This article begins by closely examining the pair of Mrs Unwin’s spectacles held in the museum’s collection – their frame, lenses and case. For each of these components Nicola Durbridge outlines a history of its development up to the late eighteenth century, before moving on to consider the different ways in which Cowper and Mary Unwin used their spectacles. She concludes with an account of Cowper’s own eye problems, and the remedies he used to treat them from early childhood onwards

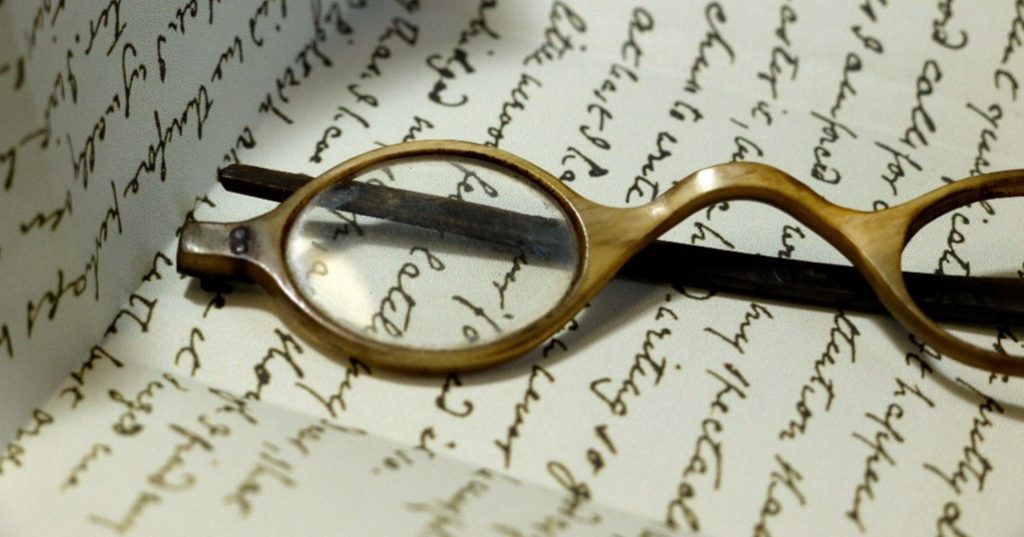

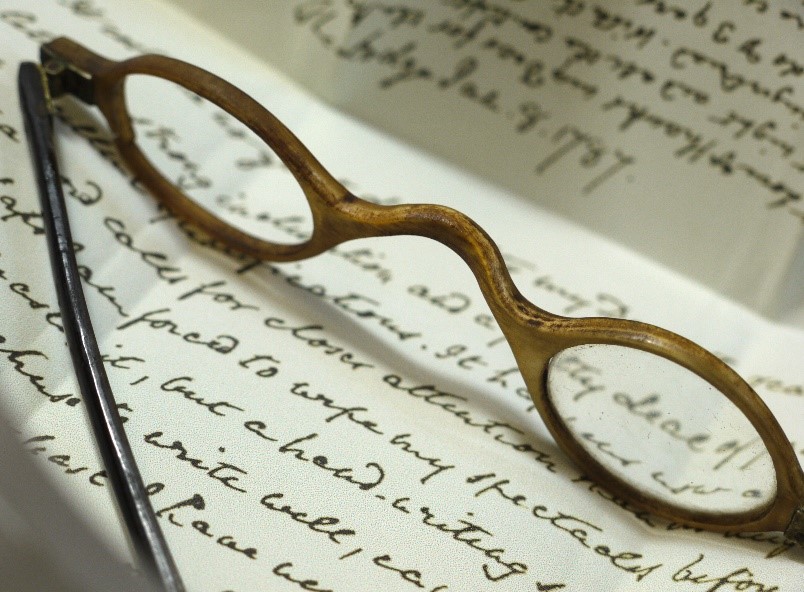

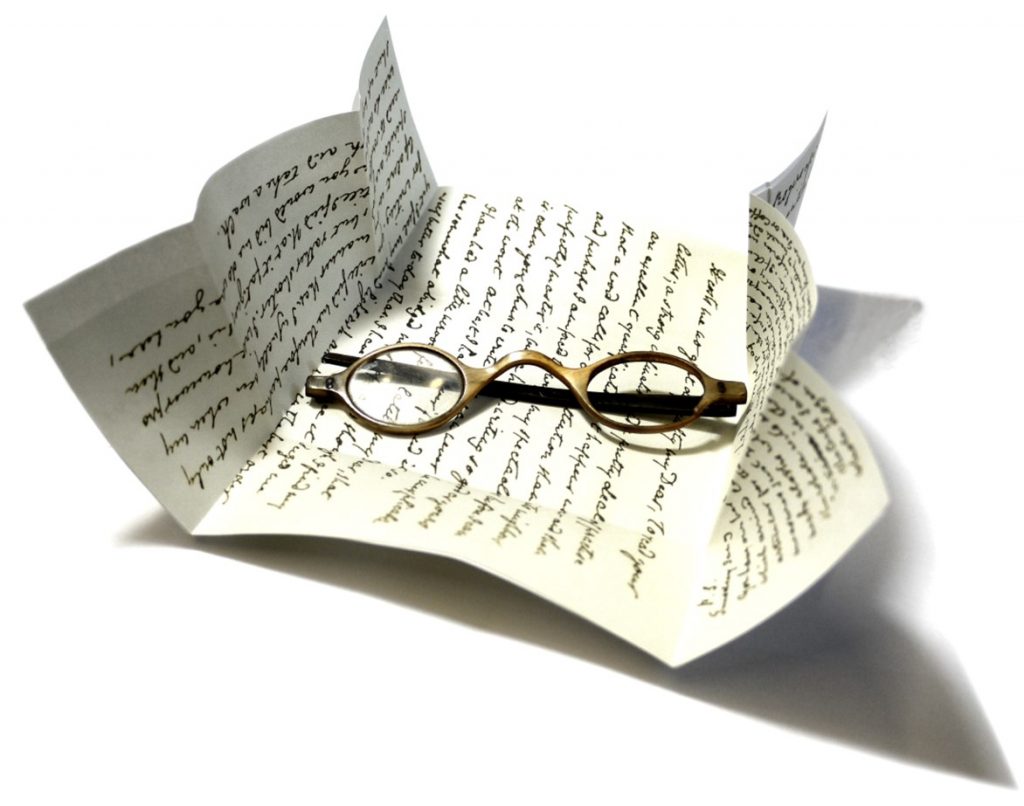

We focus here on a pair of spectacles that belonged to Mary Unwin, Cowper’s longstanding companion, with whom he once lodged and later shared homes. They lived together at both Olney and Weston Underwood.

We focus here on a pair of spectacles that belonged to Mary Unwin, Cowper’s longstanding companion, with whom he once lodged and later shared homes. They lived together at both Olney and Weston Underwood.

Cowper and Mary both needed spectacles to improve their eyesight. In his letters Cowper often refers to his weak eyes and rather poor vision, along with references to how he managed these problems. So he mentions his glasses and their maintenance as well as some other, more rarefied-sounding, remedies for eye troubles. We’ll be drawing on these references in what follows.

The museum doesn’t own any spectacles that belonged to Cowper, so we can’t be as precise about the kind he wore, nor their strength, as we can about Mrs Unwin’s. But her glasses make a good starting point for investigating the state of spectacle art in the mid- to late eighteenth century. And we do so, for the most part, by looking, through Cowper’s own, spectacled eyes at the text of some of his letters.

Mrs Unwin’s spectacles: the frames

Let’s begin by looking at the frames of Mrs Unwin’s glasses. These are made of horn and have silver hinges at the joints.

Horn was a common framing material up to the end of the eighteenth century, and is still in use today. The most common other materials used in the first days of spectacle making – so from the thirteenth century on – were wood, bone and leather. Over time almost every conceivable material has been tried: whalebone (baleen), ivory, tortoiseshell, rubber and many kinds of metal. Very few examples of the earliest glasses survive, though they are illustrated in portraits, providing us with good visual evidence of their use and their appearance.

