s two largest suppliers of slaves to the region, each firm transporting nearly 2,000 Africans to Virginia and Maryland between 1732 and 1767.’

Lorena S. Walsh, ‘Liverpool’s Slave Trade to the Colonial Chesapeake’ – featured in Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, 2007

* Liverpool had two Members of Parliament, the other MP who ran alongside Gildart from 1734-1756 was non other than Thomas Brereton (later Thomas Salusbury) – our first Brereton candidate. He was also an MP from 1724-1729, and mayor in 1733, and held the post of Commissioner for victualling the navy 1729-47.

The biography also mentioned that Brereton was captain of one of Gildart’s ships in 1752 but we were unable to find any record of it.

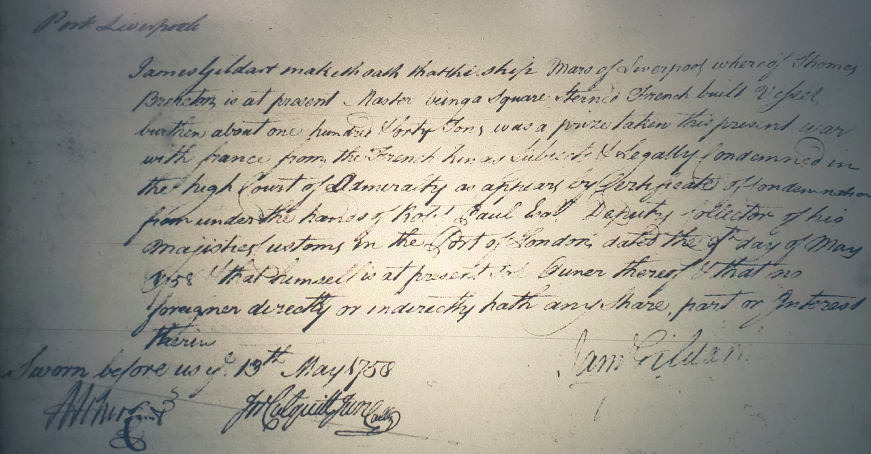

We did however come across a much later dated vessel. Brereton was captain of the Mars in 1758, which belonged to Richard Gildart’s son, James. The Mars departed Liverpool on the 20 July, 1758, bound for Virginia.

The ship Mars – we also discovered the Mars in the Mersey Marine Museum Plantation Registers, dated 13 May, 1758, which names both Thomas Brereton as master and James Gildart as sole owner. This is the ship’s registration before she sailed in the newspaper clipping above. Interestingly, she was French built, 140 tons burthen, and was ‘a prize taken this present war with France from the French King’s Subjects’. Mars was formally named Turbot, and was captured by William Hutchinson, a privateer, and master of the ship, Liverpool.

Who owned the Betty?

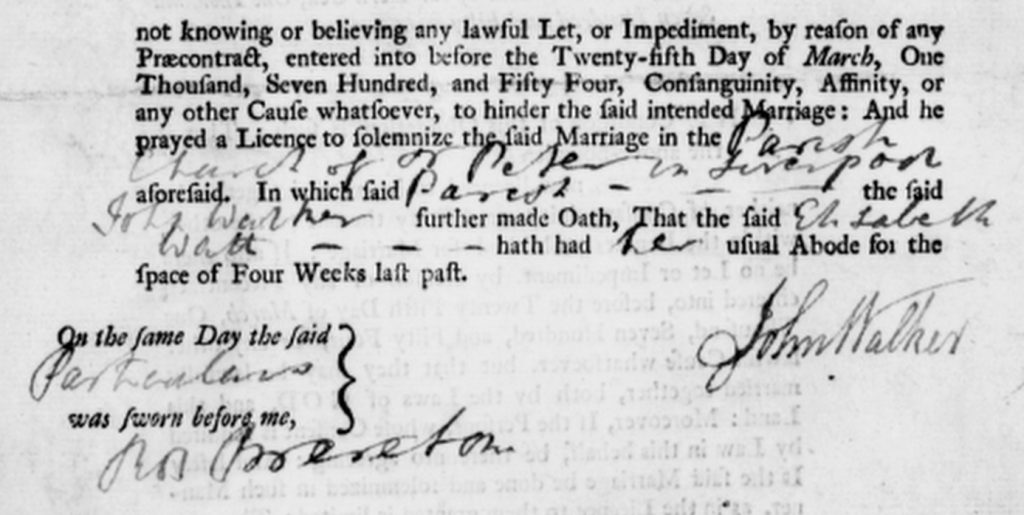

John Walker was named in the Biography entry as the owner of the Betty. He was listed as a merchant of the town on his marriage license.

