Surprisingly, William Cowper owned and operated an electric shock machine, and used it to treat Mrs Unwin after her second stroke in 1792. It consisted of a large glass cylinder, a wooden disc and turning handle, a Leyden Jar, a ferocious-looking metal tube with spikes and knobs, as well as other bits and pieces. The apparatus – this medley of glass, metal and wood – was installed at The Lodge, Weston Underwood by William Hayley, a poet and admirer of Cowper. Following the stroke Mrs Unwin, Cowper’s companion for many years at Olney and then at Weston, was ‘in such a disorder’, as he put it, ‘and her amendment so slow’, that he agreed to try out this latest medical ‘cure-all’.

The electrifying machine: its parts and operation

The glass cylinder

Where to begin?! There are various glass jars and tubes in our display cabinet, but perhaps the best place to start is with the most striking object: the large glass cylinder supported horizontally on a wooden spindle. The glass body of the cylinder has been broken, or badly cracked, at some time but has been rather attractively mended with white tape wound several times round its circumference. It looks rather as if the glass is decoratively striped rather than held together with lengths of tape. This cylinder was a crucial, as well as impressive, part of the machine as it was the source of the static electricity needed for the ‘shock’ part of the medical treatment. To make static electricity we need friction and it may be helpful to be reminded, very briefly, why.

Electricity may be defined as the flow of electrons between atoms. Electrons are negatively charged particles on the outer shell of atoms and they are moveable. Some materials – glass is a good example – hold onto their electrons tightly; these materials make good insulators, as electrons do not move through them easily. Other materials, such as metal, hold on to their electrons only loosely, so these materials make good conductors as electrons can travel through with little difficulty.

The friction part of this story comes into play if we want to make electrons move from one place to another so as, for example, to ‘charge an object up’, an object like our glass cylinder. If we rub two different insulating materials together, electrons may be transferred from one surface to the other. It is not the rubbing itself, but the increased brief contact through rubbing that builds up a static charge.

In the context of our machine, friction would have been achieved by spinning the cylinder and rubbing it as it revolved. The cylinder was turned with a wooden handle attached to a wooden disc; we can see both the handle and disc lying in the case near each other. They would normally be screwed to the bolt we can see at one end of the cylinder.

To create the necessary friction, a silk or leather pad, stuffed with hair, was held against the glass as it spun, thus rubbing its surface and transferring electrons from the glass to the silk. (The so-called ‘triboelectric series’ ranks materials in order of their ability to hold on to, or give up, electrons.) This activity generated a positive electric charge which accumulated and was held on the glass until it had somewhere to go. So, supposing now that we have charged up the glass cylinder with static electricity, what can we do with it?

The metal conductor

This is where the metal cylinder in the display case comes in. The fearsome-looking metal tube – it has one pronged and one knobbed end – was called ‘the prime conductor’. It was the main channel through which electrostatic energy was passed. The three-pronged end of the conducting tube (it looks a bit like a toasting fork) was positioned about one centimetre from the glass cylinder and ‘sparks would fly’ as electricity jumped between the two dissimilar materials – the glass and copper surfaces.

We might wonder whether the knobs and teeth at either end of this vicious – looking beast weren’t really more about ‘show’ – terrifying visual confirmation of the power of the apparatus – than necessary terminals. However, a knob or metal point at the end of a cylinder like this would have helped to draw a flow of electrostatic energy towards it.

Leyden jars

Amongst the equipment on display there are also two ‘Leyden jars’ – an important invention for storing an electric charge. The Leyden jar (or Leyden bottle) was invented in 1746 by a professor of physics at Leiden University, Pieter van Musschenbroek (at least, his is the name most commonly invoked for these jars). In fact the year before, quite independently and coincidentally, the same device was concocted by a German cleric, Ewald von Kleist, and it is sometimes called ‘Kleist’s bottle’. The jars are a compact means of storing static electricity.