Horn is a difficult material to work as it tends to fragment – to de-laminate. Also it is not easily shaped into curves – clearly a disadvantage if you are seeking, as here, to frame a circular lens. It was popular though, and happened to be rather fashionable at the end of the eighteenth century when our pair was made. The appeal of horn as a framing material is not surprising as it often has a very attractive ‘look’. Mrs Unwin’s frame, for example, is a rich honey colour and gently patterned. Horn also has a good ‘feel’: it is smooth and comfortably light-weight.

There is another fashionable element to Mrs Unwin’s glasses: they are oval. Until the end of the eighteenth century lenses, and thus frames, were almost always round. This shape persisted perhaps because a round is so geometrically satisfying and is readily understood in many cultures as a ‘right’ shape. It persisted too perhaps because it is a practical shape for eye-glasses – a circle is relatively easy to frame and it matches the shape of an eyeball. So form meets function here and, as such, circular lenses conform to a basic principle of good design.

Mrs Unwin’s frames have a further distinctive eighteenth-century feature: they don’t just surround the lenses, they have short side arms, designed to grip the wearer’s temples (these are called ‘temple spectacles’) and so stay in position.

Until this invention – usually credited to Englishman Edward Scarlett in around 1730 – spectacles were mostly of ‘rivet design’. These were shaped to perch on a wearer’s nose by linking the two lenses with an inverted ‘V’ which could sit astride the bridge. This linkage was made of the lens-framing material and was riveted at the top of the ‘V’. But spectacles of this sort still usually had to have a little hand support if they were not to slip forward.

Apart from rivet spectacles there had been a number of design ideas for keeping spectacles in place – none of them very successful. For example, in the seventeenth century glasses were built with a rigid, arch-shaped nose bridge linking the two lenses but these also needed to be hand-held or they fell off. Another solution for keeping spectacles in position was to attach string or ribbons to the lenses and loop them over the ears. (It’s a design that features in many early portraits of eminent Chinese philosophers and courtiers.) So eighteenth-century ‘temple spectacles’, with their short arms that did not interfere with wigs yet were long and firm enough not to need ear loops, were quite a breakthrough in spectacle design.

Lenses: historical background

Let’s consider now the all-important lenses. These are made of glass. As you can perhaps see, the frame round one lens has cracked and the glass it held is missing.

The early history of eyeglass technology is rather vague, however it is generally agreed that the earliest lenses were not made of glass but of natural stone. These became the ‘reading stones’ used by long-sighted monks to help them in their all-important reading and writing work in the scriptorium. The first stones were probably spherical lumps of natural crystal – transparent quartz and beryl; and it was perhaps just by chance that it was discovered that if you looked through a convex-shaped piece of rock crystal objects appeared magnified. Self-evidently this helped people to see these objects more easily and in more detail, and was particularly useful if you suffered from long sight. It was a small step from this to discovering that the smaller the spherical radius of a stone, the stronger the magnification; and, from there, that by grinding convex crystal to different angles those with long sight could be helped to see even more efficiently.

Lens makers

In the western world, the expertise of thirteenth-century Venetian glass makers ruled the day when it came to the first glass lens-making. These craftsmen were able to produce finely ground and polished convex glass discs – small magnifying lenses – that could be framed and held in position in front of the eyes or lodged on the nose with a hinge. There are many Italian paintings from 1352 on depicting monks and saints wearing spectacles – perhaps as a symbol of their wisdom and out of respect.

The Venetians, and their Florentine near neighbours, both of whom had long experience with glass, went on to corner the European eye-glass market and continued to do so well into the seventeenth century. Their control over this field included a fifteenth-century development – the making of concave lenses as well as convex ones – to help the near-sighted see further.

The Germans on the other hand dominated the frame making part of the spectacle trade. Nuremberg craftsmen for instance (famous makers of tin toys and ‘cheap goods’) produced a ubiquitous, all-wire frame that allowed wearable eye-glasses to be bought for pennies. So between them Italy and Germany controlled the early manufacture and sale of spectacles in the West. But we’re talking quantity not quality perhaps, for basic glasses of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries were really cheap and bought by trial and error: they were mass-produced, touted around by peddlers by the sackload and sold for a few small coins. For instance, a pair of leather spectacles – they looked rather heavy, like goggles – might be bought for one penny, and ‘gilt horn’ glasses for nine pence.