John Walker (d.1769) married Elizabeth Watt on 20 October, 1759 – ‘in the Parish Church of St Peter in Liverpool’. Witnessed by Thomas Brereton. Our first Thomas Brereton candidate had changed his name by deed poll in 1748, so, legally, he was Thomas Salusbury by the time of the wedding. It had to be our Irish-born mariner from the Chesapeake.

Elizabeth Watt, Walker’s wife, was probably the Betty that the ship was named after. She was ‘the sister of Richard Watt, of Kingston, Jamaica, a young lady of genteel fortune.’* Tony Tibbles also adds that ‘this ‘genteel fortune’ was presumably the result of her brother’s generosity rather than any inheritance.’

*‘My Interest Be Your Guide’: Richard Watt (1724–1796), Merchant of Liverpool and Kingston, Jamaica, Tibbles, Tony

Walker was later to go into business with Richard Watt but after 1761 our year of interest.

Did the Betty have any other owners besides John Walker? A higher percentage of Liverpool ships were owned by a consortium (to spread the risk and cost of a voyage) than were owned privately. Was this also the case with Betty?

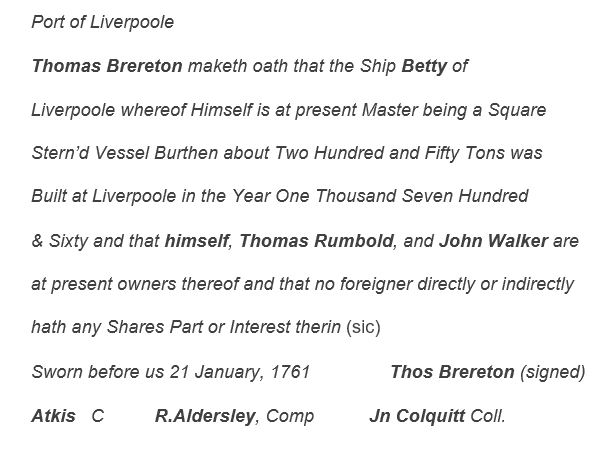

One way to check this is through the Liverpool Plantation Registers held at the Merseyside Maritime Museum.

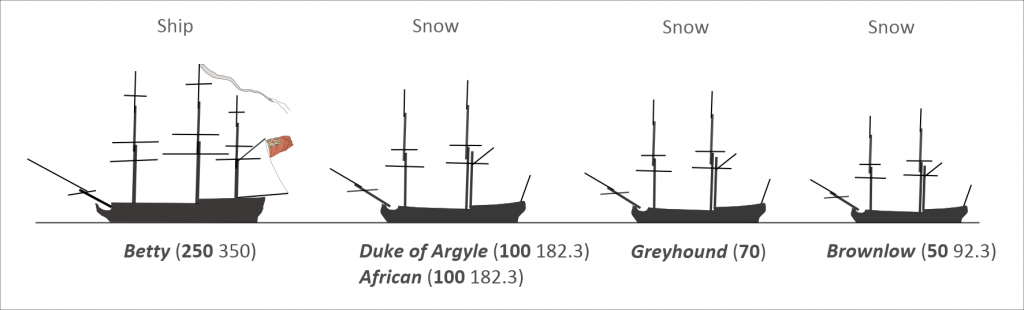

The Plantation Register entry for the ship, Betty – dated 21 January, 1761, confirms John Walker as owner. But it also confirms two other co-owners: Thomas Brereton (her master), and Thomas Rumbold. It further adds that the Betty was built in Liverpool in 1760, and was ‘a Square Stern’d Vessel, Burthen about Two Hundred and Fifty Tons.’ This differs from the Brereton biography account of 350 tons. The reason for the discrepancy was that owners before 1786 registered a ship’s tonnage at approximately two-thirds of her actual tonnage (or measured tonnage).

‘This registered tonnage was less than a vessel’s “measured tonnage.” The latter was the basis for building, buying, and selling vessels… Registered tonnage was then estimated at roughly two thirds of measured tonnage… This practice was encouraged by ships’ captains and ship owners who wanted to minimise lighthouse and port duties that were based on tonnages.’

