In 1900, the then newly opened Cowper Memorial Museum was given twelve Overseers of the Poor ledger books. They cover the period 1744 to 1820 and relate to the ‘Poor Laws’ in operation in Olney and the surrounding villages. Thanks to a very generous donation, nine of these books have been conserved and digitized, enabling us to discover more about life in Georgian Olney.

There have always been some people who had sufficient money and goods to live a reasonable life, and others who struggled to feed and house themselves. In Medieval times, the monasteries helped the poor but when Henry VIII seized all the Catholic Church buildings that source of support disappeared. Queen Elizabeth later instructed the Church of England to support the poor through a series of Poor Laws, which gave the local churches the power to raise taxes, used in part to support the poor of the parish.

How the Poor Laws Functioned

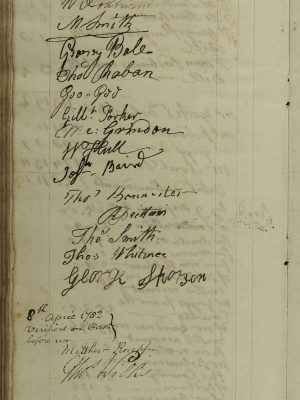

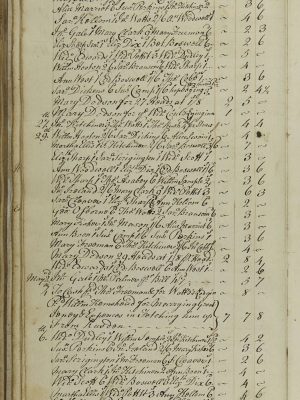

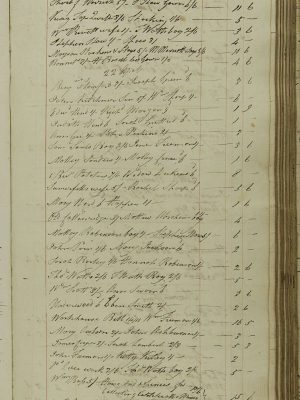

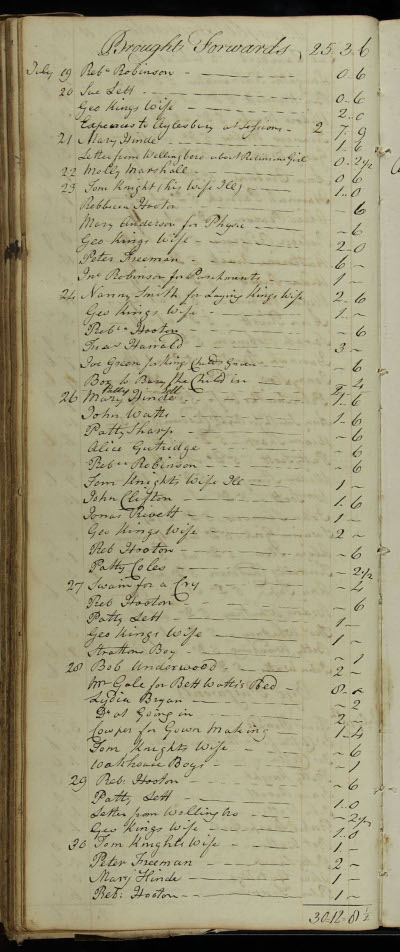

Every year, four of the better off residents would be appointed to collect the taxes and distribute the funds to the poor. They would hand out money on a weekly basis to a list of needy people, based on the number of adults and children in a household. Throughout this period, they would regularly help 60 to 70 households.

In 1749 the rate was six pence per week, but by 1800 it was a shilling.

At this time there were twelve pence in a shilling and twenty shillings in a pound, so one shilling was equivalent to five pence in decimal money.

In the eighteenth century poor relief was generally in the form of outdoor relief or the provision of money, food, clothing or other goods to paupers who continued living in their own cottages or relatives’ homes. Women often nursed the sick or undertook laundry work and men might repair parish roads.

The system of indoor relief in Poor Houses or Work Houses was principally intended for the sick, the elderly and orphans.