But this cheapness is interesting, as it means straightforward spectacles were not just goods for the rich and powerful, nor were they designed to make an expensive fashion statement; instead they were affordable by ‘ordinary’ artisans and other working folk. We know for example (from shop records and artworks) that masons, clockmakers, tailors, shoemakers, hermits, and schoolmasters amongst many others, bought and wore spectacles. And – just to give us a better sense of what ‘affordable’ might have meant in the fifteenth century – records reveal that Italian masons of that century could earn about 17 ‘soldi’ a day, while a cheap pair of spectacles cost around 2 soldi. So – they were hardly a luxury item that ate deeply into a daily wage. (A pricier pair might range in price from 6 to18 soldi.)

Even in the eighteenth century, a cheap pair of imported German metal spectacles cost a mere one penny in England. Meanwhile London-made spectacles of this period were relatively expensive as they belonged to the growing trade (from the sixteenth century on) in technically more sophisticated lenses and frames. (English spectacles might cost as much as much as three shillings in 1800.) So it’s clear that in many respects a pair of spectacles was a ‘better buy’ then than they are today. But what were they like? Were they any good?

Rules, regulations and specifications

There were controls over spectacle-making from the earliest days. For example, by 1300 the Guild of Crystal Workers in Venice had regulations governing the making of ‘discs for eyes’.

England joined the business much later on. But in London too, the Worshipful Company of Spectacle Makers (with the comforting motto on their coat of arms ‘A blessing to the Aged’), established in 1629, introduced further regulations governing spectacle making (details sadly lost in the Great Fire of 1666.) English spectacle makers were often of a scientific bent: makers of scientific instruments and other precision tools with some element of glass along with spectacles. For example, an eighteenth-century London maker, called Ayscough, (a significant figure in the development of spectacle design – he invented double-hinged sides on spectacle frames) advertised his reading and other eye-glasses along with those for his barometers, telescopes and mathematical instruments.

A quasi-scientific approach to lens manufacture too is evident from early on: lenses were already ground to age-graded specifications and marketed by such gradations. So, by the mid-fifteenth century, Florentine records show that spectacle makers produced glasses at varying strengths, designed to match the age of their purchaser and wearer. The strength of spectacle lenses was graded in five-year leaps to match the stages by which eyesight was agreed to decline with age. And so, starting at age 30, lenses in spectacles were ground with progressively stronger magnification to help with increasing long-sightedness. Glasses were thus bought by age: pairs for 35-year-olds, 40-year-olds and so on.

As we shall see later, it is possible that Cowper was referring to this system when he ordered a pair of new spectacles in the 1780s.

Mrs Unwin’s spectacles: the lenses

But back to Mrs. Unwin’s glasses again. Out of curiosity, we investigated the strength of the remaining lens in her spectacles and it turns out that she was slightly longsighted, a common condition with aging. The surviving lens has a magnification of 2.5, which means her vision was not so greatly impaired and might not have been much of a problem to her except when she was doing close work, or was in poor light and tired. These glasses would have helped her with reading obviously – those religious texts so important to her perhaps – and with the finer handicrafts she liked to pursue.

We know, from Cowper’s descriptions of evenings spent together in the parlour at Orchard Side, that she was a much-practised needlewoman, knitter and knotter. The handling of finely spun cotton and silk and the other threads involved in this work would have required keen eyesight, and would have been particularly demanding on an eighteenth-century winter evening in a room only dimly lit by candles.

There is a nice description of a bespectacled Mrs. Unwin, knitting away ‘on the FINEST needles’ with Cowper seated nearby, written by Harriot (Lady Hesketh, Cowper’s cousin) in a letter to her sister Theadora. It gives us a vivid picture of the scene:

‘Our friends delight in a large table and a large chair. There are two of the latter comforts in my parlour. I am sorry to say, that he and I always spread ourselves out on them, leaving poor Mrs. Unwin to find all the comfort she can in a small one, half as high again as ours, and considerably harder than marble…Her constant employment is knitting stockings, which she does with the finest needles I ever saw; and very nice they are – the stockings I mean. Our cousin has not for many years worn any other than those of her manufacture. She knits silk, cotton and worsted. She knits sitting on one side of the table in her spectacles, and he on the other reading to her (when he is not employed in writing) in HIS.’