French, Christopher J. “Eighteenth-Century Shipping Tonnage Measurements.” The Journal of Economic History, vol. 33, no. 2, 1973, pp. 434–43.

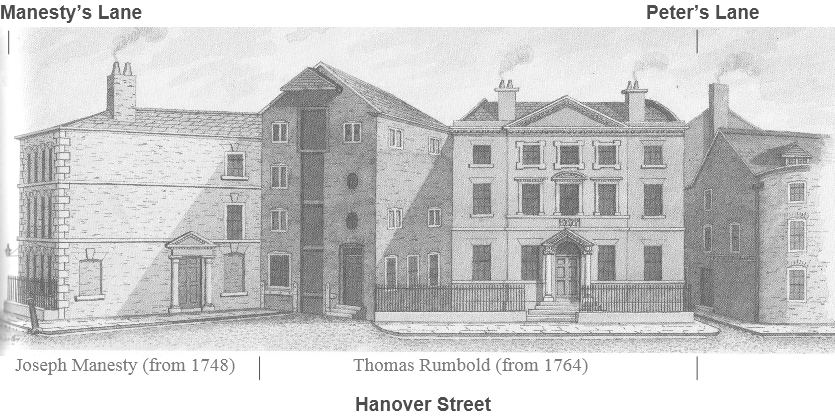

Thomas Rumbold c.1724-1791 was a merchant of Liverpool and actively involved in the transatlantic slave trade. A search of his name returns 74 slave ship voyages in the Slave Voyages database, totalling 24,417 captives embarked.

Rumbold leased this property on Hanover Street in 1764. John Newton’s patron and employer, Joseph Manesty, lived next door. John Walker leased a warehouse opposite the house (not in view) in 1763.

The ship, Betty, a privateer?

The Betty was built in Liverpool in 1760 and registered 21 January, 1761 by her owners: John Walker, Thomas Brereton and Thomas Rumbold.

She is described as a privateer* in the Biographical Annals papers (quoted again, below). But no record could be found of her in the Prize Court: Registers of Declarations for Letters of Marque, held at the National Archives. There are eight entries listed for Thomas Rumbold – for ships: Esther, Rainbow, Rumbold, Tryton (sic) and four listings for the Anson. And neither John Walker or Thomas Brereton’s name appears in any of the records. John Walker is, however, listed as a part owner of the Rumbold in the Slave Trade database.

* Letter of marque were Government issued licenses that enabled private citizens, privateers, to attack or capture an enemy vessel. Records of letter of marque vessels are held at the National Archives.

[T]he privateer “Betty, ‘ owned by John Walker of the firm Gildart & Co. The “Betty” was a ship of 350 tons burthen, “manned by forty seaman, and carried twelve six and nine-pound guns, besides swivel guns.’

Biographical Annals of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, Vol. 1, 1905, p.318

If the Betty was not a letter of marque “privateer” (assuming the record was not lost) what was she then? Part of the answer is revealed in the next section.