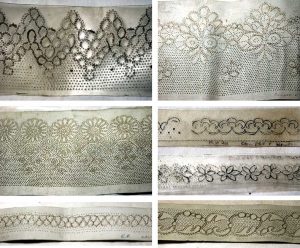

‘The Poor Rates in Olney are very high, owing to the great numbers of Lace-makers who are employed in the town, and who frequently become chargeable to the Parish’

From ‘A SURVEY VALUATION AND PLANS OF THE ESTATES OF THE RIGHT HONORABLE THE EARL OF DARTMOUTH SITUATE AT OLNEY, WARRINGTON AND BRADWELL ABBY IN THE COUNTY OF BUCKINGHAM’ Made in 1796 by the Thomas Bainbridge of Grays Inn London

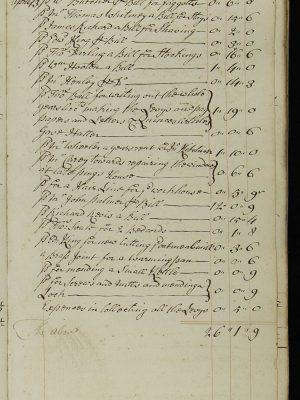

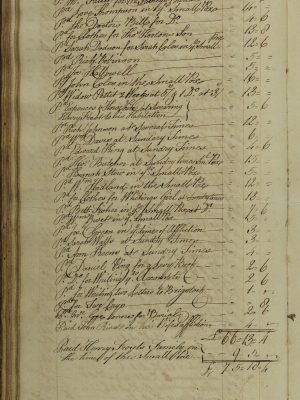

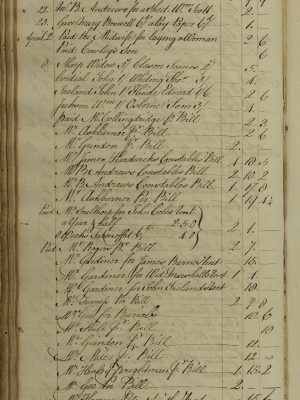

The Olney Overseers of the Poor levy and disbursement books show both the income and the expenditure of the vestry in considerable detail.

They show how funds were raised by monthly levies as well as by the sale of lace and produce from the Poor House. These funds were spent on a wide range of items, including the midwife, illness and injury, burials, supporting the poor in their own homes, the running costs of the Workhouse, the maintenance of roadways and properties in the town, and law and order. The funds were both raised and spent by a team of four Overseers who were elected to cover a year, each one covering three months. Below we have selected examples to show Poor Relief in action during this period.

Click on the images below for larger view

What Types of Support Were Available?

Investigate this yourself in the original source. The numbers in brackets below refer to the page sources above:

Rent

1747 – Sarah Boswell paid sixteen shillings rent for her tenant Richard Boswell.

1777 – John Wheeler paid one pound and ten shillings for a year’s rent for John Kitchener, and Mr Carey paid six shillings and six pence to repair the windows at the late Mr Ping’s house. (see image 786-1-0231)

Providing Clothing

1777 – Thomas Darling: paid sixteen shillings and six pence for stockings.

1782 – John Ireland’s son, David, given a waistcoat made up of hose costing five shillings and two pence, and a pair of shoes costing five shillings and six pence. (see image 786-2-0328)

Food and Other Household Needs

1777 – Mr Butcher’s bill for bread, flour and wood for Silas Chater and Ben Marriott’s families costing nineteen shillings and sixpence. (see image 786-2-0210)

Health

1756 – Paid for treacle to mix with physic for the children’s’ scald heads.

1766 – Dr Grindon* paid five shillings to cure J Rivet’s hand. (* Dr Grindon’s legers (1784 – 1793) are in the Museum collection)

1771 – Dr Aspray attended the poor people who were suffering smallpox in, receiving one pound sixteen shillings and sixpence in January, and nineteen pounds ten shillings and six pence in February; there were ten sufferers in May.

The records also tell us that the town must have had a pest house, used for persons afflicted with communicable diseases, because in 1777 Thomas Berrill was paid nine shillings and two pence for meat for the pest house.

1789 – Mr Cooke received one pound ten shillings to inoculate Gibson’s children and Widow Cobb received five shillings for dressing Ingram’s boy’s arm

Personal Items

1788 – Susan Cordial given a pair of spectacles at a cost of six pence. (see image 786-3-0284)

Funerals

Funerals were also often paid for. During the reign of Charles II, the wool trade had been declining so he ordered that bodies should be wrapped in wool to increase the demand for it. It was the job of the local clergyman to sign an affidavit to confirm that this had happened.