There’s perhaps a rather ‘othering’ tone to Harriot’s depiction of this scene: Mrs Unwin relegated to a hard, low chair and forever knitting, while Cowper and Lady Hesketh sit apart and, one senses, engaged in more distinguished pursuits as well as in greater comfort. But it’s a comment that comes perhaps with the benefit of hindsight; for Harriot, in letters written when Mrs Unwin was frail and ill-tempered and close to dying, reveals quite a dislike and some disdain for Cowper’s companion. Earlier on she claimed to admire her but came, it seems, to lose patience with the old lady in her illness and declining years, and was inclined to mock her.

We see this in letters to cousin Johnny Johnson in the 1790s for example, when she was looking after both Cowper and Mrs. Unwin and probably rather worn down by the task. Harriot could not resist sniping away at Mrs. Unwin’s behaviour and regularly called her ‘the enchantress’. She let off further steam by implying that Mrs Unwin had become malevolent and manipulative – rather than perhaps just ill, old and a bit selfish. When it came to ‘our dearest Cousin’ (William), it seems Harriot felt a little proprietorial, and rather jealous of his dependency on others – apart from family. (Cowper’s friend Hayley was another she came to resent.)

Nevertheless she gave us a good account of them both wearing their spectacles of an evening. And Cowper too had occasion to mention Mrs. Unwin’s knitting in poor winter light and, so we might infer, wearing her spectacles. In 1788, for example, he detailed how they spent early mornings in winter:

‘I have told you before, I believe, that the half hour before breakfast is my only letter-writing opportunity. In summer I rise rather early, and consequently at that season can find more time for scribbling than at present. If I enter my study now before nine, I find it all at sixes and sevens; for servants will take, in part at least, the liberty claimed by their masters. That you may not suppose us all sluggards alike…Mrs. Unwin, who, because the days are too short for the important concerns of knitting stockings and mending them, rises generally by candle-light…’

Finally, and before we consider Cowper’s problems with his eyesight, we should take a look at the case in which Mrs Unwin kept her glasses.

Mrs Unwin’s spectacles: the case

Mrs. Unwin kept her spectacles in a black, papier-mâché case. It is a narrow oblong with rounded ends. The case is a tight fit for the frames, and it seems quite likely that the squeezing and pushing required to get the spectacles snugly into it caused the damage we’ve already noted.

But the case is in good condition: papier-mâché is quite a tough, durable material provided it is kept dry, despite its squishy, fibrous origins. The ‘mash’ is made from paper pulp mixed with paste and worked to a putty-like consistency, then moulded into shape. Alternatively, pasted layers of paper may be moulded or freely formed. Papier-mâché is a cheap, versatile substance that has been used over time to make many personal or household objects. Though plain in origin, it is easy to embellish with moulded or applied decoration.

Since it is easy to work, papier-mâché is often applied as an ornament – for example as a three-dimensional decoration that is merely glued to an otherwise plain picture frame. Or it might be formed into lightweight household items – trays, small portable writing slopes, tiny shelves or pen and ink stands, for instance. It’s a cheap material but it can be finely finished to suggest a costly product. Many a treasured personal accessory, such as a snuff-box, scent bottle or needle-case, has been made from decorated mashed paper.

The kind of surface embellishment found on papier-mâché ranges widely. For example, the material may be painted, gilded, varnished, lacquered or carved. Alternatively it may simply have raised, moulded decoration – as with Mrs Unwin’s spectacle case. Hers is embellished with a pattern of little sprigs – stylised roses and leaves – set within a suggestion of scrolling plant stems. It has been painted black, but the plain, brown, fibrous material, the mash, from which the case has been made, is visible where the lid slides onto the base.

This is about as much information about Mrs Unwin’s spectacles as we can glean from close examination of them and, from reading Cowper’s and Lady Hesketh’s letters about their usage. However, we do know rather more about Cowper’s vision and his treatment of it from the letters; and it is to these and his eyesight that we now turn.

Cowper’s eyesight

When Cowper was eight years old he was sent to live with a Mrs Disney for eye treatment. She was a renowned oculist and, according to Cowper’s ‘Memoir’ written in about 1767, he spent considerable time in her care:

‘Having very weak eyes and being in danger of losing one of them I continued a year with this family.’