The Chesapeake Convoy

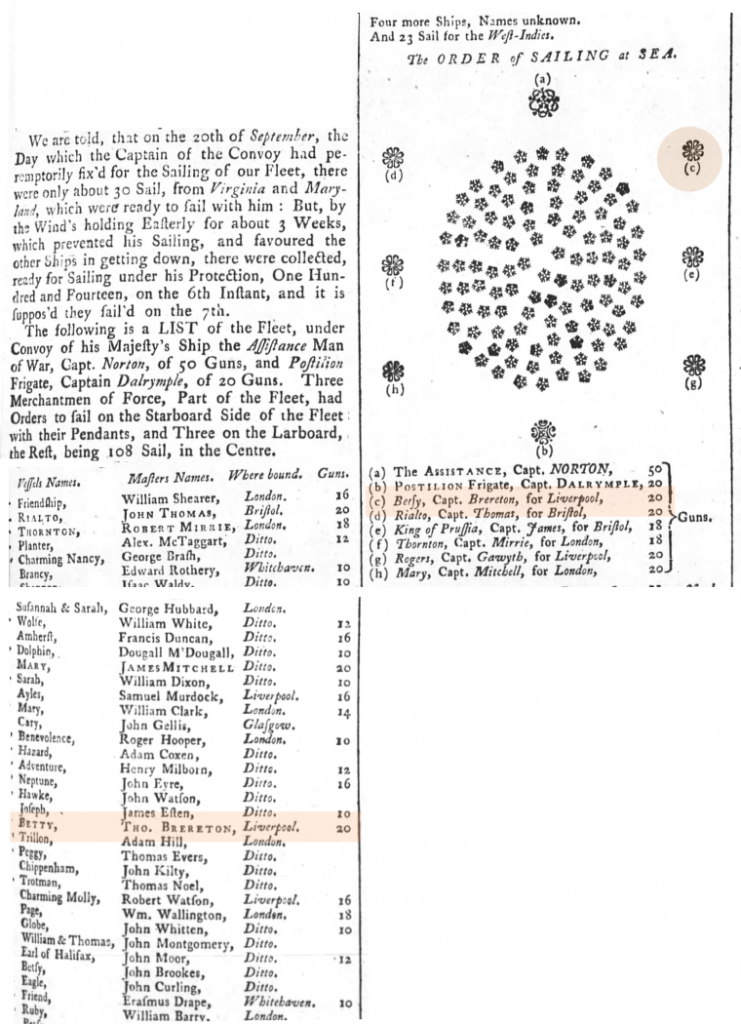

There’s a report in The Maryland Gazette that details the final preparations that the Betty undertook for her return voyage from Virginia to Liverpool. This is the same voyage that Newton later boarded, as detailed in the 29 November, 1761, C&NM docket. She was part of a convoy of ships that assembled in Chesapeake Bay between Virginia and Maryland, late September, 1761.

A fleet of 30 ships had planned to leave the Bay on 20 September but due to the ‘Wind’s holding Easterly for about 3 Weeks’ it delayed the voyage, allowing more shipping to join while they waited for more favourable sailing conditions. By 6 October, the convoy had grown in size to 114 ships. It had planned to leave the Bay the following day, on the 7 October, 1761.

The Betty, a ship of 20 guns, played a defensive role in the convoy. She is described as one of ‘Three Merchantmen of Force, Part of the Fleet, [that] had Orders to sail on the Starboard Side of the Fleet with their pendants’. Another three merchantmen of force were positioned on the larboard (or port) side, totalling six. The convoy was headed by ‘his Majesty’s Ship the Alliance Man of War, Capt Norton, of 50 Guns’; and at the rear by ‘Postilion Frigate, Captain Dalrymple, of 20 Guns.’

There is a helpful diagram of the convoy (showing 108 ships in the centre) with Betty positioned on the starboard side. The names of the eight ship captains defending the fleet are capitalised in the list, which is a shortened, cropped extract. ‘BETTY, Tho. Brereton’ appear in the left list; and ‘Betsy, Capt. Brereton‘ in the right. Perhaps it was a mistake by the journalist rushing to get it to print? Or maybe the crew just referred to Betty as Betsy?

The Chesapeake Bay convoys were generally coordinated with the tobacco harvest season and auctions that followed in the Virginia fall. The exceptions were the Gildarts and the Cunliffes who sent two shipments per year.

‘The Liverpool and naval stores traders usually sent out one ship per year carrying European merchandise, which they exchanged for a return cargo of tobacco. (Cunliffe and Gildart with their chains of stores on the Maryland Eastern Shore usually sent two ships each year).‘

Lorena S. Walsh, ‘Liverpool’s Slave Trade to the Colonial Chesapeake’

The seasonal scheduling often proved problematic for African slave ship merchants to mesh into their calendar on the West coast of Africa, which could take several months to complete.

‘[M]ost merchants found it more efficient to employ one set of ships in the slave trade and others in the produce trades. Liverpool tobacco traders dispatched cargoes of European goods during the winter months with the intent that they arrive in the Chesapeake between March and June. If all went well, it took about three months to assemble a return cargo of tobacco.’

Lorena S. Walsh, ‘Liverpool’s Slave Trade to the Colonial Chesapeake’ – featured in Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery, 2007

The Betty was registered 21 January, 1761 and departed Liverpool shortly afterwards, reaching Virginia around the end of June – early July (news of her arrival was reported in the English newspapers, 31 July, 1761). She returned back home 29 November, 1761, the same day that Newton had boarded her, a round trip of about 9-10 months.

The Seven Years’ War had, no doubt, adversely affected shipping in the Mersey, with French privateers disrupting the Atlantic trade. It’s perhaps no surprise that all of Thomas Rumbold’s letter of marque ships were also slave ships, to defend from, or attack, hostile French ships, including French merchant shipping. Convoys provided a much needed and protected trade route. They also stopped the drip-feed of shipping into the Mersey by grouping it all together, a factor that gave Newton ample time for study, reflection, and the opportunity to travel back home in Liverpool.