1771 – Mr Fabrey’s coffin cost seven shillings, Nathaniel Gee was paid one shilling and six pence to dig the grave, Mr Newton received one shilling for the affidavit. Mrs Fallett got four shillings and six pence for the burial, which would have been to provide refreshments at the wake. (see image 786-2-0072 )

For the burial of William Sharpe, they paid out six shillings and six pence for bread, cheese, butter, beer, laying out and the affidavit, with a further eight shillings for the coffin. (see image 786-2-0158)

Whose Responsibility?

The overseers would sometimes go to great lengths to keep their liabilities down. In 1765, at a cost of seven pounds seven shillings and eight pence, William Kemshead was brought from Rushden to marry “great Jenny”, so that he would support her and their child. (see image 786-1-0316)

Force was sometimes needed to bring people to face their responsibilities. This record for David Ireland shows Joseph Bond receiving two shillings and eight pence for victuals and drink for Thomas Mayes’s guard and man.

In 1806, the overseers even went to the expense of going to London and endeavouring to find T Green at a cost of one pound eleven shillings and six pence, plus twelve shillings and six pence for employing Bow Street officers. (see image 786-4-0309)

The Parish Poor House & the Work House

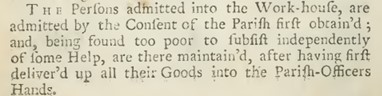

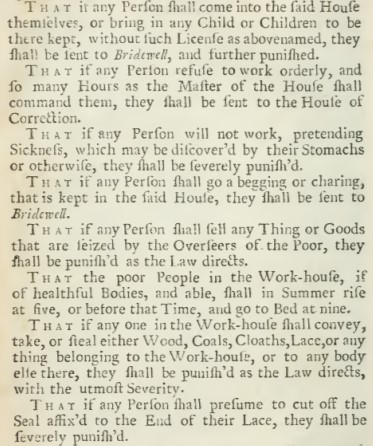

Olney as a town also had its own workhouse, where lace was made and vegetables cultivated in sufficient quantities to produce surpluses and then sold to offset the running costs. The inhabitants of the workhouse were those who were deemed unable to support themselves even if they were provided with Poor Relief. On entering the Workhouse, they had to hand over all their own possessions to the Parish Officers.

There are references to the ‘Great House’, Lord Dartmouth’s unused house in Olney, being used for this purpose. However, most sources refer us to a house(s) and yard on the site where Victoria Row (known locally as ‘Tory Row’) is now situated.

In 1763 it housed about twenty six adults, but the numbers fluctuated through our period between seven and twenty seven. In 1792 it was also housing around twenty five to thirty children.

The rules for this workhouse were published in the 1725 book ‘An Account of Several Work-houses for Employing and Maintaining the Poor: …’

‘To see that due Orders are kept in the Workhouse, a Master is provided to super intend it, whose Business is to keep the Poor to their Work, to see to the buying in and dressing the Provision, to give an Account of the Work done, and what is expended : This Master is maintain’d out of the Provision of the House, and a Salary allow’d him of 16 l, per Annum.

The Work which is done ordinarily in the House (the inhabitants being most of them old) comes now to about I 5 s. a Week, which is given to the Parish Officers, as a Part of what is to contribute to the

maintaining them.’

After the Poor Law Act of 1834, parish workhouses were closed and large union workhouses were built in the larger towns. Newport Pagnell Poor Law Union was formed in 1835 and served the local area. Although the Commissioners for Olney and the surrounding villages had sought for an Olney Union to be created, they were not successful.

Records for the winding up of the Olney Parish Workhouse, including the selling of the house and land, can be found at the National Archive and are free to download from their website.

Of the nine books which have been conserved and digitised, 78,000 entries in them have been entered into a searchable database (excel) We stock a booklet and a memory stick containing all the images and the database; the pack of these two items is for sale for £10 in the Museum or by post. The nine books have been digitised thanks to a generous monetary donation to the museum: another three books are awaiting funding to make them available to researchers.

FURTHER READING

The National Archives discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/

‘An Account of Several Work-houses for Employing and Maintaining the Poor: …’: Digital edition