Apparently Cowper had ‘specks’ on his eyes and these impaired his eyesight considerably. He was particularly troubled it seems by his left eye – ‘My larboard eye’ as he called it, many years later, in a letter to John Newton.

We do not know much about these ‘specks’ from a medical perspective – what they were, or how caused. But according to some eighteenth-century eye specialists they might have had something to do with having inflamed eyelids. These, they suggested, could bring about films or specks on the eyes. The problem, it was thought, might impair vision, but not necessarily cause blindness.

Whatever the cause, Cowper seems to have been dogged by eye complaints all his life. And he was inclined to have inflamed eyelids. This is confirmed by a note written by cousin Johnny Johnson in the 1790s when Cowper was in his sixties:

‘Cowper was getting on well with his revision of Homer – 60 or 70 lines a day. His eyes were blood-shot, but he had always suffered from inflammation both of the eyeballs and the lids.’

Remedies used by Cowper

Quite apart from wearing spectacles Cowper had other resources he liked to draw upon for help with his eyes. In particular he was a great believer in ‘Elliot’s ointment’. John Elliot was a physician, practising mid-century, who patented a medicine and course of treatment for eye complaints. The ointment is thought to have had mercuric oxide as its main ingredient. In any event, Cowper swore by it; and here he is, in 1782, in his fifties, asking his friend Joseph Hill for a supply:

‘When it suits you to send me some more of Elliot’s medicines, I shall be obliged to you. My eyes are in general better than I remember them to have been since I first opened them upon this sublunary stage, which is now a little more than half a century ago. Yet I do not think myself safe without those remedies, or when through long keeping they have in part lost their virtue.’

A few years later, in 1786, he reminded Lady Hesketh about his ongoing eye problems and mentioned again his reliance on Elliot’s medicines:

‘My eyes, you know were never strong, and it was in the character of a carpenter that I almost put them out. The strains and exertions of hard labour distended and relaxed the blood vessels to such a degree that an inflammation ensued so painful that for a year I was in continual torment, and had so far lost the sight of one of them that I could distinguish with it nothing but the light, and very faintly that. But a medicine of Elliot’s, which I had never tried before, though two of his medicines I had used for many years, through God’s mercy cured me almost in an instant, and my eyes are for the most part stronger now than they were when you used to see me daily. I shall write … soon for a supply of this medicine, for though I do not often want it, I would never be without it.’

Later that same year we find Cowper asking Joseph Hill for more of ‘Elliot’s ointment and the dark coloured eye-water.’

The eye water is thought to have been a ‘camphorated vitriolic water’, as recommended by Elliot in his Medical Pocket Book, published in 1781.

Cowper recommended the ointment to others too, as we can see from this letter written in 1780 to Mrs Newton. He is concerned about an outbreak of smallpox in Olney:

‘The small pox still rages here and many children die of it…Hannah has yet escaped, though two of Mrs. Clarke’s children have had them, and Nanny has been extremely ill. As soon as she began to recover, it was feared she would lose her sight. Her eyes were terribly inflamed, and the sight of one of them almost covered by a thick film. But a few applications of Elliot’s Ointment and eye water have cured her.’

But Cowper was a very practical man and manifestly interested in self-help remedies – often of a herbal sort – for various maladies. He had one related to eyes. It was a cure for a squint, and we hear of it in a letter to Mrs Unwin’s son William:

‘To dispatch your questions first…Wallnut shells skilfully perforated, and bound over the eyes are esteemed a good remedy for squinting. The pupil naturally seeking its light at the aperture, becomes at length habituated to a just position. But to alleviate your anxiety on this subject, I have heard good judges of beauty declare that they thought a slight distortion of the eye in a pretty face, rather advantageous.’

Kind reassurance here to those lucky enough to be pretty in the first place; but just how slight is a ‘slight distortion’? Would it be better to get the walnuts out just in case?