What type of vessel was the Betty?

The Betty was a 20 gun ‘Merchantmen of Force’, perhaps commissioned by Captain Norton to defend the convoy fleet. She also flew a ‘pendant’ flag (also known as a pennant or pennon) – a long streaming triangular tapering flag flown from the highest point on a ship, from the top of the main mast. It was often seen on man-of-war and armed vessels.

She was also a ship class of vessel with 3 masts. By comparison, the vessels associated with John Newton’s earlier voyages to Africa all belonged to the snow class, with two principal masts and a shorter mizzen mast just behind (aft) of the main, all much smaller vessels.

The Betty compared to John Newton’s earlier ships

Was Betty also a slave ship? There is no record of Betty / Brereton in the Slave Voyages database.

Who was the tobacco supplier in Virginia?

Whilst the Betty was being built in Liverpool, 1760, Thomas Brereton captained another vessel that year, the Gorell – a 200 ton ship. She was built in 1754 by John Gorell and William Pownall at Liverpool. The men were partners in the ship building firm of Gorell & Pownall. They were also her registered owners in 1755.

Also in 1760, Thomas Rumbold and John Walker both entered into a new contract with Richard Corbin (d.1790) of Virginia.

‘[Richard] Corbin was ever ready to begin new ones in hopes of increasing his profits; in 1760 he opened two new accounts, one with the firm of Robert Cary & Co., one with the house of Messrs. Thomas Rumbold & John Walker, the latter on the recommendation of his brother-in-law John Tayloe and another friend’

Scheib, Jeffrey Lynn — editor’s edition, “The Richard Corbin letterbook 1758-1760” (1982).

Richard Corbin was a wealthy land owner, planter, and collection agent for British merchants. He was also a colonial Royalist. In 1762 he became the deputy Receiver General of Virginia responsible for collecting the King’s quit-rents (land tax), a small annual fee paid by a landowner in colonial Virginia.

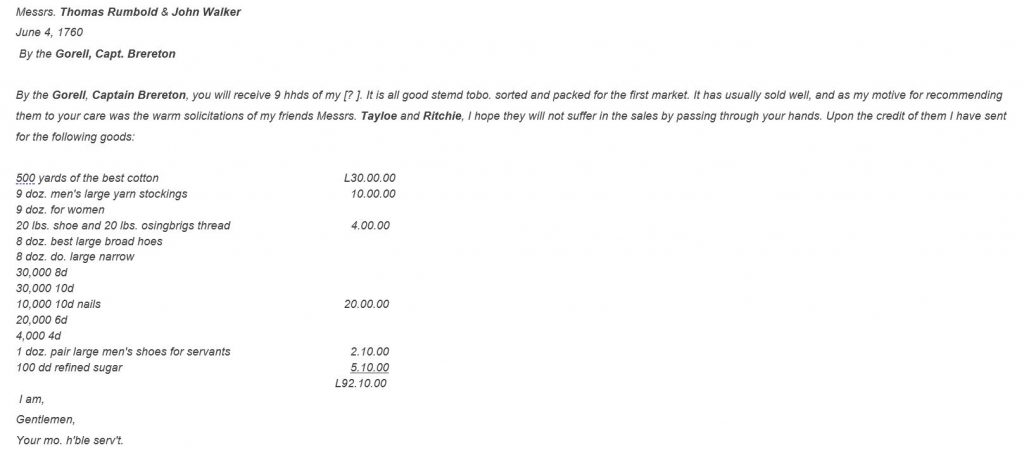

On 4 June, 1760, he wrote a letter, addressed to both Thomas Rumbold and John Walker, relating to Captain Brereton’s return voyage to Liverpool from Virginia on the Gorell. It contains a list of merchandise that Corbin expected in return for the tobacco he supplied.

‘Gorrell, Brereton’ arrived back to Liverpool on 22 September, 1760.

The Corbin manifest, the shopping list of goods he wanted in return for his tobacco, does raise an interesting speculation that the Betty then took them out with her on her maiden voyage to Virginia early the next year*. She was registered in January 1761 and ready to sail once her cargo was stowed.

* We would need to see Richard Corbin’s letter book for 1761 to confirm. This is on a microfilm record in Virginia, and marked for future research.