A Leyden jar of this period is pretty straightforward to describe. It is a glass jar, lined inside and out with metal, and topped with a tightly fitting lid, usually of cork. The lid is pierced to hold a protruding length of metal – a thin rod or wire – usually with a knob on top. This knobbed metal rod continues down inside the bottle so as to touch the interior metal lining; it is this contact that enables the jar to be charged. The bottle is filled by transferring accumulated static electricity onto the metal conducting rod; it can remain stored in the bottle until discharged by touch. There is a standard version of a Leyden bottle in the display case (above) and one other rather narrower storage bottle (lying on its side in the second picture). The fatter bottle with the round metal knob protruding from the cork is more typical.

Directing tools

Also on display is a glass tube – a handle in effect – with a wooden fork at one end and a large round knob at the other. This probably belonged to another important piece of missing equipment – the so-called ‘directing wires’. These wires conducted the electric discharge from the prime conductor or Leyden jar to the appropriate part of a patient’s body. They could be directed by pointing, or they might touch. The operator of the machine held the directing wires with an insulated glass handle much like the one we can see here. In a moment we’ll look in more detail at the advice Cowper followed relating to ‘dosage’.

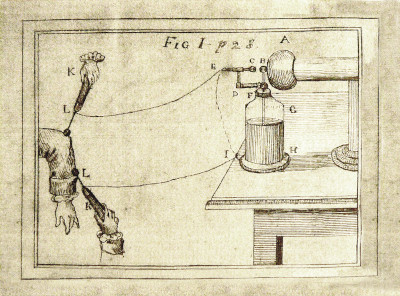

To complete the medical side of the operation, the administration of a small electric shock, a patient needed to sit or stand near the machine (there were such things as ‘insulating chairs’ but they were not always thought necessary) and be connected in some way with the electric discharge. Usually, patient and conductor were linked by a wire which had a piece of wood tied to one end and was attached to the prime conductor by the other, as in the illustration here (taken from a 1780 treatise by Tiberius Cavallo, which we will come to later).

Wooden ‘points’ came in different shapes and sizes and were made of soft, not hard wood. They would be applied to the troublesome part of the body – whether eyes, teeth, limbs or ‘innards’ – and the static energy thus transferred to it Sometimes the wooden point would merely be waved near the patient rather than touching them; sometimes the wire alone would be used: such variations depended on the strength of electric energy needed, or thought desirable. Much that was ‘desirable’ was achieved through trial and error, as we shall shortly see.

But before we find out how the patient, Mrs Unwin, responded to this treatment it might be interesting to learn how Cowper got hold of the electric machine in the first place.

Finding a machine: the social context

Electric machines really do seem to have been ‘all the rage’ in mid-eighteenth century England. There was clearly a buzz of excitement related to the research, experiments and debates amongst electricians, medical men and ‘natural philosophers’ (as scientists were known at this period) and this noisy energy seems to have filtered through to the general populace.

Men with ‘big names’, enthusiasts such as Erasmus Darwin (Charles’s grandfather and himself a scientist as well as a physician and experimenter with electricity) led the way. Other progressive thinkers such as Matthew Boulton and Josiah Wedgwood – famed industrial and manufacturing entrepreneurs – believed, along with Darwin, that electric energy appropriately harnessed would lead to social improvement and political reform. They, together with three of the most important electricians of the day – Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Priestley and Abraham Bennet – created a field of force that inspired a wealth of enquiry and experimentation.

Electricity became the fashionable wonder of the day. Apparently there was even a vogue for salon experiments, where electrostatic machines became a preferred toy for amusement. Many in ‘society’ wanted to experience an electric shock, and the ‘electric kiss’ is said to have offered a particular thrill.

Amongst its medical applications we know that one of Wedgwood’s daughters was treated by Darwin with static electricity for paralysis and convulsions, and he also applied it to the stomach of a patient suffering from tapeworms. (The latter were notoriously hard to get rid of and could remain an active problem even when dosed with ‘boiling water, gin and whiskey’. It was thought that the shocks may have killed the worms in the Darwin case – something did – but the medical report reveals that really no-one was too sure which ‘bit’ of the treatment delivered the final blow.) Darwin also treated people with jaundice, gallstones, throat complaints, cramps, numb limbs and bad eyes (Georgiana, the Duchess of Devonshire in the latter case). Meanwhile John Wesley promoted electric medical treatments because they were relatively cheap and so, he hoped, might be used to help poorer members of society.

