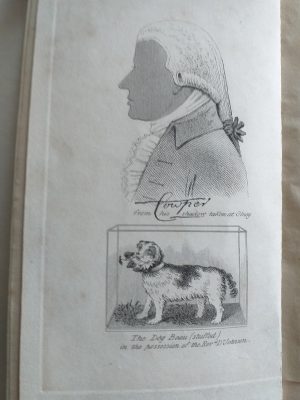

So familiar is the depiction of Cowper in terms of the three male hares that he reared and kept as pets, Puss, Bess and Tiney, that this frontispiece to an early and extensively illustrated book devoted to Cowper’s Olney may well come as something of a surprise. It shows a silhouette of Cowper’s head ‘from his shadow taken at Olney’, with a facsimile of his signature beneath, and below it a stuffed spaniel in a glass case, with a rose held in its mouth.[i] The caption reads ‘The Dog Beau (stuffed)’. Cowper, man and author, is composed with pet, house, and a suggestion of domestic pursuits to create a visual of all you need to remember about Cowper.

Over the remainder of the nineteenth century Beau regularly appeared alongside other motifs that commonly characterised Cowper. G.K Chesterton provides a piece of typically paradoxical evidence for this when he complained that in the English Church Pageant of 1909, in the section devoted to eighteenth-century writers, although Cowper was identifiable by his night-cap, he was accompanied by neither cat nor spaniel.[ii]

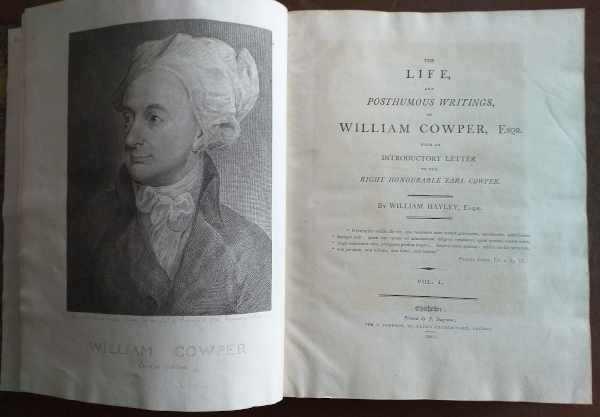

It is surprising that Chesterton did not mention the lack of hares also, given their prominence in depictions of Cowper from William Hayley’s three-volume The Life and Posthumous Writings of William Cowper (1803) onwards. This gives the hares some importance in the table of contents for volume 1 (‘His tame Hares one of his first amusements on his revival [from severe depression])’[iii], commenting further that ‘These interesting animals had not only the honour of being cherished and celebrated by a Poet, but the pencil has also contributed to their renown; and their portraits…may serve as a little embellishment to this Life of their singularly tender and benevolent protector.’[iv]

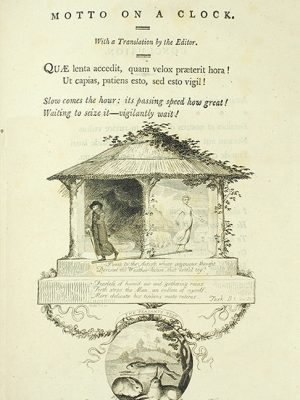

The ‘embellishment’, executed by William Blake as a tail-piece to the last volume, consists of Cowper’s ‘Motto on a Clock’, below which the ‘weather-house’ mentioned in Book 1 of The Task appears, with the muffled-up man representing bad weather with whom Cowper identifies:

‘Fearless of humid and gathering rains

Forth steps the Man, an emblem of myself,

More delicate his tim’rous mate retires.’

Below again is a tiny representation of the view of the cottage called ‘the Peasant’s Nest’ described in The Task, and below that again the three hares variously bounding and couched, clearly adapted from Cowper’s treasured snuff-box, and captioned ‘Cowper’s tame Hare’s [sic]’. The stated purpose of the volume was to raise funds for a memorial to Cowper in London.[v] Given that the engraving is designed as a proto-memorial, it suggests that anecdotes and illustrations of his hares had already come to be a prominent part of Cowper’s posthumous mythos as a poet, constructing him as variably gentle, sprightly, and wild.