Cowper’s spectacles

We glean perhaps something about the strength of Cowper’s lenses, and thus the weakness of his eyes, from a few helpful sentences written by Cowper to Lady Hesketh in December 1786. Cowper needed new glasses and it appears that he tried to buy some of an appropriate strength by choosing a particular, age-graded lens. He must, it seems, have named an age he thought matched his needs and asked Lady Hesketh to purchase and send him a new pair of this strength. His own, apparently, had a broken frame. In the following letter we learn that the ordered spectacles had arrived, along with some other treasures:

‘I am desirous to send you a line by this post……that I may acknowledge the receipt of the caravan and its contents. I have examined them one by one. I have opened the snuff-box, looked through the spectacles, studied the lamp, and tasted the gingerbread… As to the spectacles, they are exactly such as I called for, and yet I cannot read through them at all. The fact is I suppose that mine are not so young as I imagined them. When I bought them I asked for the youngest, and these which are now upon my nose were presented to me as such. They suited me exactly then, and they do so still, whereas the new ones rather puzzle my sight rather than assist it, whence I conclude that I was older at that time and still continue to be so, than I have been willing to suppose. In short my dear, unless I could send you my eyes as I sincerely wish I could, I know not how this matter can be managed with any certainty of success. The diameter of the glasses being just the same, I once thought of applying myself to the watchmaker at Olney, thinking it possible he might be able to shift the old ones into the new frame, but it presently occurred to me that he might possibly break both the old ones and the new in the experiment, in which case I should become stone-blind as to all the occupations for which I have occasion for glasses. It seems to me therefore on the whole the wisest course to return them, which I will do by the first safe opportunity.’

But what, in the end, does he decide to do? Two days later Cowper wrote again to Harriot with his solution:

‘…the vulgar adage which says, Second thoughts are best, observes that the third thought generally resolves itself into the first. Thus it has happened to me. My first thought was to effect a transposition of the old glasses into the new frame; my second, that perhaps both the old glasses and the new frame might be broken in the experiment; and my third, nevertheless, to make the trial. Accordingly I walked down to Olney this day, referred the matter to the watchmaker’s consideration, and he has succeeded in the attempt to a wonder. I am at this moment peering through the same medium as usual, but with the advantage of a more ornamental mounting.’

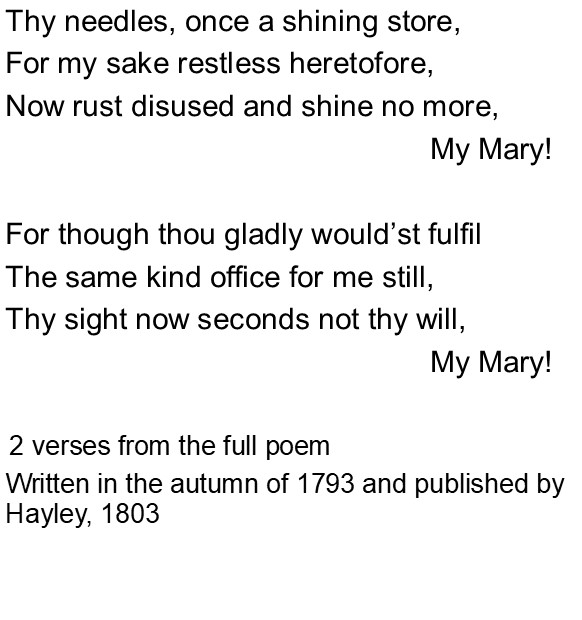

It seems that Cowper was able to struggle on, still able to read with the help of his glasses, almost until his death in 1800. Mary died in 1796, but by 1793 her sight had deteriorated to the point where even her spectacles were of no use, and she could no longer knit or sew.

Further Reading:

Eighteenth century spectacles – Eyewear in the 1700s from the College of Optometrists

What a spectacle! by Sarah Murden on All Things Georgian

Letters of Lady Hesketh to the Rev. John Johnson, concerning their kinsman William Cowper the poet by Hesketh, Harriet Cowper, Lady, 1733-1807; Johnson, Catharine Bodham Donne

My Mary by William Cowper

Memoir Of The Early Life Of William Cowper, Esq. by William Cowper

The Medical Pocket-book: Containing a Short But Plain Account of the Symptoms, Causes, and Methods of Cure, of the Diseases Incident to the Human Body. … Extracted from the Best Authors, and Digested Into Alphabetical Order. The Second Edition, with Additions and Corrections. By John Elliot, M.D.