Given such widespread interest in electricity generally and in electrostatic machines in particular, it is perhaps less surprising to learn that there was a machine available to be borrowed in the small village of Weston Underwood. Cowper’s friend Hayley had enthusiastically recommended electrical treatment for Mrs Unwin, and Hayley it was who tracked down a machine in the house of the aptly named Mr Socket at Weston and had it installed in Cowper’s home. (Thomas Socket had a stationer’s and bookseller’s business in London but had been recently been declared bankrupt.) Hayley even arranged for Mr Socket’s young son Tom to come in and turn the cylinder so as to generate the electric energy, while he or Cowper administered it to Mrs Unwin (the machine needed two operators.)

John Newton’s use of an electrical machine

Before turning to Mrs Unwin’s treatment, it is interesting to note that, encouraged by John Wesley, John Newton had purchased just such a machine many years before. On 13 April 1761 he wrote in his diary,

‘I am about undertaking to keep an electrical machine for the use of the poor as I find this wonderful phenomenon has an uncommon effect in nervous cases and generally in all obstructions.’

At this time he regularly visited one Mrs B, ‘a lady much distressed in mind’, apparently bringing the machine with him, but it’s not known if she derived any benefit from it.

Shortly after taking up his full-time ministry in Olney in 1764, a further diary entry records that

‘A part of my time three afternoons in the week is now devoted to the Electrical Machine. I have generally six or more patients, and hope it has been already in some measure useful.’

Newton to Alexander Clunie, Olney, 4 March 1766

‘I beg you likewise to tell Mr Madan that my [electrical] machine was made by Mr Reid, cabinet maker in Compton Street, Soho.’

He continued to use it for the benefit of his parishioners – with the added advantage, in at least one instance, that by its means he attracted a new member to his flock.

‘A young woman that came three or four weeks ago from Sherington to attend the machine for the relief of a rheumatic disorder, has thereby had the opportunity of attending the church…She goes home next week, but is loath to leave us.’

Ten years later, following Cowper’s serious depressive episode of 1773-4, Newton persuaded him to try the machine, to see if it could in any way relieve his condition.

‘A thought of the machine with respect to my dear friend struck me the other morning as we were walking together. Prevailed on him to let me make experiment of it today. But could not observe any sensible [obvious] effect’

It is odd that there is no mention of this experiment in Cowper’s letters, when the idea of using an electrical machine on Mrs Unwin was being mooted, but perhaps it belonged to a period of his life that he did not wish to recall.

The patient

In 1792, Mrs. Unwin had her second stroke. Here is Cowper describing the first, which struck her down at the end of 1791.

‘On Saturday last, while I was at my desk near the window, and Mrs Unwin at the fireside opposite to it, I heard her suddenly exclaim, ‘Oh! Mr Cowper, don’t let me fall!’ I turned and saw her actually falling, together with the chair, and started to her side just in time to prevent her. She was seized with a violent giddiness, which lasted, though with some abatement, the whole day, and was attended too with some other most alarming symptoms. At present however she is released from the vertigo, and seems in all respects better, except that she is so enfeebled as to be unable to quit her bed for more than an hour in a day.’

This was written on 21 December. But by February, apparently, she was able to ‘take 2 or 3 turns in the walk’, though her recovery seemed to Cowper so slow that ‘the difference made by a whole week is hardly perceptible’.

Then, in May, Mrs Unwin was ‘again attacked by the same disorder …’. She lost the use of much of her right side – her hand and foot sometimes quite useless – and her speech badly affected and becoming less distinct as the day drew on. It was at this point that the electric machine was sought and installed, and seems to have been immediately effective: ‘we think it has been of material service’, says Cowper. But clearly this second stroke has done quite a bit of damage, for just four days later he writes,

‘I have been sadly desponding all this morning and had a terrible night. Her right side is indeed so perfectly disabled that I have hardly any hope that she can ever be herself again.’