The trade – Also fascinating is the idea that raw materials such as cotton, sugar and tobacco were landed at Liverpool from the plantations, only to be re-exported back there again once they were refined, or in the case of cotton, turned into fabric from the Manchester mills. Other manufactured items such as yarn, pottery, shoes, clothing, nails, tools, cutlery, dinnerware services, rope, and guns, to name but a few items, were also sent.

Lorena S. Walsh, in her chapter, Liverpool’s Slave Trade to the Colonial Chesapeake: Slavery on the Periphery says this of the Cunliffe and Gildart* chain of ‘stores on the Maryland Eastern Shore… By the 1760s, Liverpool was functioning as something like a Wal-Mart of the eighteenth century’ providing the much needed support that underpinned American progress.

* Brereton’s previous employers.

Quote featured in Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery (Chapter 4), edited by Richardson, Schwarz and Tibbles

The fate of the Betty

Homeward bound – Thomas Brereton made one other voyage on the Betty, returning back to Liverpool from Virginia on 17 November, 1762. The following year, he returned home to Oxford, Maryland, and set himself up as a broker there, and then later at Baltimore, dealing in tobacco, ship sales, insurance, and even selling law books. He was frequently named as an executor in the wills of his neighbours, and in this capacity, he had corresponded with George Washington (before he became president) over the price of tobacco, which had become a family boast. He died at Fells Point, Baltimore on 15 November, 1787.

The new master – After Brereton’s departure, John Walker (or another member of the consortium) found a replacement master for the Betty, and appointed Samuel Kelly. A decision they probably all soon regretted.

Disaster strikes in Ireland – Less than three months after her return, the Betty was loaded with goods, and departed for Virginia again. First, she headed towards Ireland, possibly to pick up more provisions for America, and whilst sailing along the east coast of Ireland disaster struck! The ship found herself stranded ‘on shore near Newry’, off Carlingford Lough, February, 1763.

The extent of the ship’s damage was reported in the Manchester Mercury, 8 March, 1763. ‘It is feared’ that the hull of the Betty is ‘beat out’.

The Dublin Courier, 11 March, 1763, added both tragedy and further mystery surrounding the stranding. ‘The Snow, Betty, of Liverpool, suppos’d to be entirely lost, as some Dead Bodies have been thrown up.’