Above all, Cowper’s hares were all about a sense of Cowper at home, at once domesticated and undomesticated. Cowper’s long autobiographical letter-essay, published in The Gentleman’s Magazine in June 1784, in which he described how he came by his pet hares as leverets and how he took them on as a project with a view to curing a bout of the severe depression to which he was subject provided a beguiling glimpse of a household in which the hares largely lived indoors in the hall and were admitted to the parlour after supper: ‘when the carpet afforded their feet a firm hold, they would frisk and bound and play a thousand gambols…’[vi] The essay evoked a Rousseauistic idyll of animal-human equality and sociability, caged birds, a cat, a spaniel, three hares, and a poet living together in mutual domesticated harmony because they had never been corrupted by human society:

‘I cannot conclude, Sir, without informing you that I have lately introduced a dog to his [Puss’s] acquaintance, a spaniel that had never seen a hare to a hare that had never seen a spaniel. I did it with great caution, but there was no real need of it. Puss discovered no token of fear, nor Marquis [Cowper’s spaniel] the least symptom of hostility. There is therefore, it should seem, no natural antipathy between dog and hare, but the pursuit of the one occasions the flight of the other, and the dog pursues because he is trained to it: they eat bread at the same time out of the same hand, and are in all respects sociable and friendly’.[vii]

In this essay and other short pieces, the hares came to mean sentimental sociability, rural retirement, and progressive domesticity; when Cowper published The Task in the following year, 1785, he figured himself as a hare.

All this goes far to explain the prominence of hares in posthumous figurations of Cowper, but does not explain the nineteenth-century celebrity of his spaniel Beau. None of Cowper’s hares were stuffed, but Beau was, and was subsequently displayed in a glass case. He ended up in Norfolk and mouldered away by the mid-19th century. The appearance of Beau on the frontispiece of The Rural Walks points up the difference between biography and this, one of the very earliest books devoted to creating walks that the poet’s admirers could follow while reciting pertinent passages from a book, in this instance, The Task. Wild hares imprisoned in a house may have been a suitable emblem for poetic domesticity; but an affectionate spaniel trained to walk at heel is a better figure for the reader who hopes to walk in the poet’s footsteps, and replicate his responses to the countryside. Those who did follow in Cowper’s footsteps in this way were occasionally driven to grumble at the unemphatic quality of the landscapes celebrated in The Task, and perhaps this is one reason why the stuffed spaniel has never been replaced. But while it is possible to imagine that the spaniel might not have been to modern taste, and would have been impossible to replace as such, given that this was sentimental rather than museal or sporting taxidermy, its significance in Cowper’s mythos – and therefore the Museum — has been overtaken comprehensively by that of the hare. The hare embodies a distinctive authorial mythos of personal vulnerability safely sequestered within an idyllic domesticity. There is a romantic statement at work here, a statement of the wildness, shyness, and only partially-tamed, partly domesticated nature of writer and writings that goes on fascinating visitors today.

To find out about 10 more items within the Museum that evoke Cowper ‘at home’, why not visit the online collection devoted to the Museum, ‘Romantic Dwelling’, curated by Nicola J Watson and presented by RÊVE (Romantic Europe: The Virtual Exhibition) www.euromanticism.org/virtual-exhibition/reve-the-collections/romantic-dwelling

[i] [J.S.S. i.e. John Storer], The Rural Walks of Cowper; displayed in a series of views near Olney, Bucks; with descriptive sketches, and a memoir of the poet’s life (London: Sherwood, Gilbert and Piper, c. 1825), frontispiece. This frontispiece does not appear in all editions/copies of this work.

[ii] Chesterton, ‘The Mystery of the Pageant’ . On this, see Michael Shallcross’ essay, in Restaging the Past: Historical Pageants, Culture and Society (2020), p. 81.

[iii] William Hayley, The Life, and Posthumous Writings of William Cowper esq… 3 vols, 2nd edn (Chichester: Printed by J Seagrave for J. Johnson, 1802) I, unpaginated.

[iv] Hayley (1802) I, p. 90.

[v] Hayley (1802) III, pp. 425-6.

[vi] ‘To Mr Urban,’ 28 May 1784, Letters (1981-1986) V, pp. 41, 42.

[vii] ‘To Mr Urban,’ 28 May 1784, Letters (1981-1986) V, p. 44.

Further Reading:

‘The Weather House’ ,Tony Seward, Cowper & Newton Bulletin

‘Cowper’s Tame Hares’, Nicola Durbridge, Cowper & Newton Museum publication

Rural walks of Cowper : displayed in a series of views near Olney, Bucks : representing the scenery exemplified in the poems

by Storer, James Sargant (online copy but without the Cowper and Beau frontispiece)

Nicola J Watson is Professor of English at The Open University. Her most recent book, The Author’s Effects: On the Writer’s House Museum (OUP, 2020) is available here

Nicola J Watson is Professor of English at The Open University. Her most recent book, The Author’s Effects: On the Writer’s House Museum (OUP, 2020) is available here