But by June he is again more positive. He writes to Hayley,

‘The stronger she grows the faster she gathers strength…Yesterday she moved into the electrifying room with very little help from her supporters, and carried herself more erect than at any time before. She seems however to have a better opinion of your spark-eliciting faculties than mine, and was once or twice so riotous that I had much ado to manage her. She even had the hardiness to tell me of your superior skill, and when the snaps were fast and frequent to say, Hayley would not do thus if HE were here.’

It’s interesting to learn from a couple of Cowper’s letters of Mrs Unwin’s preferred diagnosis of her problem. In her view this was not a stroke at all:

‘She is persuaded that there is nothing paralytic in her disorder, but that it is a complex case consisting entirely of bile, spasm and rheumatism…’

It is, in her view,

‘a nervous rheumatism accompanied by those spasms to which she has so many years been subject. Formerly they affected her bosom, and now she judges them to be the same that have seized her limbs.’

Cowper on the other hand thought her ‘dreadfully alarming’ illness was directly linked to an accident that occurred just outside their house. It befell a local man called John Britain who was delivering a wagon of coals to their gate. He

‘…was first squeezed between the wheel and the post, and then thrown under the wheel or rather right before it on his back, so that had the horses moved another step he must have been killed infallibly. She was in the servants’ hall when this happened and consequently within hearing of the outcry and…being immediately told that he was much hurt and how narrowly he escaped, she was so much agitated in her spirits she never recovered the effects of that emotion, and three days after was struck with this illness. Such have always been the effects of surprise and terrour upon her; she endures them for a few days as if she would get the better of them and then sinks under them.’

Mrs Unwin also had views about her treatment. Part of her preferred remedy was to have ‘Steer’s Opodeldoc’ rubbed into her back. She asked for an extra supply of this and it was apparently ‘of prodigious use to her’. (Steer’s medicament was a soft ointment composed of 3 ounces of soap dissolved in a pint of alcohol, an ounce of camphor and a drop of each of two oils – origanum and rosemary It claimed to relieve sprains and bruises as well as rheumatism.) At the same time the poor woman also appealed to her doctor for a laxative (or ‘aperient electuary’ as Cowper calls it); so there was evidently quite a variety of inputs into her condition and it is hard to unravel what might have been achieving what. Still, Cowper remains sure that the electric machine is performing an important role:

‘Her recovery, so far as it may be called one at present, has been effected chiefly I believe by electrical operations…we administer this remedy every day, and every day seem to perceive the good effects of it.’

And by the middle of June, just three weeks after the attack, she is able

‘to speak articulately, especially in the morning, and to move from one room to another with very little support…’

While by the last week of June she is so much improved that

‘We have both left off all Narcotics. She sleeps without her paregoric, and I without Laudanum.’

(The ‘paregoric’ was a tincture of opium.) She is also walking better:

‘…she walked yesterday, at two journeys, twenty times the length of the orchard-gravel…but these feats she performs between me and Sam…for she has rather a tottering step, and should she stumble it would hardly be in the power of one to prevent her falling. She walks in my shoes too, her ankle being so much weaken’d by this illness that in her own it cannot support her…’

Going by the book

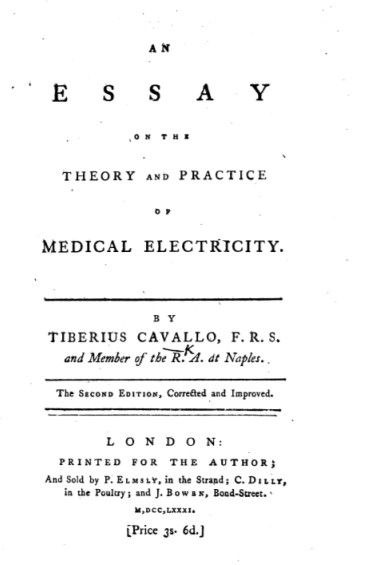

We referred earlier to the 1780 treatise on electrical treatment by Tiberius Cavallo, FRS (1749-1809). Cavallo was an Italian, born in Naples, who came to London in 1771. A physicist and natural philosopher, he invented and improved many scientific instruments and was particularly active in the field of electricity. Our machine – and there were many variations along its lines – looks very much like a ‘Cavallo Machine’. In any event it was the advice in his Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Medical Electricity that Cowper, on the recommendation of his apothecary, studied and followed.