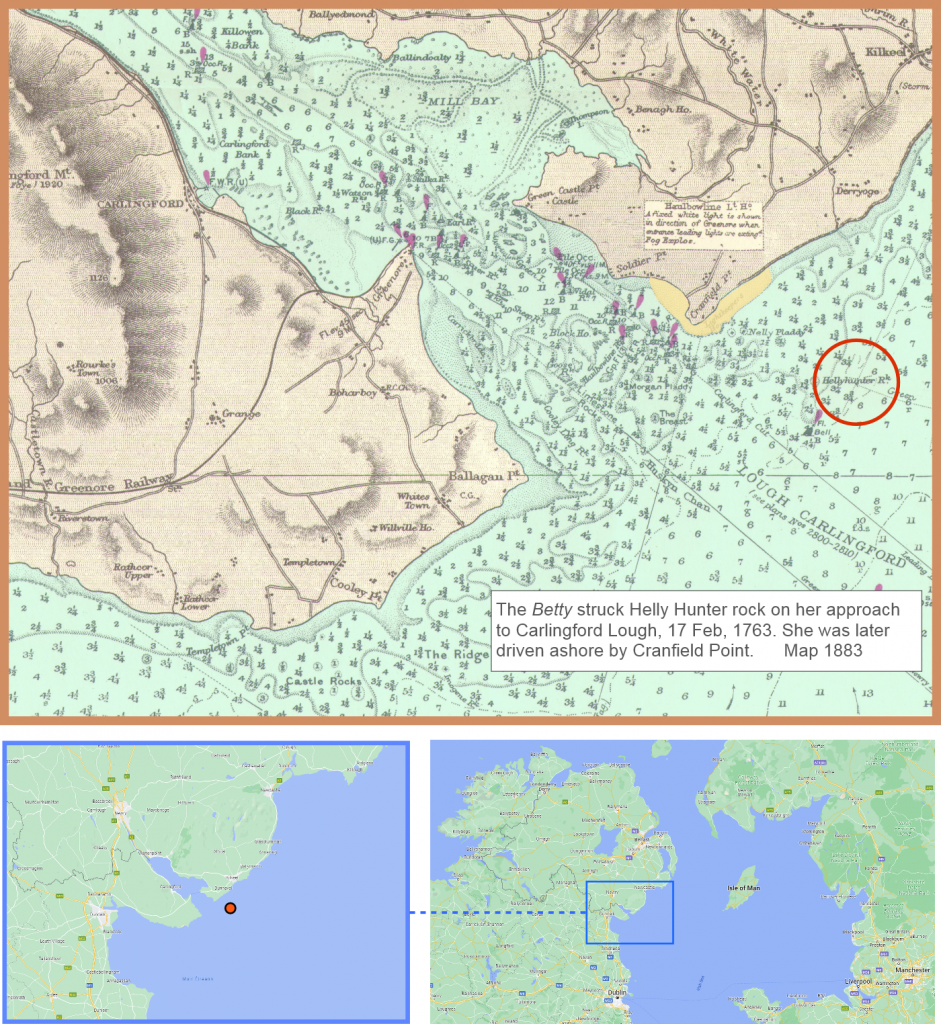

Helly Hunter and the cargo of the Betty – A fuller picture emerged of what happened to the ship in the following article, printed two weeks later, again in The Dublin Courier – Wed 23 Mar – Fri 27 Mar 1763. (FMP)

‘On the 17th of February last, about seven o’clock in the evening, the Betty, of Liverpool, of 350 tuns (sic) burthen, Samuel Kelly, Master, bound for Virginia, with salt, beer, linens of all sorts, almost every article that can be named for wearing apparel and furniture, struck on the rock, called Hilly Hunter [Helly Hunter] about half a league from the northern entrance of the Lough of Carlingford, and of Cranefield [Cranfield] Point.’

We now know the site where Betty floundered. She struck a rock, or more likely a rocky shoal named Helly Hunter, at night, on the approach to Carlingford Lough (which led to Newry), in the Irish Sea (see the map below).

The cargo was similar but more extensive to the original shopping list that Brereton received from Richard Corbin – on his return voyage from Virginia, aboard the Gorell in 1760. Again, it reads as a provisioning stock for a developing and emergent America.

Plunderers and pillagers before dawn – The fate of the ship now hung in the balance the following day, Friday, 18 February, 1763.

‘The master, and whole crew, 26 in number, came on shore that night in boats; the ship was drove upon a sandy beach, on Cranefield (sic) Shore, before morning, and has not yet gone to pieces, tho’ little hopes remain of getting her off. As there are in most countries, near the sea, wretchers in the shape of men, but void of humanity and compassion, so here also there were not wanting a number, who already look’d upon the prey as their own; they beheld with longing, but unrelenting eyes, the most beautiful three masted vessel of her burthen, belonging to England, lying before them, within the grasp of their hands, upon the ebbing of the tide.’

A dozen loaded muskets in defence of the Betty – Local defenders faced off a wrecking crew.

‘This rich, this beautiful object, lay ready to be broken up and pillaged by savage plunderers, when, on the morning of the 18th, it was protected by some humane and resolute inhabitants, in the neighbourhood… Brent Spencer, Esq; of Bellhill… saved all the linens, supposed to be worth 1500l, at least. But the person who most imminently deserves praise upon this occasion is Mr. William Houston, of Lisnacree, the Coast Officer… he came from his own house about a mile distance, early on the morning of the 18th, and personally took post on the shore; and after assembling a guard of honest inhabitants, arm’d above a dozen of them with loaded muskets, and drove off hundreds from the coast and proceeded immediately to salvage of the cargo… night and day, upon the coast, till all was unshipp’d.

Missiles rained down on the ship’s defenders for five or six days.

‘Mr Houston’s courage, his influence and conduct for five or six days, at first defended the ship and cargo, all would inevitably have been lost; for in that time, the most violent assaults were made, even to the knocking down the High Constable, and showering down paving stones upon the guard.‘

Carlingford Lough, Ireland; and the rock shoal, Helly Hunter (ringed red), where the Betty first ran aground.

How much was the Betty and her cargo worth? – The cargo of the Betty was worth twice the value of the ship, according to the account given by the crew. The vessel was

‘350 tuns, a new ship, out upon her third voyage, had cost near 3000l. and mounted 20 guns, during the war; that her cargo, as above, was worth near 6000l.’

The ‘third voyage’ was probably a reference to what would have been her third completed round-trip voyage, had Kelly completed the passage to Virginia, as Brereton has previously captained two separate voyages to and from Virginia. Interestingly, it confirms that the C&NM docket marks the return leg from her maiden voyage to Virginia. John Newton had boarded a brand new ship just over one year earlier in November, 1761.

