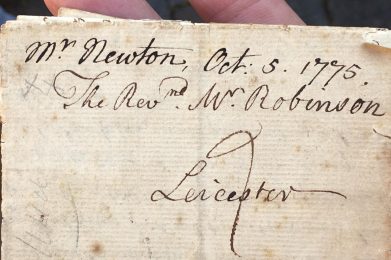

We are delighted to accept a new and exciting donation of a manuscript letter from the private collection of Mike Rendell. The letter was left to him by his great aunt Annie, an eccentric character who lived in an early 20th century commune of goat farmers with a penchant for recreational substances, as Mike describes in his blog on his own website. The letter’s seal and patch of writing underneath is missing, and Mike jokes that his aunt could have sold it or smoked it, for all he knows! Fortunately, a full transcription including the missing text can be found at the John Newton Project’s website.

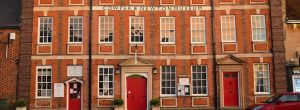

Mike Rendell visited the Museum in September to donate the 245-year-old letter in person. We are incredibly grateful and send heartfelt thanks to Mike, who generously decided to give this valuable item to the Museum for the public benefit, rather than profiting from its sale by allowing it to be ‘snapped up by a wealthy private collector’. The letter has come home, to the house where Cowper & Newton met, talked and wrote the Olney hymns, close to Newton’s former residence and the church where he preached and was finally buried.

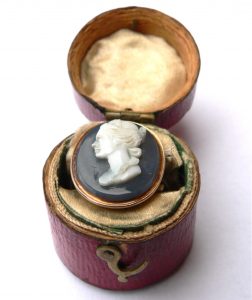

Mike Rendell’s blog contains some very interesting reading about the entire collection of papers and artefacts he inherited, passed down from his ancestor Richard Hall through six generations of his family – The Life of a Georgian Gentleman. The collection has inspired him to write several books about the Georgian era.

This original, handwritten letter is from John Newton to his friend the Reverend Thomas Robinson, a fellow clergyman, who worked at St Martin’s Church in Leicester, which is now Leicester Cathedral. John and Thomas both regarded Leicester as a dark, immoral place, and in fact Thomas once prayed that he would never have to live there. However, Thomas later felt a calling to accept the curacy of St Martin’s – ‘God moves in mysterious ways’!

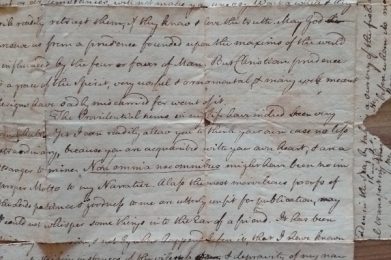

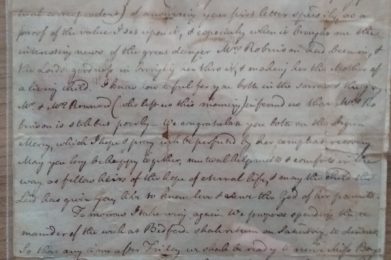

John first apologises for the time he has taken to reply to a letter from Thomas. Thomas had written to John to announce the birth of his baby girl, and tells John that the baby is in good health, but that his wife Mary suffered a difficult birth and was still recovering. Childbirth was a risky business in the 18th Century, with high mortality rates for mother and child alike. An expectant father would naturally worry, hope and pray that his wife and child would survive.

John explains that he was away in London when Thomas’ letter arrived in Olney, and that he had to attend to urgent business on his return, to explain his delay in replying. He wishes Thomas’ wife good health and refers to the grace of God, knowing that his clergyman friend would relate to these religious sentiments.

John is setting off again for Bedford the next day, and is catching the opportunity to write in between his trips. He returns to Olney after a few days and hopes Miss Boys, Mary’s sister will be able to visit him the following weekend on her way to Cambridge, showing a family friendship.

The letter shows deep affection between the two men. John writes at length and with true empathy, to support and defend Thomas from some recent criticism he has suffered. He congratulates Thomas on his virtues such as self-awareness, prudence and pragmatism. He describes his own failings and lifelong guilt for his former involvement in the slave trade.

The friends’ faith pervades every aspect of the letter, even down to John’s wishes that Thomas’ new daughter will grow up to be a good Christian.

Further Reading:

‘Who’s who? Thomas Robinson’ The John Newton Project website

All transcribed letters from Rev John Newton to Rev Thomas Robinson from the John Newton website

Thomas Robinson: Evangelical Clergyman in Leicester, 1774-1813 by Gerald T. Rimmington.

18th century letter writing:

Cowper’s Letter Cabinet – Nicola Durbridge