The reference is helpful as Cavallo’s work provides detailed recommendations and explanations about best practice (along with evidence from case studies) as well as some illuminating illustrations showing the set-up of the apparatus. He establishes two main operating rules.

First, the operator

‘…should begin to administer to his patients the very smallest degree of electric power which he ought to continue for a few days, so as to observe whether it provides any good effect, which if it fails to do, he should then increase the strength of electricity; and so proceed gradually till he finds the effectual method which he should follow…till the patient is entirely cured. In short the operator should always use the smallest degree of electric power that is sufficient for the purpose.’

Cavallo has already explained that the stream of energy can be easily controlled and increased by using in succession

‘a metal point, then a wooden point, then small sparks, – stronger sparks, and lastly small shocks…and every one of these methods may be increased or diminished considerably by…turning the wheel of the machine swifter or slower…the sparks may also be made stronger or weaker, by taking them at a greater or less distance.’

Cavallo’s second rule was that a patient should never be administered more ‘electrization…than he or she could conveniently suffer.’ Less is clearly more; and here he is again pressing the point:

‘It should be attentively observed to employ the smallest force of electricity, that is sufficient to remove or alleviate any disorder, thus shocks should never be used when the cure may be effected by sparks; the sparks should be avoided when the required effect can be obtained by only drawing the fluid with a wooden point; and even this last treatment ought to be omitted, when the fluid drawn by means of a metal point may be thought sufficient.’

And here is Cavallo again describing different strengths of electric charge; as ever, the range of flowing and breezy imagery he uses to capture distinctions is precise:

‘The electric fluid issuing from the wooden point has a power which is intermediate between that of the stream proceeding from a metal point, and the power of the sparks. This stream consists of a vast number of exceedingly small sparks, accompanied with a little wind, which gently irritates the part electrified and gives a warmth which proves very agreeable to the patients.’

Anyway – Cowper clearly got the message, as he reported to Hayley that:

‘This author I find recommends gentle sparks and the fluid breathed from a wooden point, much rather than smarter sparks or shocks. I have accordingly treated her in this manner these 3 days past and she thinks herself more benefited than when I gave her more.’

Cowper was still delivering daily doses in July 1793:

‘I am just going to electrify Mrs. Unwin, which done, I must take a short walk and dine.’

And he continued to have these ‘sparkling days’ right through to the end of that year:

‘When Mrs Unwin was taken ill two years ago, we borrowed of Mr Socket, our neighbour then, an electrifying machine, which she has used ever since and is not now well enough to spare. Mr. Socket, I understand, is very much indisposed, and having formerly received benefit by the use of electricity is desirous to try it again. We mean therefore to purchase their machine by furnishing them with another in its stead …’

Mrs. Unwin died in 1796, the year after she and Cowper had left Weston for Norfolk, there to be looked after for the remainder of their lives by the family of Cowper’s kindly young cousin, Johnny Johnson.

Further reading

Cavallo, Tiberius, Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Medical Electricity, 1780

Cavallo, Tiberius, An Essay on the Theory and Practice of Medical Electricity, 1781

King, James, and Ryskamp, Charles (eds.), The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 5 vols, 1979-86). All quotations from Cowper’s letters are taken from this edition.

Rouse, Marylynn (ed.), John Newton’s Diary: 1764 (an annotated transcription), The John Newton Project, 2020. Copies available from www.johnnewton.org

Watkins, Francis, A Particular Account of the Electrical Experiments…to which is annexed The Description of a compleat Electrical Machine, and its Apparatus, with the Way of using it, 1747