The salvaged cargo of the Betty – is also reported in the Manchester Mercury, 5 April, 1763. The ship, Nancy, and her master, ‘Kane’, arrived at Liverpool 26 March, 1763 ‘with Wreck’t Goods fr. the Betty’ from Newry, confirming that Mr Houston’s efforts on the shore were eventually successful.

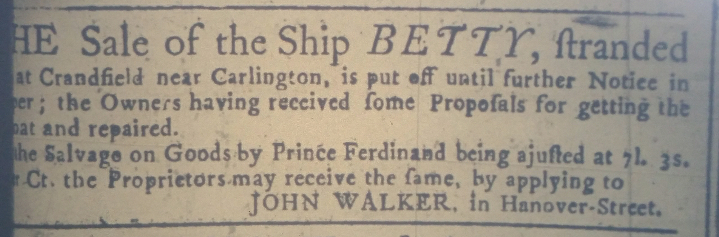

In Liverpool, the owners of the Betty, John Walker & Co, had placed an advertisement in a local newspaper stopping the sale of the stranded Betty. They had received a proposal to refloat the vessel and to have her repaired.

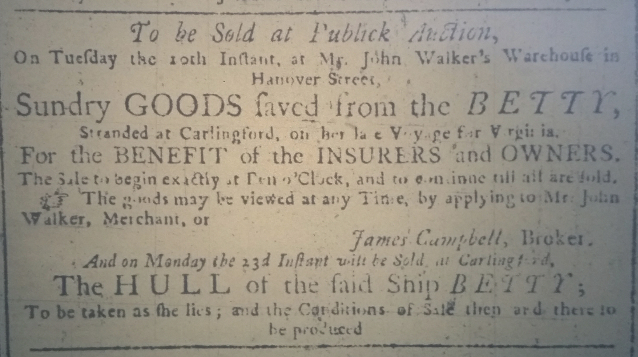

However, it seems not to have been successful. The following week another advertisement was placed by Walker. This time, ‘Sundry Goods saved from the Betty’, are to be sold at John Walker’s warehouse in Hanover Street, Liverpool, 10 May, 1763. There was also confirmation that the hull of the Betty was set to be auctioned off at Carlingford, 23 May, 1763.

What then became of the Betty after the auction? – Unfortunately, we could not trace the vessel after the auction, assuming it went ahead in Carlingford. We also checked the plantation registers in Liverpool to see if we could trace a new registration for the Betty there. It was a popular name, but none of the ships registered after 23 May, 1763, were over two hundred tons burthen. The Betty was 350 tons.

Other possibilities to consider: she was repaired, refloated and sold; no record of the sale has survived: she was broken up on the shore and her timber reused; or, possibly, that she remained a wreck in situ. There are still two unidentified wrecks off Cranfield Point.

The fate of the Betty, at least for now, remains unknown.

Credits:

Thanks to Cowper & Newton Museum for sharing the Betty docket with us and for the opportunity to do the research.

Thanks also to the Liverpool Record Office, Merseyside Maritime Museum, Find My Past, the British Newspaper Archive and the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire.

Notes:

Abbreviations used.

C&NM – Cowper & Newton Museum

LRO – Liverpool Record Office

MMM – Merseyside Maritime Museum

HSLC – Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire

BNA – British Newspaper Archive

FMP – Find my Past

Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser… (abbrev.)

Full newspaper title: Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser and Mercantile Register

The name changed between Mar – Sept 1759 to…

Williamson’s Liverpool Advertiser and Mercantile Chronicle

A Bygone Liverpool history blog which fully explores John Newton’s role as tide surveyor in the Port of Liverpool. John Newton in Liverpool – From slaver to customs official

Part 2 identifies over 30 locations in and around Liverpool that Newton had ties to. John Newton in Liverpool, Part 2. Locations and connections

If you would like to find out more about the history of Liverpool, please visit our site Bygone Liverpool

Other sources:

Biographical Annals of Franklin County, Pennsylvania, pub. 1905. 1978 reprint

Letters to a wife, by the author of Cardiphonia… v.2

Letters written from Leverpoole, Vol 1, 1767, by Samuel Derrick

The Tidesman’s and Preventative Officer’s Pocket-book…, by William Hunter, 1771

The Chesapeake convoy (full article link).

Maryland Gazette, 15 Oct, 1761

Summary of John Newton’s life